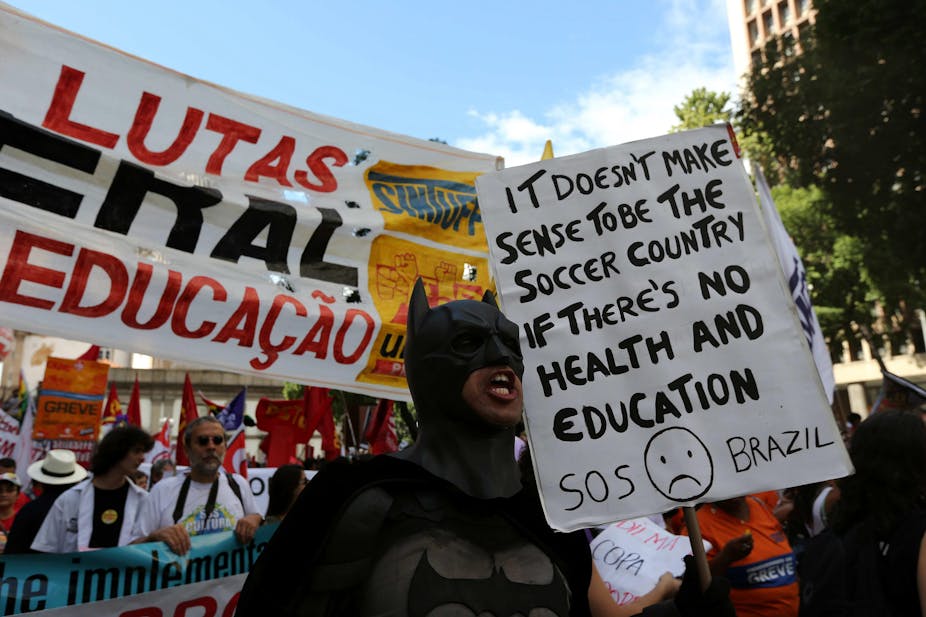

The 2014 World Cup and the Confederations Cup before it have acted as a catalyst for discontent being expressed by a broad sector of Brazilian society that feels indignant about the money spent on these sporting events rather than on improving education and health. As the tournament has progressed, there has been a quietening of activity on the streets, but it would be short-sighted to dismiss the significance of the protests that marred the start of the World Cup. Indeed, the nature of the demonstrations and those involved marks a significant shift in Brazilian politics.

Until recently it was the Brazilian Workers’ Party, together with the central unions and social movement organisations, who were at the forefront of protest in Brazil. But, now that they are in government, the anti-World Cup demonstrations caught them on the back foot. This public break between those in power and some of their traditional supporters is unlikely to be significant in the coming presidential elections, but likely to have an impact on political life in Brazil in the coming years. It undermines the Workers Party’s dominance of the Brazilian left, based as it has been on an opposition to privatisation and reductions in public spending.

Civil society in Brazil has been highly mobilised since the transition to democracy in 1985, thanks in great part to the contribution of the Workers’ Party. The demonstrations that we saw in the build up to the World Cup therefore shouldn’t be seen as a new phenomenon. It is also not new for the Brazilian urban, middle-class sectors to participate in mass public demonstrations: in 1992, for example, many mobilised to demand the impeachment of President Collor de Mello.

Previously, students were the main driving force of these carefully choreographed and successful demonstrations. But, unlike the demonstration against Collor, the current wave of social protest contains a more eclectic ideological diversity that gives it a distinct character.

Rising discontent

With the hosting of global sporting events, national identities tend to undergo a moment of reflexivity as a result of international exposure. This feeling overlaps with political necessity, which can then be exploited by Brazilian trade unions and political opposition parties – as is currently happening. The police of Bahia state, for example, staged one of the biggest police strikes ever recorded in Brazil. More than 130 people were killed in various crimes while the police withdrew from their duties. The teachers’ union also seized the opportunity to strike for better pay, and during a demonstration managed to stop the coach transporting the Brazilian national football team, winning publicity for their cause and in turn favourable conditions to negotiate.

The scale, composition and ultimately the political consequences of the June protests set them apart. On June 6 approximately 2,000 people gathered in São Paulo to protest against an increase in the bus fare. The meeting had been called by the Free Pass Movement, a social organisation whose main objective is to generate awareness about the importance of making public transport a public good, like health and education. What followed was a spectacular uprising nobody expected. By June 17, thousands of Brazilians were demonstrating in every major city of the country, including Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre and Belo Horizonte – all World Cup host cities. On June 20 protests spread like wildfire to all major and middle-size cities. Since then, protests continued but became more localised, less spontaneous and more organised.

By the time the government rolled-back the rise in bus fares it was too late. Protesters demanded more public investment to improve the health system, wider public transport and the education system. They were also protesting against police brutality in dealing with demonstrators, corruption at the hands of government officials, and FIFA’s ability to take over the public policy agenda.

Political implications

It is difficult to predict how this mobilisation will translate into electoral representation since it includes protesters and organisations from the far-left as well as from the far-right. What was initially a homogeneous issue-based demonstration, turned into a nationwide wave of social mobilisation, a heterogeneous movement in which activists and non-activists have found a common ground to voice their discontent.

According to opinion polls, the demonstrations seem to be having a limited immediate effect on the outcome of October’s presidential elections in which Dilma Rousseff is likely to be re-elected president. The protest will, however, have much wider political implications because they show the Workers’ Party cannot rely on support from the social movements from which it once was integral to and from which it gathered most of its transformative grassroots strength.

Over the past two decades, the Workers’ Party has forged its space in Brazilian politics in what could generally be called the “struggles against neoliberalism”. It had solidarity with other political organisations and social movements such as the Landless Workers Movement and in doing so defined what the left meant in Brazil.

But this narrative has entered a moment of crisis as a result of the anti-World Cup social protests. New demands and new groups have interrupted the public sphere, calling for their voiced to be heard. They no longer identify with the Workers’ Party, either because they have never believed their politics or because they feel betrayed by their actions in the build-up to the World Cup. And they are prepared to say this on the streets, in large numbers.

The overwhelming support of Brazil’s poorest is not going to be enough for the Workers’ Party to prevent the closure of its existing narrative, which has been fundamental to their 11-year reign. It is the first observable and significant political effect of the rebellion at the World Cup. A new consensus is in the making but its ideological content is yet unclear, precisely because it is currently being disputed.