As Britain starts four years of commemorating the centenary of the First World War, Blackadder Goes Forth, first broadcast on BBC1 in 1989, has, bizarrely, taken centre stage.

To rather less fanfare than Michael Gove’s claim that Blackadder made Britons think the war was a “misbegotten shambles”, last autumn Defence minister Andrew Murrison and Jeremy Paxman said very much the same thing. And before Gove turned the issue into a party spat, Dan Jarvis, Labour’s shadow Justice minister, argued Blackadder promoted an erroneous “pointless futility” narrative about the war.

Blackadder is not alone in constituting that which Gove described as the “fictional prism” through which we now see the war. The 1963 musical Oh! What a Lovely War, the 1986 BBC drama series The Monocled Mutineer and the war poets have all been mentioned in dispatches. But it is the comedy series written by Ben Elton and Richard Curtis upon which the fire has been fixed.

There is a long history of authority figures blaming films, television shows, plays or even pop songs for causing people to think or do things they don’t like. But why is there such concern about how Blackadder has affected perspectives of a war at whose outbreak fewer than 11,000 of today’s population was alive?

Gove appears to be on a personal mission to persuade the British to adopt a view of the conflict which emphasises the “patriotism, honour and courage” of those men who fought in what he describes as a “just” war. But there is more at stake than that, and it is something that unites all members of our political class.

Murrison told fellow MPs that he wants the centenary commemorations to rehabilitate those political leaders that the Blackadder version presents as “willing consigners of other men’s sons to hideous death”. Even Nigel Farage – for the moment at least, no friend of Britain’s current political elite – has defended the generals from their sitcom depiction as incompetent fools.

While Jarvis conceded Blackadder “serves as a powerful testimony to the savagery of World War One” he still argued that it distorted historical reality. Even more tellingly, at the same time Tristram Hunt attacked Gove for playing party politics with the conflict, he highlighted those “patriotic” Labour MPs who were recruiting sergeants for the trenches. If he suggested that more countries than Germany were to blame for the war, Hunt did not question its status as “just”.

It is perhaps no coincidence that authority figures of the present want to rescue the authorities of the past from the comedic contempt of posterity. Nor is it surprising that critics of the Westminster consensus, like Seamus Milne, claim the Blackadder version reflects the truth of what they see as an imperial conflict that sacrificed millions in the deadly pursuit of profit.

But what does everybody else think about the war? Think-tank British Future tried to find out last year. They discovered that that while 19% of Britons believe the World War I was “futile”, 33% consider it to have been “just” – between one-third and a half simply did not know what to think.

On that basis Gove et al might stand easy. But a more detailed breakdown of the figures suggests otherwise. The survey revealed that only 16% of 18-24 year olds think the war “just”, while 24% believe it “futile”: it is the only age cohort in which more favour the Blackadder version over the one promoted by Gove and the rest.

The young’s greater scepticism about the “just” character of World War I probably has less to do with Blackadder - first broadcast before most of them were born - than their more general mistrust of contemporary political authority.

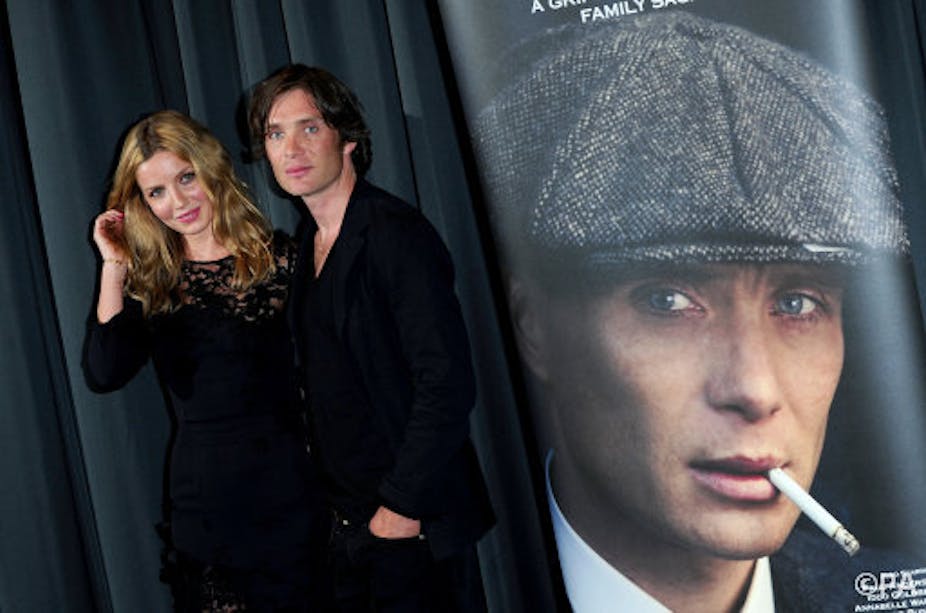

But if Westminster wants to worry about the influence of a television show, MPs might be better advised to stop obsessing about a two decades old sitcom and turn to BBC2’s 2013 drama Peaky Blinders.

Clearly aimed at a young demographic, it depicts a generation of men who are brutalised by trench warfare and alienated from all forms of authority as a result. Just demobilised, the gang swells to include a corrupt police force and politicians, notably a Winston Churchill who is willing to turn a blind eye to murder.

Depicting a futile war followed by an unjust peace, if Peaky Blinders has any resonance with its audience – and it will be coming back for a second season – Gove, Hunt and even Farage should be very worried indeed.