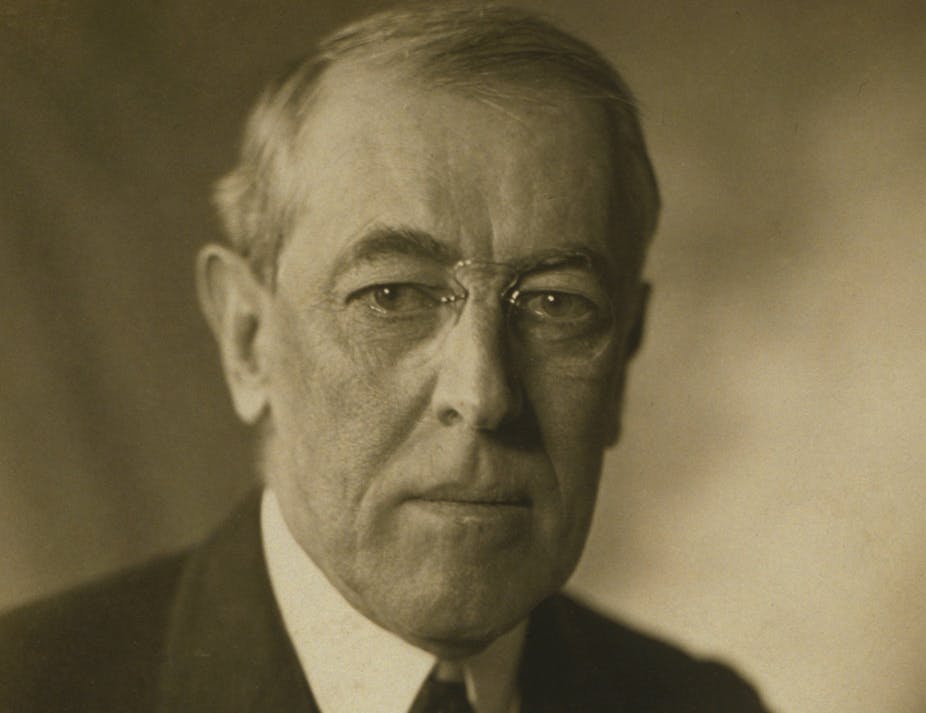

We have reached the centenary of US President Woodrow Wilson’s speech to Congress on January 8, 1918, outlining his Fourteen Points for brokering a lasting peace in Europe after World War I. It was the famous roar of idealism from across the Atlantic that would be whittled back in the name of self-interest by the victorious allies at Versailles the following year.

The speech would go on to shape many features of American foreign policy, however, particularly the broader points like open diplomacy, removal of economic and trade barriers, freedom of the seas and a general association of nations working together. Wilson would suffer a stroke that would partially paralyse him in the fallout from Versailles, but his Congress speech would ensure his legacy as one of America’s most influential presidents.

The centenary takes place just days before the anniversary of the inauguration of Donald Trump. With the media currently full of the astonishing claims about the administration contained in Michael Wolff’s new book, one wonders what the 45th president’s legacy will be. Certainly foreign policy looks more uncertain than for many years. What, then, do the Fourteen Points tell us about Donald Trump?

America front and centre

Wilson’s speech that day in 1918 reflected his conviction that the United States should take a central place on the world stage – securing global peace and stability while furthering American interests at the same time. His approach would be largely rejected by his countrymen during the isolationist 1920s and 1930s, before ultimately coming to define many Americans’ view of their country’s role in the world.

Since Trump came to power last January, it looks as if America has entered a new era. Many conservatives and rural middle Americans – the bedrock of President Trump’s support – have long been suspicious of America’s global role and complained about the ways in which the country’s foreign policy has been viewed by the rest of the world.

They feel that when America intervenes – as in the first Gulf War or in Afghanistan – it is accused of putting self-interest before the good of the international community. But when it doesn’t intervene – as in Bosnia or Syria – the accusations are little different. Why, they argue, should the United States be the world’s policeman?

This is clearly reflected in Trump’s National Security Strategy. Released in mid-December, it rejects many of the principles of previous American foreign policy, stating quite clearly that it must be “guided by outcomes, not ideology”. It is pure realpolitik.

The document promises explicitly to “put the safety, interests and well-being of our citizens first”. This includes building the infamous wall along America’s border with Mexico, withdrawing from many trade agreements which it sees as unfair, and beginning a substantial conventional and nuclear arms build up. It is America first from top to bottom – almost point by point a rejection of the ideas contained in Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

The great game

If this Trump strategy rejects the 20th-century concept of internationalism, it has surprising echoes of much earlier mid-19th century diplomacy. It says:

After being dismissed as a phenomenon of an earlier century, great power competition has returned.

Trump developed this point while outlining his policy to journalists, explaining: “America is in the game, and America is going to win.” The idea that foreign policy is a great game that can be won has echoes of Victorian men’s clubs, and is one of the most worrying changes initiated by Trump’s administration. It suggests a binary explanation of the world where there are only winners and losers, where those not participating in the game can be ignored.

But perhaps the most concerning shift of all, which probably echoes Trump’s personality more than his policy advisers, is the determination to conduct foreign policy “without apology”. Not only will the US put its own interests first, in other words, it will not deeply consider the interests of its allies.

Two recent policy changes reflect this. Following America’s withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement, the security strategy makes no mention of climate change as one of the issues facing the world, although it repeatedly discusses “the business climate”.

An even clearer rejection of internationalism was the December 6 decision to move the American Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. This was apparently against the specific advice of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, both of whom feared the impact on American diplomatic influence in the Middle East.

Big button diplomacy

This brings us to Twitter. Rather like 19th-century diplomats, where telegrams could spark wars, Trump seems often to have resorted to “Twitter diplomacy” to shape, or more often seemingly frustrate, American foreign policy.

President Teddy Roosevelt famously counselled that American foreign policy should “speak softly, and carry a big stick”. Perhaps nothing sums up Trump’s contrast to his predecessors than his tweeting – most recently the New Year’s Day reminder to North Korea’s Kim Jong-Un, in language more reminiscent of a primary school playground than international diplomats, that “I too have a nuclear button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his”.

None of this is to lionise Wilson, it should be said. America’s 28th president was no progressive on race, for example, and he invaded Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

But his Fourteen Points speech remains one of the great pieces of statesmanship of the modern era. Where it fought hard for stability, President Trump’s foreign policy seems more likely to produce instability. Where it fought for openness, the Trump administration turns inwards. It is a moment to reflect on what American leadership offered the world 100 years ago, and what it might learn to offer again.