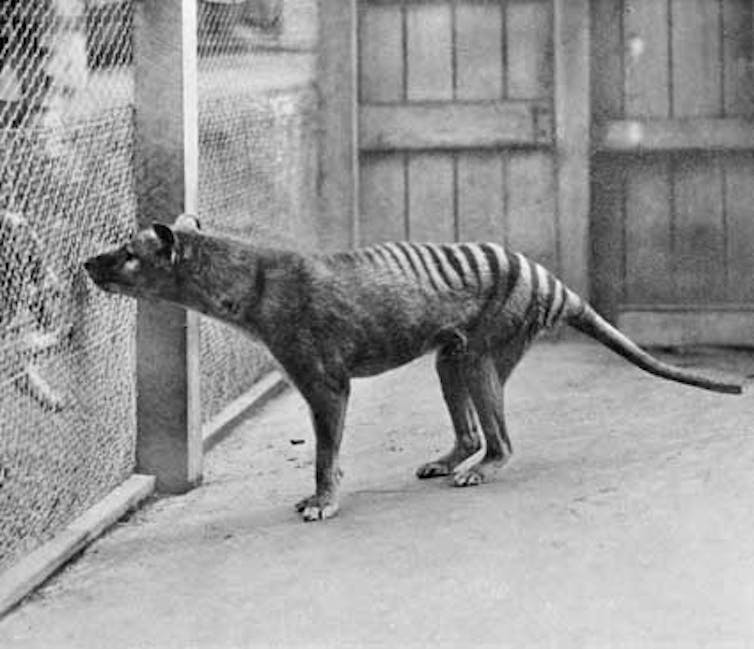

Among the most haunting and evocative images of Australian wildlife are the black and white photographs of the last Thylacine, languishing alone in Hobart Zoo. It’s an extraordinary reminder of how close we came to preventing an extinction.

That loss is also an important lesson on the consequences of acting too slowly. Hobart Zoo’s Tasmanian tiger died just two months after the species was finally given protected status.

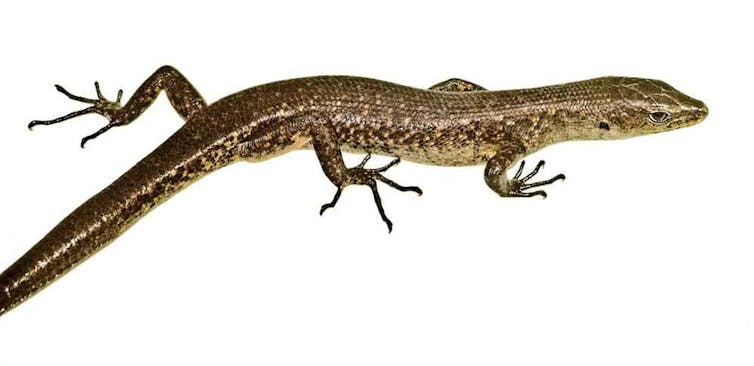

Last year, we wrote about the last-known Christmas Island Forest Skink, an otherwise unremarkable individual affectionately known as Gump. Although probably unaware of her status, Gump was in a forlorn limbo, hoping to survive long enough to meet a mate and save her species. It was an increasingly unlikely hope.

Despite substantial effort searching Christmas Island for another Forest Skink, none was found.

On 31 May 2014, Gump died, alone. Like the Thylacine, she barely outlived the mechanisms established to protect her, dying less than five months after being included on the list of Australia’s threatened species.

Sudden decline

Until the late 1990s, Forest Skinks were common and widespread on Christmas Island. Their population then crashed, and has now vanished. It has been a remarkable disappearance but not entirely peculiar, as it was preceded by an eerily similar pattern of decline and extinction (in 2009) for the Christmas Island Pipistrelle, the most recent Australian mammal known to have become extinct. Nor is the skink unique among the island’s native reptiles – most of them have shown similar patterns of decline.

