David Duke, the blow-dried wizard of Louisiana politics, is back. This time he is running to represent Louisiana in the U.S. Senate.

When asked by journalist Tyler Bridges if he appealed to the same voters as Donald Trump, Duke replied:

“He’s getting the same kinds of votes that I have gotten in Louisiana. He’s getting the same kinds of votes that [Pat] Buchanan got. He’s getting the same votes as George Wallace.”

As scholars of southern politics, political campaigns and public opinion, we thought Duke’s time had come and gone. His reemergence during the deeply divisive Donald Trump presidential campaign gives testament to William Faulkner’s observation in “Requiem for a Nun” that “the past isn’t dead, it isn’t even past.”

The seeds for Duke’s reemergence as a candidate – ironically enough, we contend – were sown by the election of the nation’s first African-American president. Rather than bridging racial divides, those divides have deepened over the course of Barack Obama’s administration. Issues not traditionally associated with race, such as health care, have become racialized. Old-fashioned and outspoken racism has replaced the softer, coded and unspoken symbolic racism that has defined the past several decades.

What Duke represented and still represents – the lingering stain of racial resentment – remains an unfortunate but resilient strand of American political thought. In the America of 2016, racists can put down their dog whistles and just yell for their dogs.

Or, they can run for the U.S. Senate.

From racist to representative

Duke spent his college days at Louisiana State University from 1968 to 1974, preaching white supremacy while recruiting for the Ku Klux Klan. He was dismissed by journalists as one of those asteroids following its own orbit in the lunatic fringe. Throughout the 1970s and ‘80’s he was active in white supremacist circles, creating his own civil rights group, the National Association for the Advancement of White People, and running as a perennial Democratic candidate for offices ranging from the state legislature to the presidency. Then in 1989, running as a Republican, he won a special election to the Louisiana House of Representatives, where he served from 1989 to 1992.

Success fueled Duke’s ambition and provided the springboard for two serious bids for statewide office. Foreshadowing the Trump campaign, the GOP establishment disavowed Duke. Nonetheless, he won 43 percent of the vote in his 1990 Senate race against incumbent U.S. Senator Bennett Johnston. Then, he won 39 percent in an encore performance in the gubernatorial election against the ethically challenged Edwin Edwards in 1991.

In both contests, Duke won the bulk of the white vote while running against experienced and well-known officeholders. Edwards won thanks to high turnout, especially among African-Americans motivated by the call to “vote for the crook, it’s important.” Perhaps ironically, both the crook Edwin Edwards and the Klansman David Duke would later spend time in a U.S. penitentiary: Edwards for bribery and extortion and Duke for “bilking his supporters and cheating on his taxes.”

In 1996, his novelty having worn off, Duke won only 11 percent of the vote in his second run for the Senate. In 1999, he took 19 percent in a special U.S. House of Representatives contest.

Duke and Trump: Overlapping voters?

Duke’s relative success spawned a small cottage industry of academic research as scholars grappled with what the electoral viability of a Klansman meant to democratic governance.

The research uncovered that long before Trump entered the nation’s consciousness as a reality show host, Duke honed a message that resonated with white working-class voters struggling economically, angry at an economic and political system that had grown callous to their needs, resentful of establishment career politicians, and ready to scapegoat emerging minorities. When asked in early August if Trump voters were also his voters, Duke observed:

“Well, of course they are! Because I represent the ideas of preserving this country and the heritage of this country, and I think Trump represents that as well.”

Duke’s claim has merit. Looking at votes cast for Trump in the 2016 GOP primary by county, what Louisiana calls “parishes,” shows that Louisianans voted similarly to how they voted for Duke in the gubernatorial primary in 1991. In 40 of Louisiana’s 64 parishes, Trump’s actual support in the 2016 presidential primary is within five percentage points of an estimate from a statistical model based only on Duke’s percentage of the vote in 1991. This is not just partisanship at work, as Louisiana uses a closed presidential primary system, which prevents strategic Democratic voting.

Why is this the case?

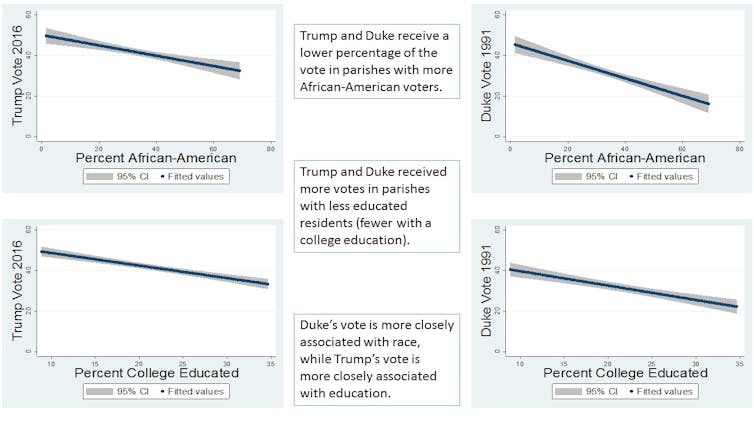

Both Duke and Trump received larger shares of the vote in parishes where the population is mostly white, rural and less educated. They both did relatively poorly in more urban parishes like New Orleans, East Baton Rouge and Caddo with large African-American populations and more college-educated residents.

Using statistical models based on these data, we found that relative to David Duke’s vote, Trump’s vote is more closely associated with education, meaning he pulls more strongly from less educated voters. Duke’s vote is more closely associated with race. But, if there are differences in their bases of support, the similarities are even more striking, especially given that a quarter of a century has passed since Duke’s 1991 campaign.

Given the similarities in their support, it is not surprising that Duke endorsed Trump. Trump, as has been his pattern, reacted in multiple ways – feigning ignorance of Duke and his past before shying away. Regardless, they share the same base of racially resentful voters.

As political scientist Phil Klinkner recently concluded, racial resentment, even more than economic anxiety, was driving voters to Donald Trump. David Duke was smart enough to read the tea leaves. If Trump was winning nationally, Duke’s message might once again find resonance locally in Louisiana.

While this explains Duke’s decision to run, we have our doubts about his ability to run competitively or win statewide in 2016. Duke’s days as the messenger of racial resentment are hopefully long gone. Twenty-five years have passed since we thought of him and his message as an echo. The Trump campaign serves as a reminder that Duke’s message still finds resonance with voters, and voice from ambitious, unscrupulous politicians. Donald Trump is only the latest and most visible example tapping into this undercurrent of American political thought.