Since announcing its arrival as a global force in June 2014 with the declaration of a caliphate on territory captured in Iraq and Syria, jihadist group Islamic State has shocked the world with its brutality.

Our series has been examining the historic and cultural forces behind the rise of these jihadists. Today, historian James Renton looks at the fateful 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement, which was pointedly denounced by Islamic State in the first video it released.

Ever since Islamic State (IS) spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani announced the establishment of a caliphate on June 29, 2014, analysts have been busy trying to explain its aims and origins.

Much of the discussion has concentrated on the IS leadership’s theology – an apocalyptic philosophy that seeks a return to an imagined pristine Islam of the religion’s founders. But this focus has led to a neglect of the group’s self-declared political aims.

For all the importance of religion in the way IS functions and justifies itself, we can fully understand the caliphate only if we pay close attention to the public explanations – the modernist manifestos – of those at the helm of its overall political purpose.

Viewed from this perspective, the caliphate appears primarily as an attempt to free the ummah – the global Muslim community – from the legacies of European colonialism.

The leaders of IS do not see their caliphate as an exercise in theocracy for its own sake, but as an attempt at post-colonial emancipation.

Looking right back

Certainly, the very name adopted by the declared leader of the caliphate suggests an acute preoccupation with a specifically religious mission that harks back to the early years of Islam.

Originally known as Ibrahim bin Awwad bin Ibrahim al-Badri al-Samarra’i (or variations thereof), he took on, long before the summer of 2014, the pseudonym Abu Bakr, the name of the first caliph (the successor to Muhammad as the religious and political leader of the ummah).

Ruling in the years 632-4, Abu Bakr put an end to dissent against the new Islamic system in its Arabian heartlands. He established the caliphate as an expansionist Muslim empire with military campaigns in, the sources suggest, present-day Syria, Iraq, Jordan and Israel-Palestine.

As a declaration of intent, this choice of name by IS’s leader – whose full moniker became, alongside the title Caliph Ibrahim, Abu Bakr al-Husayni al-Qurashi al-Baghdadi – seems to encapsulate much of what we need to know about the new caliphate’s ambitions.

Al-Adnani’s founding proclamation made a point of celebrating the military victories of the first decades of Islam and how the ummah then “filled the earth with justice … and ruled the world for centuries”. This success, he argued, was the result of nothing more than faith in Allah and the ummah’s adherence to the guidance of the Prophet Muhammad.

But the conquest of land and the establishment of a Muslim empire – or state, as those behind the new caliphate prefer to call it – is a means to a very specific end. It is not an end in itself.

Anglo-French infamy

According to al-Adnani, the caliphate is needed to take the ummah out of a condition of disgrace, humiliation and rule under the “vilest of all people”. Al-Baghdadi, speaking two days after he was pronounced caliph, was much more specific.

The fall of the last caliphate – and, with it, the loss of a state – led to the humiliation and disempowerment of Muslims around the globe, he said. And this condition of statelessness allowed “the disbelievers” to occupy Muslim lands, install their agents as authoritarian rulers and spread false Western doctrines.

Al-Baghdadi’s vague narrative refers to the story of the dissolution after the first world war of the Ottoman Empire, which had governed much of Western Asia for four centuries.

In its stead, the British and French empires took over significant parts of the region and remained for decades. When their rule came to an end, these colonial states did their best to leave behind successor regimes that would serve British and French interests and those of the wider West.

For IS leaders, these colonial machinations have left the ummah floundering ever since because they took away the essence of power in the contemporary world: sovereignty – territorially based political independence.

The caliphate is urgently needed, al-Baghdadi argues, to rectify this harmful absence. A similar argument for a caliphate, though made with a very different type of state in mind, was articulated by the UK-based scholar S. Sayyid in 2014.

The most explicit evidence of this political objective’s primacy is to be found in the new caliphate’s propaganda, which has been such an important part of the IS project.

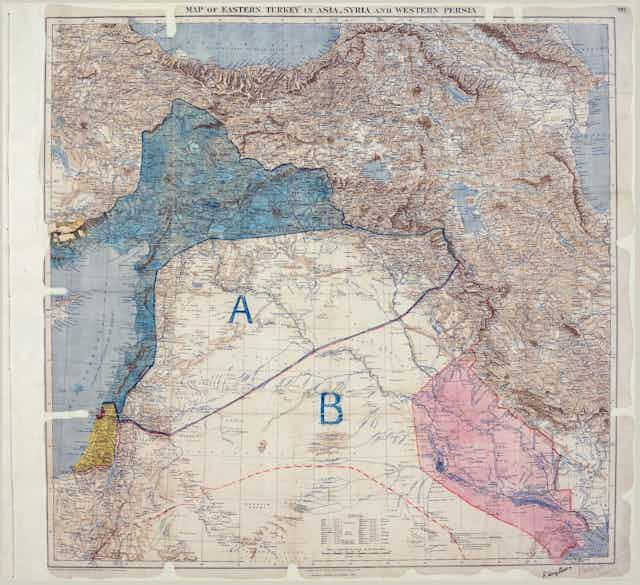

To coincide with the announcement of the caliphate, IS released a video entitled “The End of Sykes-Picot”. Signed in May 1916, the Sykes-Picot agreement was a secret Anglo-French plan for dividing the Asian Ottoman Empire into spheres of influence and zones of direct rule for the two European empires.

The Bolsheviks discovered the agreement in the Russian state archives soon after they took power in November 1917 and revealed its contents to the world.

The Sykes-Picot agreement

The Sykes-Picot agreement did not set out the borders of the states that replaced the Ottoman Empire, as the video suggests. But this error is beside the point if we want to understand the significance of the agreement for IS, and what it tells us about its caliphate.

In the Middle East, Sykes-Picot became shorthand for a whole narrative of Western betrayal and conspiracy in the region. But it also came to stand for the specific European colonial process of robbing the peoples of the region of their sovereignty.

And it is IS’s declared goal to undo this process. This is why “The End of Sykes-Picot”, above any other possible subject matter for an inaugural film, had to accompany the declaration of the caliphate.

For al-Baghdadi, sovereignty and Islam cannot be separated; thus the need for an Islamic state. He cannot use the term empire, even though it more accurately describes the global expansionist aims of his caliphate.

This is not just a question of semantics; it goes to the heart of the purpose of IS. The caliphate is needed, its leadership contends, to end the consequences of European empire, of colonialism. It is an effort to finally break away from the colonial condition; an attempt at a new post-colonial ummah.

Liberty from colonialism and sovereignty go hand in hand. The post-1918 world order embodied in the League of Nations and its successor, the United Nations, places the idea of sovereignty at the centre of how we understand power today. Within this system, the absence of a state is the absence of power.

The military defeat of IS and its loss of territory would, of course, make sovereignty, and thus the caliphate, impossible. But this defeat will not solve the problem of the sense of powerlessness that fuelled the 2014 caliphate in the first place; it will only compound it.

The real long-term challenge that faces opponents of IS, therefore, is not the overthrow of the caliphate – as difficult as that might be – or even to defeat “extremism”. It is, rather, to overcome the narrative at the centre of IS’s call to arms: Muslim alienation from the world system.

This is the seventh article in our series on the historical roots of Islamic State. Download our special report collating the whole the series.