In his poignant, much-acclaimed short story “Toba Tek Singh,” Pakistani playwright Saadat Hasan Manto describes the plight of Bishan Singh, an inmate of the asylum in Lahore. In the story, set in a post-Partition era, the governments of India and Pakistan decide to exchange inmates: the Muslims among them are to stay in Pakistan, while Hindus and Sikhs are to go to India.

Singh, whose native town Toba Tek Singh now lies in Pakistan, is asked to go to India, as he is a Sikh. Unable to comprehend the new realities of home and belonging, Singh struggles with a crisis of identity. In the end, the “madman” dies at the no man’s land on the newly carved India-Pakistan border.

The ‘insanity’ of dividing the mentally ill

The no man’s land in “Toba Tek Singh” could be symbolic of the space that the mentally ill spend their lives in – between institutions that feel burdened by them and a community where they are seldom welcome.

But the division of the mentally ill was hardly symbolic. The farce described in Manto’s story, where governments exchange inmates, did actually take place. After the division, the largest asylum in northern India fell in Pakistan. There were no asylums under the government in Delhi. Patients and their bodies became assets to be divided between the two nations. Lists were drawn up, and hundreds of patients were exchanged – a history that my fellow researcher Alok Sarin and I have recorded in our work on Partition.

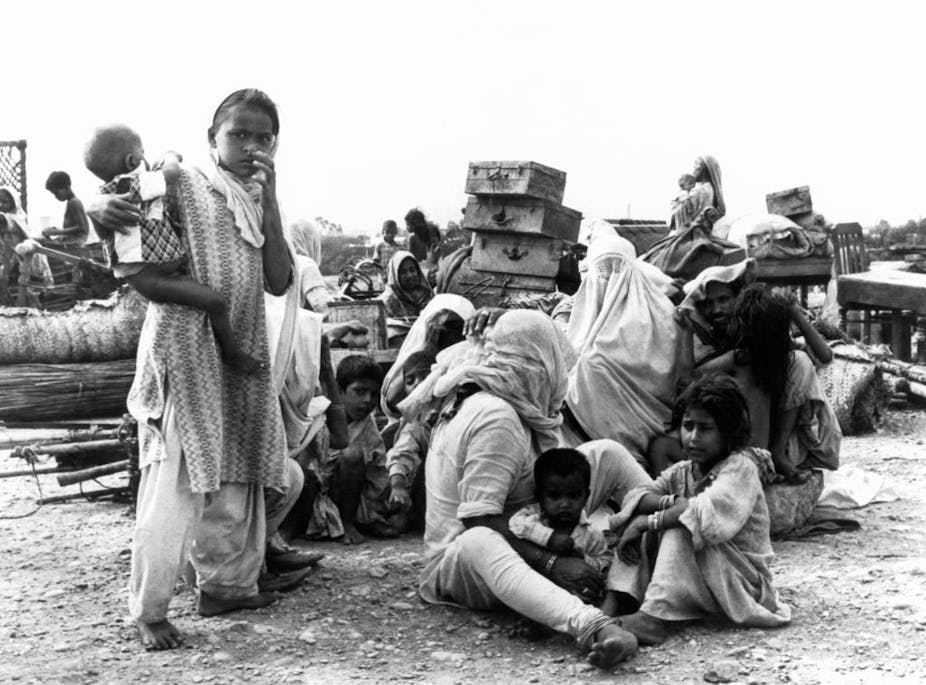

Non-Muslim patients were sent to India. The state of Punjab was divided between the two countries, and those who arrived from the area of the state that lay in Pakistan were housed in buildings and tents in the city of Amritsar in Indian Punjab. Others were sent as far away as central India, as no provincial government wanted to take responsibility of the new “others.” Several Muslim patients were sent to Pakistan from hospitals in India.

It is unclear how these persons were identified. Perhaps it was a bureaucratic response to make sure the burden was equally distributed. Thus attempts were made to arrive at somewhat equal numbers of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh patients to be shared across the new nations. Clearly, the new governments had not imagined the possibility that care might be delivered in a nonsectarian manner.

The unacknowledged trauma of Partition

The year leading up to Aug. 15, 1947, the day India gained independence, was perhaps one of the most violent in world history. Millions were forcibly moved, and at least a million killed or injured, because of the unimaginable atrocities that were perpetrated and experienced.

Before the Partition, in the late 1920s, a doctor conducting post-mortems on those killed in a communal riot noted that most injuries were on the victims’ backs, suggesting that the perpetrators’ sense of guilt made them avoid the victims’ eyes. By 1946, this sense of guilt had disappeared.

Doctors were shot dead at their clinics or on the road, a prominent hospital in Lahore was attacked, patients were killed inside hospital wards because of their identity, and more. This destroyed the idea of the hospital as a safe, secure, nonsectarian space.

Politicians on both sides of the border described the violence as “madness.” Eminent jurist N.H. Vakeel described the attempts at carving up the country and its people as the “political insanity of India.”

Doctors of the time felt that though the physical wounds could be treated, the “abyss in the soul” of the perpetrators would take decades to heal, if at all.

As early as the 1940s, historians such as Beni Prasad in India had warned that an undue emphasis on national identity tied up with religion boded ill for the future. This is similar to the critique of the Holocaust. Psychologist Erich Fromm, political philosopher Hannah Arendt and psychiatrist and political philosopher Karl Jaspers advocated universal humanism as a counter to the dangers posed by a national identity tied up in religion or myths of superiority. Universal humanism emphasizes the value of shared human experience.

Post-Partition, D Satyanand, the first professor of psychiatry at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi, wrote about the impact of the “low state of political, social and economic integration” on the mental health of its citizens.

However, he was optimistic that things could change if the “feeling of belongingness (that) is most essential” for positive mental health were nurtured. However, recurrent efforts to carve the nation along linguistic and political lines – more so after its independence – show the warnings have gone unheeded. A sense of belongingness and selfhood has suffered as sectarian and communitarian identities became commonplace.

The silences of psychiatry in South Asia

In India, formal attempts to study psychiatry began in the late 19th century, not too long after they did in the rest of the world. Most psychiatrists working in India, though British born or trained, were quite sure that there was no difference in the nature of insanity between the two societies.

Psychiatry in India fell short of assessing the events of the Partition. The experiences of hundreds of thousands who died or were displaced were met with a stony silence. There were only a handful of psychiatrists, and even fewer psychologists, in South Asia.

When we shared first-person accounts of the trauma experienced during Partition with mental health experts as part of a research project, almost all of them recognized the emotional and behavioral symptoms that would benefit from therapy, and perhaps even medication.

However, none of these remedies were available at the time, and issues were swept under the carpet. Psychiatrists know from other situations that a transgenerational transmission of trauma has significant effects on the psychological and even the biological health of subsequent generations.

By the mid-20th century, medical services – and thus, psychiatry – were thought of as an essential and fundamental need in the subcontinent. Before India became independent in 1947, the colonial Indian Medical Service supervised health care from the Suez to Singapore. Post-independence, though, this was the only imperial service that was specifically disbanded even as the police and administrative and defense structures were broadly left in place. By the mid-1940s, a national health plan had been envisioned for India, but its execution was watered down in the name of provincial autonomy – reflecting the attitude of early colonial rule, which centralized revenue but distributed responsibility.

The transfer of power did not really change matters, as the burden of caring for the mentally ill and addressing the trauma of the Partition proved too onerous for the newly independent nations. The consequences of this denial of care and the silences over the survivors’ trauma are being felt even today.