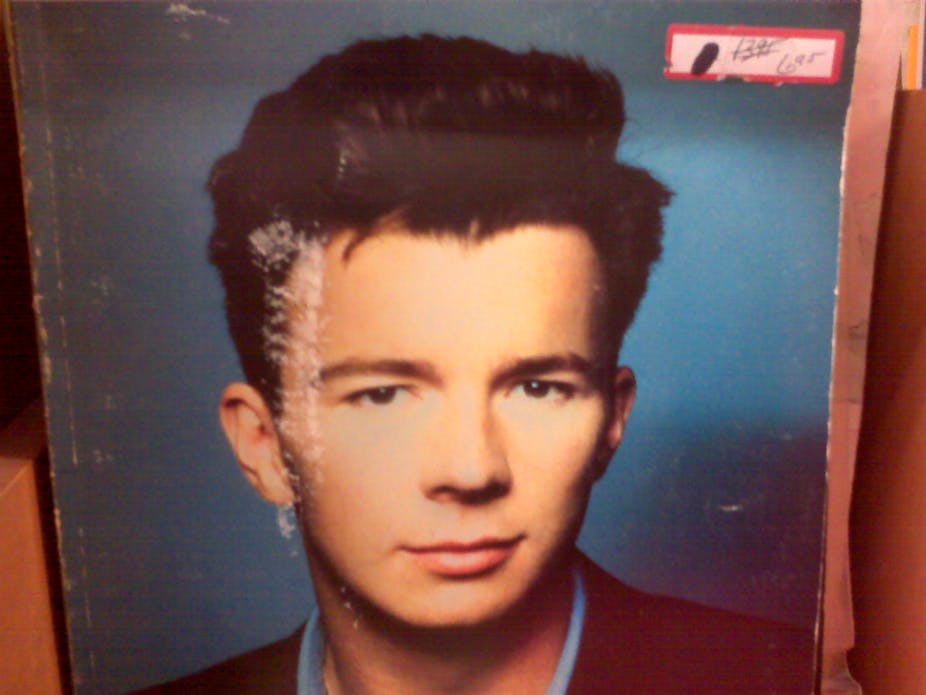

Rick Astley, 80s pop singer and unlikely king of internet memes, is dead. Or at least the most persistent song in his catalogue is. Or at least its most popular unofficial YouTube upload is. Or at least it was, for a few hours, most recently in July 2014 but before that in 2012 and again in 2010. And in the exaggerated rumours of its death are lessons on intellectual property, internet culture, and what resonates in the ephemeral swirl of the socially-mediated web.

Of course, when people talk about Rick Astley in the context of internet memes, they’re usually referring to the phenomenon known as Rickrolling, which emerged on infamous trolling hotspot 4chan in 2007. The name is derived from an earlier 4chan meme known as Duckrolling, in which someone expecting to see a specific link or image is instead redirected to a picture of a duck on wheels. On May 15, 2007, user cotter548 posted Rick Astley’s 1987 hit “Never Gonna Give You Up” to YouTube with the title “RickRoll’d”. It was linked to 4chan, and an online icon was born.

The initial success of Rickroll (and Duckroll before it) was due to the long-popular practice of providing an obscured URL promising some interesting, titillating, or (in trolling circles) disturbing video or image, and then redirecting one’s target to something completely unrelated, the weirder the better – all the better to troll you with. This behaviour first gained popularity on the various shock sites of the late 1990s and early 2000s, including Rotten, Stile Project, the Gen May forums, and could be extraordinarily disturbing.

Rickroll was safer and altogether more accessible. And even though the meme was subcultural, its success was also contingent on the video being kept active by those who owned the rights to it. That meant Google-owned YouTube and Sony-owned RCA Records had to be on board.

