I will often say to my film students that if you want to know what aches a culture at a particular historical juncture then you need to visit and spend time with the catastrophic imagination of science fiction. For it is in the restless dreaming of future horizons where the hopes and fears of the present are laid bare.

Showing at the Melbourne International Film Festival in a lush restored 35mm print and with its original montage ending restored, Phase IV - the only film to be directed by the exquisite poster and title sequence designer, Saul Bass - explores what happens when humankind is threatened by hyper-intelligent ants intent on colonising Earth.

Set in the Arizona desert – but filmed at Pinewood Studios in England and on-location in Kenya – Phase IV narrates the struggle between two scientists, James Lesko (Michael Murphy) and Ernest Hubbs (Nigel Davenport) as they seek to understand and overcome the mysterious unification of all ant colonies and the (alien) hive mind that controls and advances their collective cause.

It is suggested that if Lesko and Hubbs cannot stop these super ants, then human civilisation is doomed. Doomed, I tell you.

Doomsday visions

Visually and aurally the film is indebted to a heady mixture of influences including the wildlife documentary; the anti-realism of European art cinema; the topography of the desert Western and the rural road movie; and to the new wave of electronic music and atonal chords that is so effectively used to eerily score the film and its often ferocious feral sound effects.

The ants enunciate like a ravenous and telepathic army on the relentless march to herald in the Armageddon, while the bleeps, squeaks, hums and drones that also saturate the soundscape creates the impression that invisible forces haunt every space.

These are not ants that can be trampled upon or squished between ones fingers but super centurions of the insect world.

The film’s cinematography is composed of two distinct styles.

Firstly, there are the intimate and naturalistic close ups of the ants, their colonies, machinery, computers, the sun and the moon, obelisques, and the various textures - such as skin, electrical wires, yellow poison - that colour and wash the entire mise-en-scène.

One feels as if one is in the laboratory or desert with the ants, and in that transferable relationship between film and viewer, as one watches one scratches skin and hair as if their phantom legs are beginning to crawl over and burrow down deep into you. This is carnal science fiction cinema.

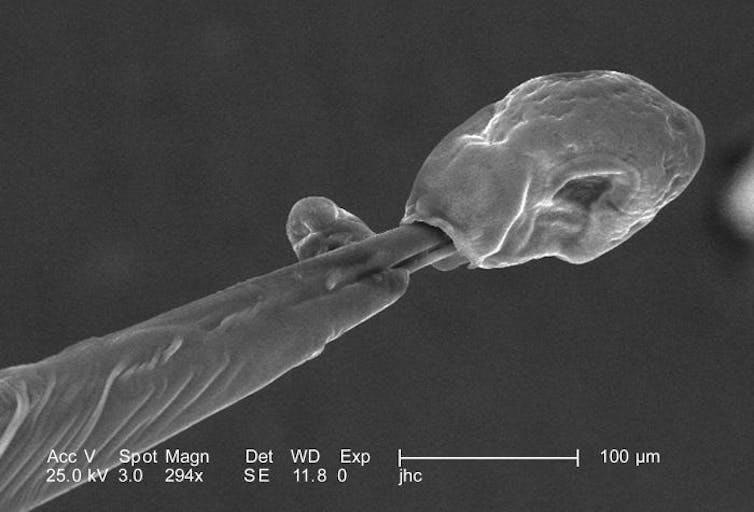

The wildlife photographer Ken Middleham shot the insect sequences for Phase IV, as he also did for the documentary The Hellstrom Chronicle. Through a microscopic lens, the anatomy of an ant has never been so diabolically well chronicled.

Phase IV is also composed of long shots, frames of deep focus and wide panoramas, so that the shimmering heat of the desert and the liquid fire of the sun appear enormous and awesome in their power. The film is full of sublime cinematography. It simply takes one’s breath away and makes one feel like a tiny dot, like a single ant, in a giant universe.

This oscillation between near and far, between claustrophobia and agoraphobia, positions Earth in a never ending and expanding cosmos, but also under a forensic microscope where all our activities are being closely monitored. Ultimately this is a film caught in a paranoid state of delusion and allusion, as the troubles of America seep its way into its metaphoric visual and aural palettes.

Signs of the times

Narratively, Phase IV speaks to a number of critical concerns of America at the time the film was made: ecological and environmental collapse; the Cold War, and the Vietnam war; the ambivalent relationship that society has to science and their hyper-rationalist scientists; and to the irrational fear of miscegenation.

Phase I: Ecological and Environmental Apocalypse

One of the concerns of Phase IV is the relentless expansion of the suburbs, population growth, unsustainability and the mechanisation of farming.

The film’s first land-based shots are of new town billboards and half completed homes. The yellow poison used to destroy the ant colony is a coda for industrial fertilisation and the dangers it brings to agriculture. The ants, which wipe out species that are above them in the food chain, are the avatars that put the ecology of Earth out of balance and as a consequence threaten the survival of all species, of the planet itself.

However, we realise late in the film that they are actually custodians of the future – it is we who must be stopped or over-taken in the evolutionary chain if Earth is to prosper.

Phase II: Red Ants under the Bed

Phase IV was made at a time when the Cold War and Vietnam was uppermost in the American nation’s psyche. The ants in the film become both the fifth column, and the personification of Soviet norms – working collectively for the greater good and without individuality or individualism, always willing to sacrifice so long as the cohering centre is maintained.

The ant army can also be likened to the Viet Cong or the National Liberation Front, fighting against the superior technology and firepower of the American military. The ants build a series of connecting tunnels and traps, infiltrate the compound, and in consort with the “natural” environment turn the desert and sun on the scientists.

The scientists, secured in their hi-tech fortress compound, use yellow poison (agent orange, napalm) to kill the ants, but the ants only grow stronger. Eventually, the scientists have to abandon their laboratory and the ants begin to secure their victory as their centurions march on its grounds.

Phase III: Mad Science

Phase IV offers up an ambivalent representation of science. Hubbs is the archetypal mad scientist, one who seeks truth in rational method and through reason alone, but is solely intent on destroying the ants at whatever cost. He uses science in a destructive way and is impervious to the human death that occurs around him. The film is a warning about letting too much science into the world.

By contrast, Lesko is the humanist scientist. Through his mathematical formulations he seeks to communicate with the ants, to understand them better. Lesko cares about human and ant life and looks to reason and emotion to bridge the species gap.

However, the film suggests that Hubb’s approach maybe the one that needs to be followed, offering the viewer a powerful Cold War message about weapons proliferation and the need for aggressive responses.

Phase IV: Inter-Species coupling

Phase IV has a fear of borders being breached and is full of images of thresholds being overtaken, overrun. The film offers us images of “white flight” in which the ants become marauding rioters intent on taking over the “neighbourhood”. There is one scene of a house being “looted”, flames licking its grounds. The film’s context can be set in the context of the race riots and civil rights abuses that dominated the period.

Nonetheless, Phase IV brings the two species together, ant and human, suggesting that in their communion a new dawn will be reached, a new age will be born. In the newly restored cut of the film, this future horizon is a psychedelic trip where a new inter-species reaches the astral plane.

The Melbourne International Film Festival 2014 screened during August 2014. See all MIFF 2014 coverage on The Conversation here.