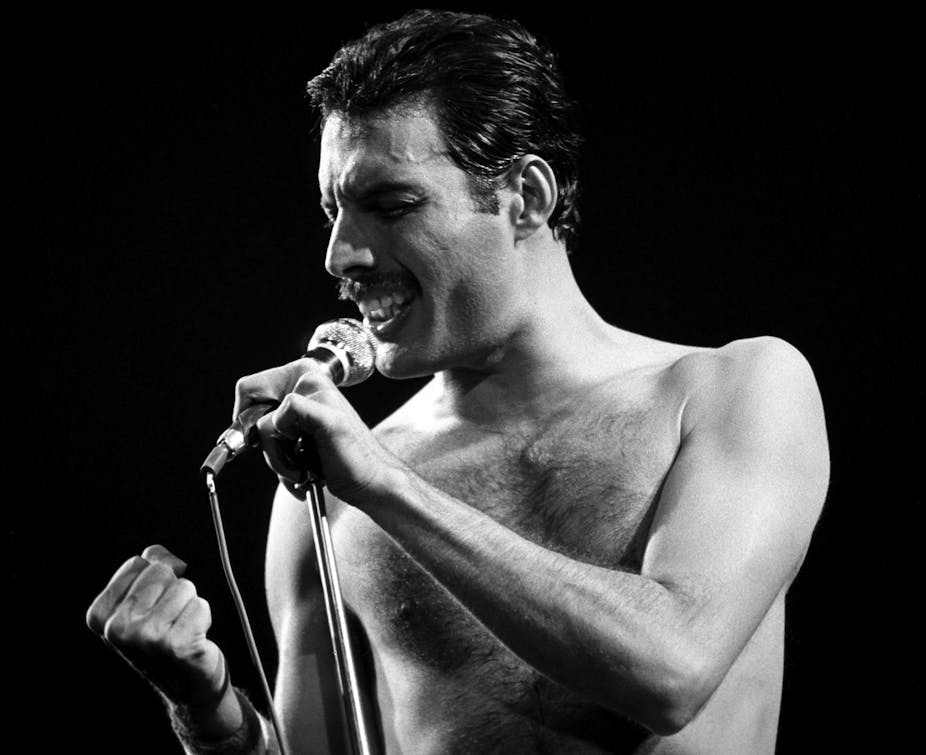

Millions of people tuned in to the Oscars to see “Bohemian Rhapsody,” the biopic of Queen frontman Freddie Mercury, compete for best picture, which “Green Book” ended up winning.

There were a lot of people cheering against “Bohemian Rhapsody.” The film has been dogged by accusations of homophobia, and the film’s director, Bryan Singer, was accused of rape and sexual abuse.

But as a gay historian, I keep coming back to something else – the tragic history that’s glaringly absent from this movie.

Mercury, along with all the other men and women who tested positive for HIV in the 1980s, was a victim not just of a pandemic but of the failures of his own governments and of the scorn of his fellow citizens. The laughable initial response to the HIV pandemic helped seal Mercury’s fate.

None of that is in the movie.

Governments turn their backs

In the early 1980s, when an epidemic of HIV first struck a few population centers in the U.S., U.K. and elsewhere, governments mounted almost no public health response.

Doctors initially noticed the virus in groups of people who happened to already be stigmatized for other reasons: men who had sex with men, drug users and, due to racism, Haitians and Haitian-Americans.

The prejudiced initial public health response assumed that many of these people were getting the virus because of whatever was already supposedly wrong with them. Gay men, the thinking went, were getting it because of “risky” behaviors like having lots of partners. HIV was not, therefore, a threat to most straight people. The medical profession’s view of HIV was so colored by the idea that it was intrinsically gay that at first they named the virus “GRID,” an acronym for “gay-related immunodeficiency.”

That was bad science, as we know now. Especially in the absence of good public health information about how to have safer sex, your risk of contracting any sexually transmitted infection goes up when you have more partners. But there was nothing about gay sex in particular that caused AIDS. Lots of straight people had multiple partners in the 1970s and 1980s, but initially, by chance, some communities of gay men were hit harder.

Governments and the general public quietly left people with HIV to their fate. As one activist pointed out, two years into the crisis, the U.S. government had spent more to get to the bottom of a series of mysterious poisonings in Chicago that killed seven people than to research AIDS, which had already killed hundreds of people in the U.S. alone.

The first report of HIV in the U.K. was in 1981. There was no test for the virus until 1985, and there was no really effective treatment until 1996. In 1985, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher tried to block a public health campaign promoting safe sex; she thought it would encourage teenagers to have sex, and, she claimed, they were not at risk of infection.

All told, it was an absurd response to the major public health catastrophe of our time and to a disease that would go on to kill 36 million people around the world – about as many as died in World War I.

Glossing over the era’s homophobia

All this left Mercury and other queer men in a terrible place. Without good public health information, and with research lagging, they were unnecessarily exposed to the virus. Diagnosed in 1987, Mercury didn’t live long enough for the development of antiretroviral combination treatment that could have saved his life.

He faced not just a deadly disease but vitriolic prejudice against people with HIV and AIDS. Two years before he was diagnosed, a Los Angeles Times poll found that a majority of Americans wanted to quarantine HIV-positive people; 42 percent wanted to close gay bars. As Mercury fought to keep making music as he grew sicker and sicker, the lead singer of the then-popular band Skid Row wore a t-shirt that said, “AIDS kills faggots dead.”

You won’t see this in the movie, either. No one in “Bohemian Rhapsody” is overtly homophobic; when homophobia appears at all, it’s in subtler forms. For example, a bandmate tells Mercury that Queen is emphatically not the openly queer disco act The Village People.

In real life, Mercury faced rampant homophobia – he never really came out publicly, and it’s easy to see why. In 1988, the U.K. passed a notorious anti-gay law that declared, officially, that homosexuality shouldn’t be promoted and that same-sex couples had “pretend” families, not real families. The law stayed on the books for over a decade.

The era’s glam rock and disco music scenes had queer moments, but it was all predicated on everyone being straight in real life. David Bowie told the press he was queer in 1972 and then loudly took it back in 1983, saying “the biggest mistake I ever made” was telling the press “that I was bisexual.”

The Village People were unique because they were unabashedly out and proud, but they weren’t a hit act because of that. They were a hit because the straight public either didn’t realize it or didn’t want to know.

Ask yourself: When you danced to “YMCA” at your high school talent show, did you know it was about gay culture? I’m going to guess the answer is no.

The same was true of Queen. How many of the rock fans who packed stadiums to see them play “We Are the Champions” knew that the heroic singer was not just a rock god, but a fabulous queer icon, too? Not many.

In the 1980s, Mercury ditched his glam rock look and cut his hair in a style popular in gay subculture, donning a black leather jacket and sporting an enviable, gorgeous mustache. Many fans hated it. In the U.S., they threw razors onstage.

No one to blame but himself?

When Mercury died in 1991, his bandmates felt it necessary to do a TV interview to dispute what the media was saying – that Mercury had brought AIDS upon himself with his decadent partying.

The movie also quietly makes it seem as if Mercury’s debauchery was to blame for his fate.

In the film, Mercury abandons the band to make a solo album in Munich with his diabolical boyfriend, who lures him into a shady queer world. His ex-girlfriend rescues him and he returns to the band. But by then, it’s too late: He has HIV.

In real life, Mercury didn’t break up the band, he wasn’t the first of the bandmates to make a solo album and, of course, partying doesn’t cause AIDS.

I hope someday, someone makes a better Freddie Mercury biopic, one that accurately depicts the historical moment he lived in and the challenges he dealt with. He deserves it.