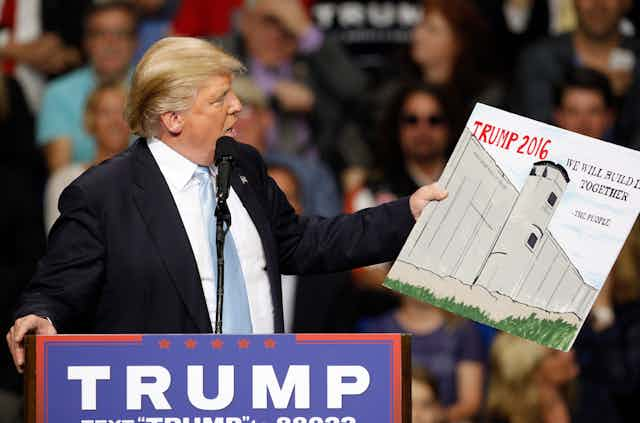

Donald Trump tweeted on Jan. 6 that “any money spent on building the Great Wall (for the sake of speed), will be paid back by Mexico later.”

Feasibility aside, this policy reflects a common belief among governments that countries should be walled, and that walls solve problems of migration and trade.

The Economist reports that 40 countries have built fences since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Thirty of these were built since 9/11; 15 were built in 2015.

The United States already has about 650 miles of wall along the border with Mexico. Hungary built a wall on the Serbian border in 2015, and is erecting barriers on its borders with Romania and Croatia to hinder the entrance of refugees. Spain – an important link in Europe’s southern border – built fences in its enclaves of Ceuta and in Melilla (northern Morocco) to thwart African immigration and smuggling.

My research focuses on why countries build legal and physical walls, especially in the Americas. The logic of walls – creating a spatial separation between people – predates the current craze. It’s part of a broader logic of nation-building that humans have used for over three centuries.

This strategy is politically appealing for its simplicity, but it misunderstands the problems of globalization and migration it aims to address. Building walls has rarely has achieved its intended effect, and may result in wasted resources and lost opportunities for the United States.

Logic behind walls

People in countries like the United States and Britain are uneasy about what they perceive as falling economic fortunes, and outsiders who threaten a way of life. Erecting paper or concrete walls to protect the national economy, jobs and culture is a strategy that has strong appeal. British Prime Minister Theresa May recently referred to the Brexit plan as a way to regain control of Britain’s borders from Europe, and to “build a stronger Britain.”

In U.S. history, building paper and concrete walls resulted in episodes that today are widely viewed by historians as inconsistent with our better democratic angels.

Among the first paper, or legal, walls erected in the U.S. were the Chinese Exclusion Acts, which limited the entry of Asian immigrants, as well as their eligibility for citizenship, beginning in 1882. What the late political scientist Aristide Zolberg called “The Great Wall against China” did not come down until 1943, and did only then because the U.S. needed China’s support in the war against fascism.

For 220 years, the U.S. discriminated against prospective immigrants and citizens on the basis of race. Although the United States was among the first countries to implement this strategy of excluding by race, all other countries in the Americas, Australia, New Zealand and southern Africa had similar laws and policies. In the U.S., this approach led to policies such as Chinese exclusions, the Nationality Quotas Act (which selected immigrants by ethno-racial origins), Japanese internment and closing doors to Jewish refugees fleeing murderous Nazi persecution.

Most countries used discrimination by origin to build their nation. It allowed political elites to choose which immigrants were suitable as workers, or as citizens. For example, in the U.S., Chinese immigrants were seen as suitable as workers who did dirty, demeaning and dangerous jobs, but not as full members of the nation.

Rise and fall of walls

My work with David FitzGerald describes how blatant discrimination by race in immigration and nationality law eventually came to an end in the Americas, including in the United States. This marked a decline in wall-building policy, though not of the underlying racism which surfaced in other policy areas.

The United States and other powerful, primarily white countries needed the support of countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa to wage wars against fascism, and later communism. The U.S. and its allies could not easily ask for support from the countries whose citizens they excluded on racial grounds.

Reluctantly, the U.S. and Canada ended their overtly discriminatory immigration and nationality laws in the 1960s – much later than other countries in the Americas. The fall of paper walls against particular groups resulted in a dramatic demographic transformation. In the 1950s, immigrants to the United States were 90 percent European and 3 percent Asian. By 2011, 48 percent were Asian and 13 percent were European.

The face of the nation was transformed, and “Americans” confronted questions about who was a full member. Was it those who belonged to a particular ethnoracial group? Or, was it those who subscribed to civic ideals of democracy?

The demographic changes that have happened since the demise of the Nationality Quotas Act in 1965 have again raised these questions among whites in the political mainstream. Immigrants are settling in “new destinations” – areas primarily in the South and Midwest that had experienced little migration until the 1990s. Calls to revive the logic of walls have become louder in those areas.

No easy fix

Building a wall does not address the complexities of unauthorized migration, or the economic woes of America’s middle class.

For instance, as many as half of unauthorized immigrants in the United States are people who overstay their visas, not border crossers. Barriers also result in more deaths because people try to cross the border at the most inhospitable and unwalled places. The barriers in place now have generated billions of dollars of federal expenditures for border security and investment.

Working- and middle-class Americans are also feeling a vague unease about their place in the economy. Rhetoric that identifies specific culprits – immigrants and international trade – is very appealing. So are simple, concrete solutions.

But walls to limit mobility or trade are too simple a solution to a complex problem. Today’s economies are more linked by exchanges of data, goods and services between countries than at any time in the past. Workers have also moved between countries, even if with greater regulation than in the past.

The effects of global income inequality have been felt differently among groups. Economist Branko Milanovic’s research shows that during the most intense period of globalization, from 1988 to 2008, people in Asia and in the top 1 percent of global earners experienced the highest real income growth. Meanwhile, people in the lower- and middle-income strata in Western Europe, North America and Oceania experienced no growth.

The demographic shifts described, the perceived loss of political advantages among whites and stagnant incomes among working- and middle-class people in the United States are hard realities. No wall can change these facts.

Most importantly, walling the world distracts citizens and policymakers from complex problems. Extreme economic inequality, global conflict and environmental decline surpass the borders and capacities of any single country.