We think Gump’s death is momentous because it probably marks the extinction of her species. If so, this will be the first Australian native reptile known to have become extinct since European colonisation – a most unwelcome distinction. (Unlike the death of an individual, extinction can be hard to prove. There are, after all, some optimists who believe Thylacines still live. For the Forest Skink, the trajectory of decline and the fruitlessness of dedicated searches provide reasonable grounds to presume extinction, although this conclusion may take some years to be officially recognised. And, of course, we’d like to be proved wrong.)

Lessons and legacies

Gump’s death might be passed over as a trivial bit of bad news and quickly forgotten. But Forest Skinks have been around since before modern humans walked out of Africa, so their extinction on our watch is not trivial. We should treat this loss with a profound respect, and seek to learn lessons that may help prevent similar losses in the future.

These are the legacies we seek from Gump’s life and death:

First, we should acknowledge that extinction is an unwelcome endpoint that is usually caused by ecological factors, but in recent times has often been compounded by deliberate human action or inaction. In most cases, extinction can be seen as a tangible demonstration of failure in policy and management, of inattention or missed opportunities.

In comparable cases elsewhere in our society, such as unexplained deaths or catastrophic governmental shortcomings, coronial inquests are instigated. Such inquests are widely recognised as a good way to learn lessons and to change practices in a way that will help avoid future failures. Inquests are also useful to acknowledge accountability, and to explain negative events to the public.

An inquiry – albeit more modest than a coronial inquest – is an appropriate response to any extinction. The presumed first extinction of an Australian reptile species would make for a worthwhile precedent: how could it have been averted, and what lessons can we learn?

Second, the Australian government has shown a welcome attention to the conservation of threatened species. It has appointed the first Threatened Species Commissioner, and federal environment minister Greg Hunt recently committed to seeking to prevent any more Australian mammal extinctions.

We would urge that this avowed interest be further consolidated by the loss of the Christmas Island Forest Skink, with a clear statement that this extinction is momentous and deeply regretted. The government should explicitly seek to avoid future preventable extinctions (a commitment recognised internationally through the Millennium Development Goals), and should pledge to implement a more effective and successful strategy for conserving Australia’s threatened species (and biodiversity generally).

Third, it is no coincidence that two endemic vertebrate species have gone extinct on Christmas Island in the past decade, and that many other native species are declining there, despite the fact that most of the island is a national park.

Christmas Island’s extraordinary natural values are not being matched by the resources provided to manage them, or by their low profile in our national awareness. The island meets the criteria to qualify as a World Heritage site, and it is time for the government to seek such a listing.

The fourth hoped-for legacy concerns the so far successful captive breeding program for two other Christmas Island species that otherwise would have gone the same way as Gump: the endemic Blue-tailed Skink and Lister’s Gecko.

This is an admirable accomplishment. But it is at best a halfway house, because a species solely represented by individuals in cages becomes an artifice. We urge the government to commit fully to a currently proposed conservation plan for Christmas Island that seeks to allow such species to return to their natural haunts, following eradication or effective control of their primary threats such as introduced black rats, feral cats, yellow crazy ants, giant centipedes and wolf snakes.

Fifth, this extinction has largely been enacted out of public view. With the exception of a 2012 scientific paper, the few reports documenting the Christmas Island Forest Skink’s decline are not readily accessible.

There is an island-wide biodiversity monitoring program (which is admirable), yet the results of such monitoring are not routinely reported or interpreted to the public. Our society deserves to be warned of impending and unrecoverable losses, and to know when good management has averted them.

This case is not unusual: for most Australian threatened species, it is difficult if not impossible to find reliable information on population trends. This makes it difficult to prioritise management, making it likely that management responses will be initiated too late, and it severely limits public awareness of conservation issues. We recommend the development of a national biodiversity monitoring program that would allow ready public access to information about trends in threatened and other species.

It is 78 years since the death of the last Thylacine. Our photographs of extinct Australian animals are now taken in colour, rather than black and white. But has anything else improved? We hope it will.