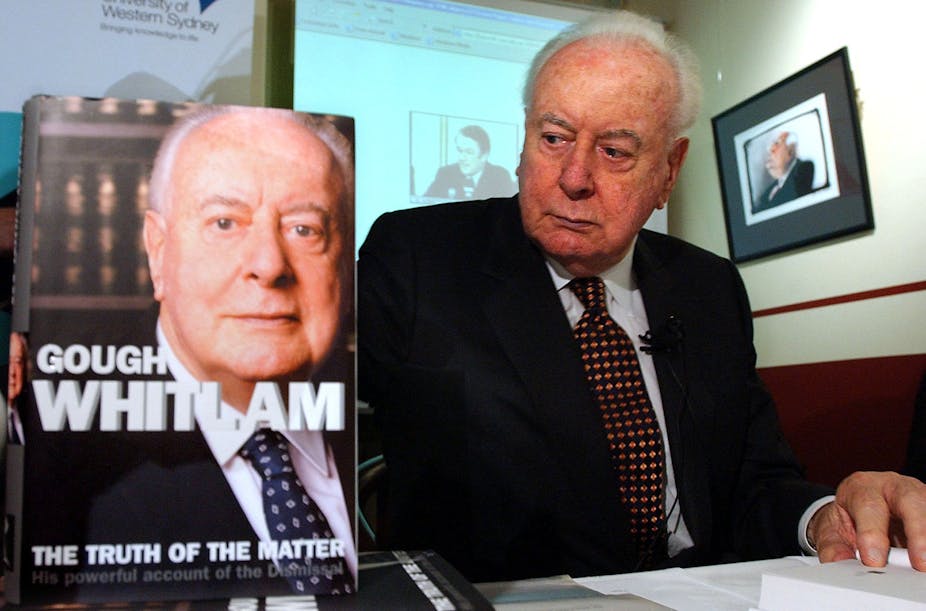

How can Labor regroup after the trauma of its defeat at the federal election? The best example the past offers is how the party rebuilt after the tumultuous prime ministership of Gough Whitlam in the mid-1970s.

At that time, Labor sought broad advice - not just from “party elders” - and adopted a radically new policy idea: the Accord. Since the 1970s, however, Labor’s response to defeats and disappointments has become increasingly inward looking.

After the 1975 election whitewash, the need to confront Labor’s defeat was delayed by rage at the Dismissal and by emotional loyalty to Whitlam. It was Labor’s disappointing performance at the 1977 election that forced the party to confront its future.

Labor supporters came to terms with the prospect that the Whitlam government had just been an interregnum in a conservative ascendancy. Conservative political scientist David Kemp argued that Labor’s values were fundamentally at odds with an increasingly conservative and suburban working class.

Labor’s response to 1977 was to commission the first of many modern reviews into its performance and prospects. Unlike later reviews, this was not undertaken by party “elders” alone. It included sympathetic academics such as sociologist Sol Encel, and a rank-and-file branch member.

It was only after a protest that women were included on the committee, but the report had a lasting legacy, with its conclusion that Labor reach out to more diverse constituencies, in particular female voters.

In the post-Whitlam years, Labor also drew on the advice of sympathetic economists who encouraged the party to support an “incomes policy” to enable non-inflationary economic growth. The Accord underlay the success of the Hawke government, even if it may have had dangerous long-term consequences for Labor support. The Accord did not emerge from within the narrow confines of the parliamentary Labor Party or the musings of “party elders”.

Labor was unsure about how to respond to its 1996 defeat. The defeats of 1975 and 1977 could be interpreted as the result of a desertion of middle ground swinging voters, but in 1996 there was a particular erosion of support for the party among core supporters: workers without university qualifications and non-Anglo ethnic communities. Labor was divided as to why this had occurred: some blamed “economic rationalism”; others Keating’s “big picture” agenda and his appeal to the intelligentsia.

Labor’s self-absorption after 1996 was limited by two factors. Firstly, the Howard government drifted for its first term and then tied its fortunes to the risky prospect of the GST. Also, Kim Beazley as Labor leader demonstrated an avuncular charm that endeared him to party members and voters rather like Anthony Albanese today. In early 2001, a Labor victory seemed certain.

The 2001 election result was more traumatic for Labor than the defeat of 1996. Labor insiders saw their hopes of a return to government dashed and party activists were deeply estranged by the party’s acquiescence in much of the Howard government’s policy against asylum seekers.

In the aftermath of defeat, new leader Simon Crean - a policy-focused party insider rather like Bill Shorten or Julia Gillard - placed great hope in a review of party structures undertaken by Hawke and former NSW premier Neville Wran.

The conclusions of the report, however, had little impact. Crean was diverted into a symbolic battle to reduce trade union representation and the report’s advocacy of direct representation for party members in decision-making led only to the creation of a powerless office of national president.

A separate policy review chaired by Jenny Macklin was overshadowed by Labor’s leadership struggles, and at the 2004 election it was Mark Latham who set the policy agenda.

The traumas of 2010, and in particular the rise of the Greens, led to another inward-looking review conducted by party elders: former state premiers Bob Carr and Steve Bracks, and senator John Faulkner.

This retrod some of the same ground as the Hawke-Wran review. It gave slightly more attention to policy and instanced the Hawke government as a model combination of economic reform, environmental awareness, and fidelity to concerns of traditional Labor voters.

It was Kevin Rudd on his return to the prime ministership in 2013 who was far bolder than the report in advocating the direct election of the party leader.

There will always be a centre-left party in Australia, and the current Tasmanian example suggests that the Greens will not do a better job of this role than Labor. Conservative overreach and self-absorption will eventually return Labor to national government.

Yet, for Labor, the question is not about survival. If the party is to be worth taking seriously by those concerned for Australia’s future, it must become a policy-focused force, which it has not been for decades. There is little more to be argued about party reform.

Labor would be well-advised to consider some fundamental questions. Was voter angst about living standards illogical? Is the paternalist trend in social policy - manifested in initiatives such as the Northern Territory intervention and income management - justifiable?

Is it sustainable to have a minimum wage that has not increased in real terms in about 25 years? Have the deregulatory certainties of the 1990s been shattered by the global financial crisis, so much so that bankers - as Martin Wolff argues - are highly-paid public servants?

Labor’s recovery from the electoral abyss may not be swift; it may not be painless. But if the party’s history is anything to go by, getting the recovery right will be fundamental to its long-term future.