And it certainly paid off. The original Rickroll has now attracted more than 70 million views (its official Vevo counterpart has 84 million). But the attention hasn’t always been positive. The original video has been taken down from YouTube at least three times. On February 24, 2010, it was removed for a few hours – long enough to get press – before Google reinstated it. The company said the takedown was a mistake that happened when the video was inappropriately flagged as a violation.

On May 23, 2012, another day passed without Rickroll – apparently stemming from a request by the anti-virus AVG Industries – before Google quietly resurrected it. And on July 17, it mysteriously went silent again, and – with just as much apparent mystery – never really went anywhere at all.

Rickroll thus serves as a valuable reminder of the ephemerality of internet culture, and the eagerness with which many have gathered around, helped curate, and variously appropriated cultural content online. These appropriations are often premised on a precarious arrangement between participants who create, circulate, and transform cultural artifacts and the corporate entities that own source texts. “Never Gonna Give You Up” is a commercial product, after all. It’s the intellectual property of Sony, housed on YouTube, at the pleasure of Google.

The spirited, buzzing, mass participants that found Astley resonant and made him the heart of an ever-expanding cultural joke do their work – to borrow a term from scholar Michel de Certeau – as “poachers”. They “make due” with texts not narrowly their own. Their creativity constitutes vibrant digital folklore. Needless to say, folklore stitched together across hyperlinks exists only as long as those hyperlinks survive. But it’s folklore still. Lee Knutilla argues that seemingly simple bait-and-switches, most conspicuously embodied in Rickrolling, have helped establish a complex community on 4chan’s ephemeral boards.

As RickRolling and other memes have spiralled out from their subcultural origins, more and more participants are able to poach meaning from them. With each Rickroll, Astley’s boyish smile and earnest dancing are lifted from their 80s origins and made fresh by ironic reuse and misuse. Through such appropriation, the video has become enmeshed in a family of internet traditions, and has handily moved beyond its subcultural roots. It has, in other words, become bigger than any broken hyperlink.

Rickroll’s legacy is one of transcendence: of platform, of community, of standard business practices. It has even shored up Astley’s legacy. In a 2010 TEDTalk, 4chan’s founder, Christopher “moot” Poole, directly credits Rickrolling for “Rick Astley’s rebirth” as a pop culture touchstone.

Clean cut

Beyond that, Rickrolling has provided a family-friendly inroad for talking about some of the most hardcore weirdness on the web. The cultural soup from which the meme emerged is often too gruesome or explicit to reproduce in TEDTalks, Siri inquiries, and Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parades. Rickrolling is a trolling practice you can explain to the uninitiated or discuss around more polite dinner tables. It’s a safe subversion, an endearing –- if annoying –- “Aw, ya got me”. It’s Tom Sawyer tricking you into painting a fence; it’s your uncle “taking your nose”.

Rickroll’s mass appeal was in many ways a vanguard for internet cultural practices to come. Astley’s video was once only available when music television decided to broadcast it but it is now persistent, unfettered, and infinitely adaptable.

It’s not surprising that the original Rickroll video has been at the centre of so many takedown scares, nor will it be surprising if Sony decides to pull the plug for good. If and when that day comes, Sony would just be doing what so many in the internet meme-scape have been doing for years –- working to lock down their revenue streams. Tim Hwang, co-founder of the internet subculture ROFLcon conference, indirectly highlighted this point in a recent Forbes article. On why he and ROFLcon co-founder Christina Xu decided to suspend the ROFLcon series indefinitely, Hwang remarked, “by 2012 I was on the phone with GrumpyCat’s agent. It just didn’t seem fun anymore”.

The future of the original Rickroll video, like the future of so many internet memes, may ultimately come down to a business decision. But even if it’s taken down tomorrow, even if no one fills the void with a second (or third, or fourth) unauthorised video, Rickrolling, and all the cultural DNA it contains, will resonate from its historical throne, exemplary of broader folk practices. Like cotter548’s YouTube description says, “as long as trolls are still trolling, the Rick will never stop rolling”.