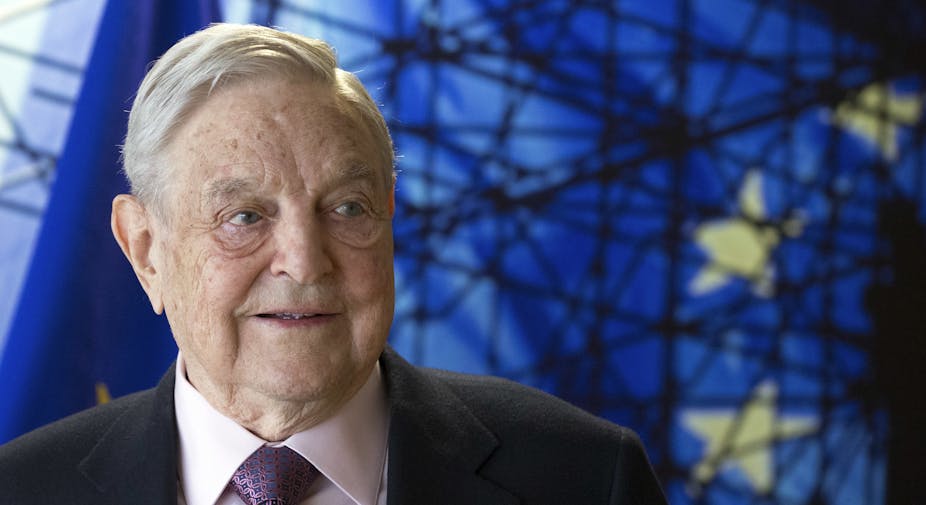

Billionaire investor and philanthropist George Soros is handing control of his US$25 billion holdings, including his Open Society Foundations, to one of his sons, Alexander Soros.

As a sociologist who researches immigrants and minorities in Europe and conspiracy theories about them, I study how Soros became a scapegoat and bogeyman for nationalists and populists and a target of people who harbor and spread antisemitic beliefs.

Baseless conspiracy theories have at times clouded his legacy as one of the world’s biggest donors to causes like higher education, human rights and the democratization of Europe’s formerly communist countries.

Success followed early hardship

Born in 1930 to a Hungarian Jewish family, Soros survived the Nazi occupation and the Holocaust. After World War II, he moved from Budapest to the United Kingdom, where he studied at the London School of Economics while working part time in low-wage jobs. He immigrated to the United States in 1956 and became a U.S. citizen five years later.

In the 1970s, Soros became a successful investor and hedge fund manager. By the 1990s he had amassed a fortune and established himself as one of the world’s most important financiers.

But his dedication to philanthropy and his support for political freedom are what brought him the most attention.

Deep-pocketed philanthropy

In the 1980s, Soros began to contribute to several Eastern European political and social movements that sought to replace communist states with democratic societies. Recognizing the importance of grassroots movements and the power of individuals to bring about change, his support enabled many activists to challenge oppression and advocate for human rights.

He also donated heavily to support education.

Soros’ first philanthropic foray was in 1979, when he funded scholarships for Black students in apartheid South Africa. In the 1980s, he helped promote the exchange of ideas in Communist Hungary by funding visits of Hungarian liberal intellectuals to Western universities.

When he gave $250 million in 2001 to the Central European University in Budapest, it represented, at that time, the continent’s largest higher education endowment.

Soros founded what’s now called the Open Society Foundations in 1993. The name of this international grant-making network was inspired by Karl Popper’s 1945 book “The Open Society and Its Enemies.” Popper argued that individuals thrive in open societies, because they can freely express themselves and test their ideas, while closed societies lead to stagnation.

The broad goal of much of Soros’ philanthropy is to support tolerant societies with governments that are accountable and allow everyone to campaign, protest, donate to candidates they like or even run for office themselves.

Soros’ foundations today support human rights organizations in more than 100 countries. Its initiatives take aim at a wide range of global problems, such as public health emergencies to low economic growth rates in low-income countries.

Soros remains on Bloomberg’s list of the 500 wealthiest people, with a personal net worth in excess of $7 billion as of 2023. But his fortune would have been far larger had he not given some $32 billion to the Open Society Foundations since 1984.

Antisemitic conspiracy myths

The Open Society Foundations’ support for progressive initiatives such as America Votes and Demand Justice have angered many conservatives who don’t agree with the goals of those causes.

Soros’ wealth and influence have also made him a target of numerous conspiracy theories. He’s been demonized as a shadowy puppet master manipulating world events for his own gain. Such baseless accusations often target his Jewish heritage, invoking hatemongering and centuries-old antisemitic tropes.

During the 2015 influx of Syrian refugees in Europe, for example, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán accused Soros of a vicious plan of facilitating a supposedly “Islamic takeover of Europe” with the Syrian immigrants.

Former Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico blamed Soros for being behind press freedom protests in his country after the murder of the investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée in 2018.

In 2015, the far-right party All-Polish Youth burned an effigy of Soros dressed as a Hasidic Jew holding an EU flag, even though the philanthropist was raised by a family that was not religious, has never dressed in the style of the ultra-Orthodox Hasidic sect and has not been a major supporter of Jewish causes.

As I explained in a book chapter about nationalism and populism, U.S. conspiracy theories have hounded Soros for years as well. Rep. Kevin McCarthy, a California politician who is now speaker of the House, accused Soros of trying to buy the 2018 midterm elections. National Rifle Association leader Wayne LaPierre accused Soros of planning a socialist takeover of the U.S. in 2018, evoking antisemitic myths from the early 20th century about a Jewish-Bolshevik plot.

That same year, then-President Donald Trump falsely tweeted that Soros was financing the demonstrations against Brett Kavanaugh’s appointment as a Supreme Court justice.

These baseless theories have also inspired extremists to act on them: In 2010, a far-right extremist plotted to attack the progressive San Francisco-based Tides Foundation. His plot failed and ended in a shootout with police officers, and the man was sentenced to 401 years in prison. The extremist falsely believed that Soros used Tides “for all kinds of nefarious activities.”

In 2018, another extremist sent a pipe bomb to Soros’ home in a New York City suburb. Nobody was hurt, but the person responsible was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Many other far-right extremists have tried to justify their attacks on Jews and other minorities with anti-Soros conspiracy theories – including the man who murdered 10 Black Americans at a supermarket in 2022.

A complex legacy

Not all criticism of Soros is antisemitic.

While I do believe that Soros’ support for freedom and his commitment to empowering marginalized communities are praiseworthy, I also think it’s reasonable to question the sources of his wealth and the methods he employed to accumulate it.

As is true for all billionaires, the Soros family fortune helps perpetuate a system of income inequality and concentrated political influence in the hands of the world’s wealthiest people. I believe that this outsize clout interferes with true democracy.

George Soros has certainly funded work through charitable donations that has fostered democratic values. But his financial support in the political realm, which includes gifts for major Democratic political causes and candidates, such as former U.S. President Barack Obama, former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and President Joe Biden, have to a degree made him a polarizing figure.

When megadonors of any political preference make big donations to a candidate or party, their gifts can shape the agenda and distort democratic processes.

In his first interview as the new chair of Open Society Foundations, 37-year-old Alex Soros told The Wall Street Journal that he is “more political” than his father and that he’s likely to make political donations that advance voting rights and abortion rights.

It’s still not clear how Soros’ son aims to put a stop to the demonization of the family’s philanthropic work.