Gump has lived a cossetted life, nurtured in a cage on Christmas Island. Until last year, she had two acquaintances, but misadventure claimed them both.

Now there is only Gump. She’s the last known individual Forest Skink on Earth; as close to extinction as a species can possibly get, and her relative longevity is staving off, very temporarily, the final obliteration of a species that has probably lived for tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of years.

Hers is a salutary tale. Over the course of our lifetime, Forest Skinks have gone from abundant to absent across the rainforests of the 135 km2 Christmas Island. Eminent herpetologist Hal Cogger remembers witnessing (as recently as 1998) more than 80 individual Forest Skinks basking and foraging around a single fallen tree; until recent decades they were common and widespread across the island.

Then began a rapid and apparently inexorable decline. By 2003, they were confined to scattered pockets in remote parts of the island. By 2008, a targeted survey found them at only one remaining site. Now, recent repeated searches and trapping have failed: the species appears to have disappeared completely from its natural haunts.

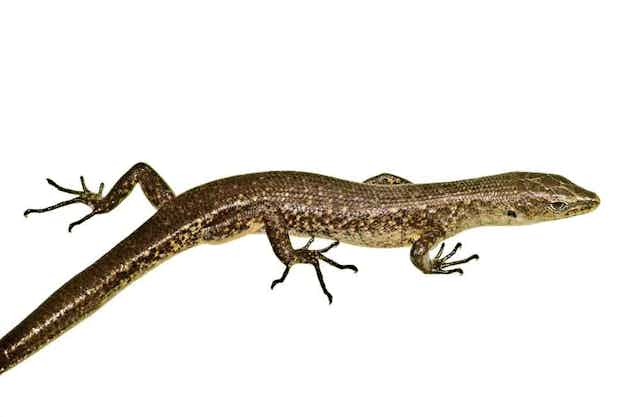

The Emoia skinks to which the Forest Skink belongs are a large group (of more than 70 species), with marked radiation on islands in the Pacific. Most, including the Forest Skink, are moderately large, thickset, active during the day and ground-dwelling. The Forest Skink is relatively nondescript: largely unpatterned, chocolate-brown, about 20 cm long (of which about two-thirds is tail). A recent genetic analysis has concluded that the Forest Skink is the most ancestral of the genus.

Status

The decline and imminent extinction of the Forest Skink has outpaced its recognition as a threatened species. Indeed, notwithstanding its looming extinction, it is not yet listed as threatened under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act, although it is likely to be so soon. This is as much an illustration of the shortcomings in the official listing process as it is of the speed of the skink’s decline.

The Forest Skink shares its plight and pattern of recent decline with most of the small set of native reptiles on Christmas Island. The Coastal Skink (Emoia atrocostata) has almost certainly declined to extinction on Christmas Island (but is still considered to persist elsewhere), the endemic Blue-tailed Skink (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) is probably now extinct in the wild (but more happily than for the Forest Skink, a functional captive breeding population has been established), the endemic Lister’s Gecko (Lepidodactylus listeri) is very nearly extinct in the wild (but has a captive breeding population), and the status of the Christmas Island Blind Snake is unknown (with only a single individual reported over the last two decades). Oddly, the other endemic species, the Christmas Island Giant Gecko (Cyrtodactylus sadleiri), has remained somewhat common, but has still suffered a significant - though unmeasured - decline.

Threats

One of the intriguing but frustrating issues in this case is that the cause or causes of the decline remain unresolved. This applies to Christmas Island’s other native reptiles, and perhaps also for the better known and remarkably parallel case of the Christmas Island Pipistrelle.

There are plausible suspects, most notably predation by the non-native Yellow Crazy Ant, Giant Centipede or Wolf Snake; competition with the five non-native reptile species; poisoning by insecticides used to try to control the crazy ants; and disease. There is no conclusive evidence for any of these factors, and it is now too late to decipher the clues and manage the threats for this species.

But, it is not yet entirely too late for the two other highly threatened Christmas Island lizard species that are held in captivity, and ongoing research with them may allow an informed post-mortem conclusion about the extinction of the Forest Skink.

Strategy

Sadly, there is little future for the species. Its sole living representative will most likely die within the next couple of years. Over the last two years, there have been some dedicated searches for additional individuals, but these have proven fruitless. In the years immediately preceding, there were a few sightings and near misses of capture; tantalising but unrealised opportunities. In those failures, the survival of the species may have slipped through our fingers.

Just possibly, we are too pessimistic. It may be that there remain a few secretive Forest Skinks that have not yet succumbed to whatever nemesis it is that haunts their lives. There may yet be time, albeit very limited time, for the optimistic to invest in a more comprehensive search that could yet find a mate for Gump, and buy more time to forestall the extinction.

An advisory group for Christmas Island’s reptile species has been established, and captive breeding (on Christmas Island and at Taronga Zoo) has provided hope for two of the other threatened reptile species.

Conclusion

Failure is a good teacher. This is an extinction that ought not to have happened. There are clear lessons:

Declines can be very rapid and, without quick response, rapid declines are likely to lead to extinction.

The current process for listing threatened species is inadequate, though a listing process that fails to produce resources to identify and ameliorate the causes of the listing has limited value.

Early intervention, such as through captive breeding, may provide an irreplaceable opportunity for conservation.

Island biotas may be extremely susceptible to extinction and they need protection with adequate biosecurity measures.

It may be damnably difficult to identify critical factors that drive declines and extinctions.

Individually, Gump is an undistinguished and inconsequential lizard, but she has now become a talisman, marking the finality and proximity of extinction. Extinction is a chain, and the last link of the chain is the death of the last individual.

The Conversation is running a series on Australian endangered species. See it here.