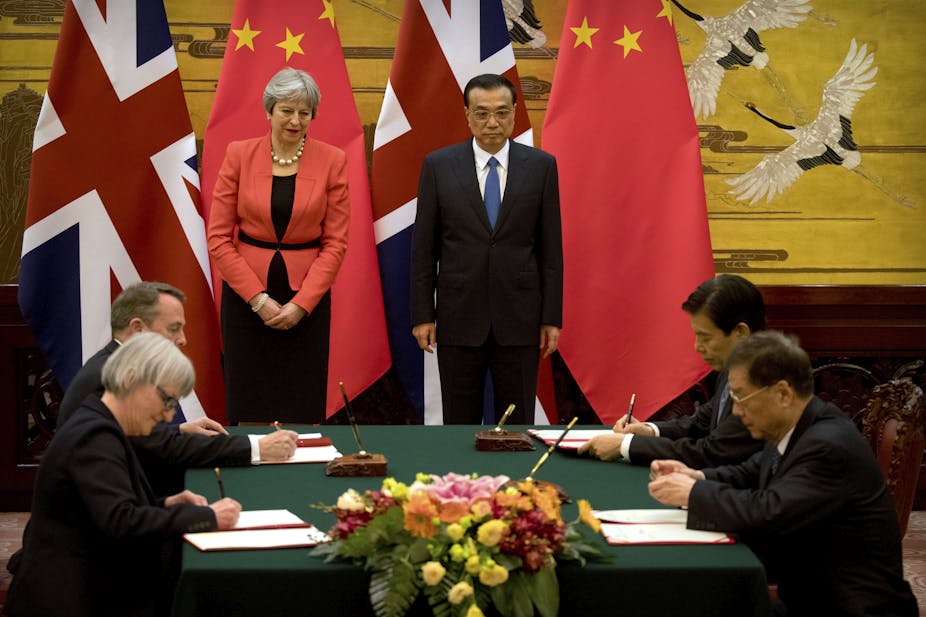

British prime minister, Theresa May’s visit to China has been portrayed as an opportunity to set the groundwork for a free trade agreement between the two nations. In this endeavour, she hopes to achieve something that has long eluded the EU.

The UK’s historic record as an advocate of free trade is often cited by advocates of a hard Brexit as an alternative to the growth-constraining regulations and protectionism of the EU. The international trade secretary, Liam Fox has gone so far as to argue that the UK’s example and evangelism for “rules-based free trade” (free trade under WTO rules) will play an important role in global poverty reduction post-Brexit.

But this argument is based on nostalgia for a system where free and fair trade represented a cornerstone of Britain’s foreign policy. It is nostalgic because such a system, which had its origins in colonies and treaty ports, was neither free nor based on fair rules. It’s a fallacy that provides – at best – some comfort against the uncertainty of Brexit. At worst, it evokes memories among many countries, including China, of an era when trade was used to exacerbate exploitation rather than alleviate poverty.

The arguments that rules-based free trade reduces poverty do not stand up to scrutiny. Not only are they divorced from the history of the colonial trade system, they are also inconsistent with the way in which China lifted some 700m citizens out of absolute poverty.

Much of China’s early and rapid reduction in absolute poverty had little or no relationship to trade reforms. Instead, the achievement can be traced to the acceleration of urbanisation, the transfer of rural agricultural labour to urban manufacturing, transfer payments, and targeted poverty reduction schemes. This is significant as much of the reduction in poverty attributed to rules-based trade has come from China’s domestic economic reforms, which sought to manage and control the supply of foreign investment.

Plus, the assertion that a “protectionist” EU has constrained the UK’s ability to form free trade agreements with its “natural” trade partners in the Commonwealth has been shown to be inconsistent. The EU incorporated many of these countries into its system trade preferences after the UK joined its precursor, the EEC.

Championing nostalgia

The colonial trade system was neither built on free trade nor liberal economic policy. Instead it functioned on the basis of strict currency controls, centralised planning and unbalanced economic power, which favoured the colonial power.

The early system of colonial money was underpinned by scarcity of supply and control over its colonies’ balance of payments situation. Britain’s trade policies ensured that early American colonies were perpetually short of cash – such that they often resorted to barter. And any coins that they earned from trade with other countries were normally lost once they imported finished goods from Britain.

The now defunct sterling area enforced strict exchange controls across virtually all of Britain’s colonial territories, the Commonwealth, and a number of other states such as Ireland. Colonies such as Hong Kong were subject to regulations when it joined the sterling area. This meant that it was required to exert careful control over its currency and share information on sterling supply within the sterling area. This reporting also extended to non-sterling area exports and was extremely cumbersome. For example, large spending by companies would first need to be cleared by the local currency board.

The system only functioned because, unlike sovereign states, crown colonies did not have independent monetary policies. A large devaluation of sterling in 1967 and the ending of the Bretton Woods global system of monetary management in 1971 effectively put an end to its function.

But participation in the sterling area via Hong Kong’s free market also offered an early lesson to the People’s Republic of China on the value of monetary policy independence. The lesson of this colonial system of currency was one of enforced planning and austerity, which initially benefited the UK but later became far too costly to maintain.

Misplaced sentiments

There are undoubtedly positive ways in which a post-Brexit UK can contribute to international trade and development. But references to a now defunct colonial system based on unequal economic power should not be one of them.

Ireland’s importance in phase one of the Brexit negotiations should provide a strong warning to UK negotiators that the influence and position of its former colonies and members of the sterling area has vastly changed. And the international economy is also now very different from that of the colonial era.

In reflecting this, UK negotiators could show a similar approach in promoting a progressive vision of the UK post-Brexit. This could involve championing tolerance, migrant rights, working conditions, more diverse education curricula, poverty reduction and technologies in the area of climate change mitigation.

Perhaps the biggest irony is that the UK’s best prospects for a favourable trade agreement with China, a strong currency and rules-based trade are to be found by remaining within the EU. The EU has long been reluctant to grant China market economy status until it can demonstrate that Chinese product prices reflect their market value. More recently, it has sought to develop a more cohesive approach to Chinese investment in EU countries.

In holding China to rules-based trade, the EU is therefore following the very approach that those in favour of Brexit appear to be advocating. And, as one of China’s biggest export markets, has far more clout to shape these rules.