Formal education in the Gold Coast, now Ghana, was introduced during the 15th century when Europeans came to its shores to trade. Education was only accessible to children of women married to western traders, and it focused on teaching them how to read and write. The primary aim was to create an educated class to support and run colonial activities.

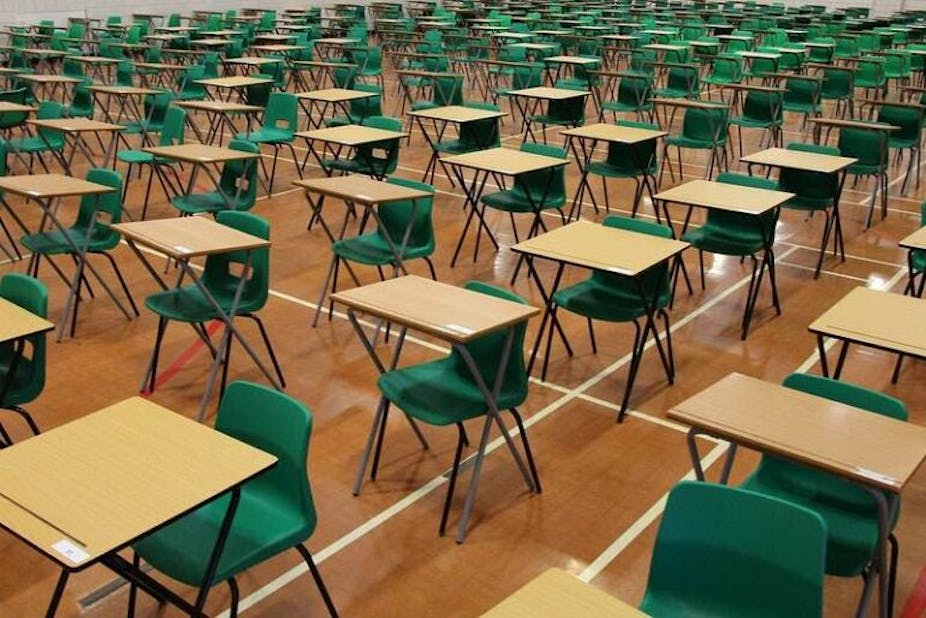

By 1882, Britain was established as the colonial power in the region. Educational opportunities were limited, and educational assessments served as the gatekeeper to education. They focused on academic knowledge and English proficiency. Results were used to select students for higher education and white-collar jobs.

The roots of this practice are still evident in Ghana’s education system. Students are streamed into three tiers of secondary schools, with disparities in educational resources across streams.

Our recent study explored the history of educational assessment in Ghana, and how colonisation and political accountability shaped the use of assessment information in schools. We observed that assessment has primarily served accountability purposes, obscuring its function of improving students’ learning.

Influence of colonisation

The colonial legacy of assessment still influences Ghana’s current testing practices, through a system that emphasises imperialist notions of merit and achievement.

The West African Examinations Council, responsible for mandated tests in anglophone west African countries, including Ghana, was established by the British in 1950. Ghana’s assessment system still relies largely on this framework, as western universities require excellent scores on these tests for undergraduate admissions. Additionally, high-stakes examinations persist due to the pressure to meet global education standards through international comparisons of student achievement.

Political accountability

It is common for Ghanaians to measure the quality of education by the number of students who pass the national mandated testing. Student assessments are used as political performance indicators and tools for public policy and political accountabiltiy. For example, over the past five years, the government has invested about US$5.8 million to buy past exam questions to assist students.

Teachers are also held accountable for students’ performance in national exams. As a result, they end up teaching with the primary motive of preparing students for these tests. Educators and students focus on exam success rather than learning.

Free schooling

To support inclusive and equitable access to education and increase enrolment rates, Ghana introduced a free senior high school policy in 2017. Yet disparities in access to and enrolment in secondary education persist between children from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

Critics argue that the policy was hastily implemented for political reasons, lacking proper consideration of its long-term implications and costs. Others argue that the policy is a way to increase enrolment in secondary schools.

Importantly, its effectiveness is tied to students’ performance in the Basic Education Certificate Examination. A student’s outcome on this examination also determines their placement in one of the secondary school streams via a computerised system.

Read more: Ghana's high school system sets many students up for failure: it needs a rethink

The policy mostly benefits students who pass the exam and qualify for placement. Those who come from low socioeconomic backgrounds or rural areas are often at a disadvantage.

Failing the exam hinders students from progressing to senior high schools or technical institutes in Ghana.

Influence of high-stakes exam

The high-stakes nature of large-scale assessments in Ghana’s education system fosters disengagement among poor students and teachers.

The focus on exams overshadows the intended learning goals of teaching and many other forms of assessment. Evaluation of teachers and schools is linked to student performance in tests. Teachers therefore tend to narrow their curriculum to what’s tested. This means:

creativity and meaningful learning are eroded

some pupils struggle to master the curriculum content

there’s less teaching time for students with special needs

there may be unethical practices to ensure students pass.

Students from low socio-economic backgrounds and those with special learning needs often find themselves marginalised by these assessments. Ultimately, the results of large-scale assessments segregate students into categories of secondary schools, based on limited resources.

Future directions and policy implications

The principle of fairness implies that students’ progression shouldn’t rely on a single test score, as is the case in Ghana. To meet the country’s equity goals, the system should consider diverse indicators and assessments of student learning.

The educational access policies of Ghana provide an opportunity to reform assessments. They can shed their colonial roots and encourage high quality teaching and student learning.

Reformed policies should balance various forms and purposes of assessment, and provide teacher guidelines and professional development.

Transforming Ghana’s testing culture to one that supports meaningful learning and equitable educational outcomes is a considerable challenge. But it’s an essential one if the country is to reach equitable education for all.