It’s been two years since the government announced it would establish a Home Affairs portfolio, and just over 18 months since it came into being. Since then, the department, and its high-profile minister and secretary, have attracted much controversy, discussion and criticism.

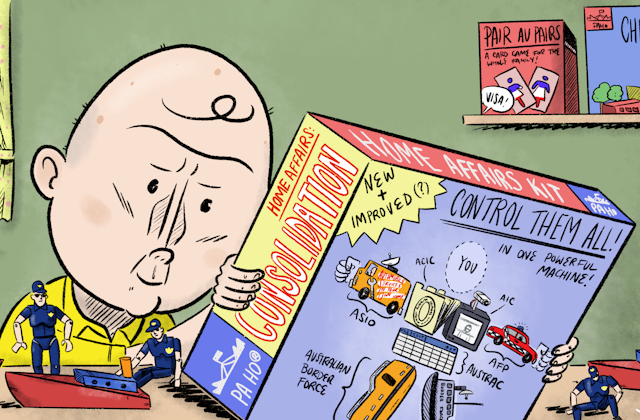

The latest debate centres on concerns that Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton is further consolidating power with legislation that would prevent foreign fighters from returning home for up to two years and the recent decision to move refugee services into his department.

There’s also been criticism that the portfolio is cloaked in secrecy, with some questioning why an internal strategic review of the ministry has not been made public.

Are we seeing an unprecedented consolidation of unregulated power? Or is there a reasonable story of good public policy behind the headlines?

Creating a single defence portfolio

These questions need to be placed in the context of both history and broader developments in home affairs policy.

We’re used to having a single Department of Defence in Australia. But it was only 40 years ago that the momentous decision was made to consolidate five departments — including one for each of the armed services — into a single agency.

There was push-back at the time from some agencies, and also a focus on the high-profile personalities involved in the process, including Defence Secretary Sir Arthur Tange, and his relationship with ministers and service chiefs.

Read more: There’s no clear need for Peter Dutton’s new bill excluding citizens from Australia

Decades later, the Department of Defence remains a large but effective organisation with a joint strategic and operational command, supported by a capable department. But its strategically important role and the significant resources needed to do its job mean it continues to require close management, attention and review.

Last year’s decision to take the Australian Signals Directorate out of the department shows it remains a work in progress, but one that continues to head in the right direction.

The lesson is that significant change in important areas of government policy, operations and services takes time, accompanied by ongoing review and revision.

Competing agencies and priorities

Before the Home Affairs portfolio was created, there were numerous security issues that cut across government agencies and demonstrated the need for a more strategic approach and greater collaboration among agencies.

The crisis around the unauthorised boat arrivals in the late-2000s, for example, created significant tension between the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) and the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO).

The high number of arrivals saw demands to speed up immigration visa processing. But ASIO was seen as delaying the process as it had to ensure the largely undocumented arrivals presented no security threat.

It was challenging for the two agencies, with such different responsibilities, to work through these issues. There was also pressure on the Australian Defence Force to provide the operational response at sea, and on law enforcement and customs officials investigating people-smuggling operations and other related crimes.

The agencies worked reasonably well together, but were often constrained due to their separate roles and protocols that did not support collaboration. They got through the crisis, with a lot of effort.

Read more: Politics podcast: Peter Dutton on balancing interests in home affairs

Counter-terrorism has been another major cross-agency issue. ASIO handled terror threat advisories and terror investigations (along with the police), while the attorney-general’s department oversaw countering violent extremism (CVE) policy.

The prime minister’s department was home to senior counter-terrorism and cyber-security coordinators, and the departments of defence and foreign affairs and trade ran their own counter-terrorism initiatives.

There was no single agency responsible for providing strategic policy direction on the issue until the establishment of Home Affairs.

One strategic policy home

The advent of Home Affairs means that complex and sometimes competing priorities have a strategic policy home and can be worked through at a portfolio level.

Immigration and ASIO are now in the same portfolio. Other agencies have also been added to the mix, including the Australian Border Force (ABF), the Australian Federal Police (AFP), the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC) and the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC).

Even in the short period since its creation, Home Affairs has made progress in providing more effective operations and services, supported by enhanced information sharing and technical capabilities.

For example, the department now has dedicated leads overseeing cross-agency efforts on counter-terrorism, cyber-security, organised crime and foreign interference.

Read more: The new Department of Home Affairs is unnecessary and seems to be more about politics than reform

Yet, the breadth of issues handled by the portfolio has also raised concerns about consolidation of power.

But most of the Home Affairs agencies are separate statutory authorities, retaining the independence and power established in their roles. The heads of ASIO and AFP, for instance, provide advice directly to the prime minister and cabinet when required and carry out their own operations.

In the aftermath of the AFP raids on media organisations, both Dutton and AFP Commissioner Andrew Colvin confirmed the minister had no involvement in the operations.

Ongoing communication and appropriate oversight

The most important issue facing Home Affairs is the need for clear communication to the public on what the department does, why it’s important, and how its work is carried out. That must also include assurances the department has appropriate oversight and accountability systems in place.

This is easier said than done in the highly charged political atmosphere that’s surrounded Home Affairs since its inception.

It’s good news, then, that Labor chose to establish a shadow home affairs minister after the federal election, thereby working with the new Home Affairs arrangements and letting the portfolio as a whole settle down.

The oversight and accountability mechanisms are also doing what they’re supposed to do. The proposed security laws, for example, were scrutinised by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS), which recommended changes to reduce the minister’s power.

Most suggestions were incorporated in the revised legislation, though Labor still has concerns about the minister’s power to grant a temporary exclusion order (TEO) for returning foreign fighters. The PJCIS will continue to examine the use of TEOs, as will the Independent National Security Legislation Monitor and other oversight organisations.

The PJCIS is also due to report to parliament in October on its inquiry into press freedom, which will shed light on issues related to the AFP raids. And we’ll likely see the key findings of Home Affairs’ internal review as its annual report and regular Senate Estimates appearances approach.

Why it should work

The creation of Home Affairs enables a more strategic and integrated approach to security, law enforcement, migration and border issues. It also means more efficient delivery of services.

But there are significant challenges to doing this and getting it right, particularly while managing such a vast portfolio of operations and responsibilities. Maintaining a balanced approach, and ensuring considered and appropriate oversight and review will be critical to its success.

More than 40 years after its creation, the Department of Defence is held up now for its strategic vision and stewardship of the country’s armed forces. The divisive politics surrounding its creation have long been forgotten.

And so it should be with Home Affairs. The creation of the portfolio is ultimately a good thing for Australia and for good public policy and services. But this is a long-term endeavour and the project is still in its early days.