How much would you give up to have a home that didn’t cost you a cent in energy bills? Would you sacrifice that spare bedroom that’s full of junk and hardly gets used? Or the additional bathroom? What about the second TV room?

As the credit card bills start to arrive after Christmas, many of us often resolve at the start of a new year to manage our money a bit better. And if you’re looking for somewhere to start, there’s no place like home.

Whether you’re in the market for a brand new home, or thinking about expanding the home you’re already in, our research has shown just how much size matters when it comes to Australians’ cost of living.

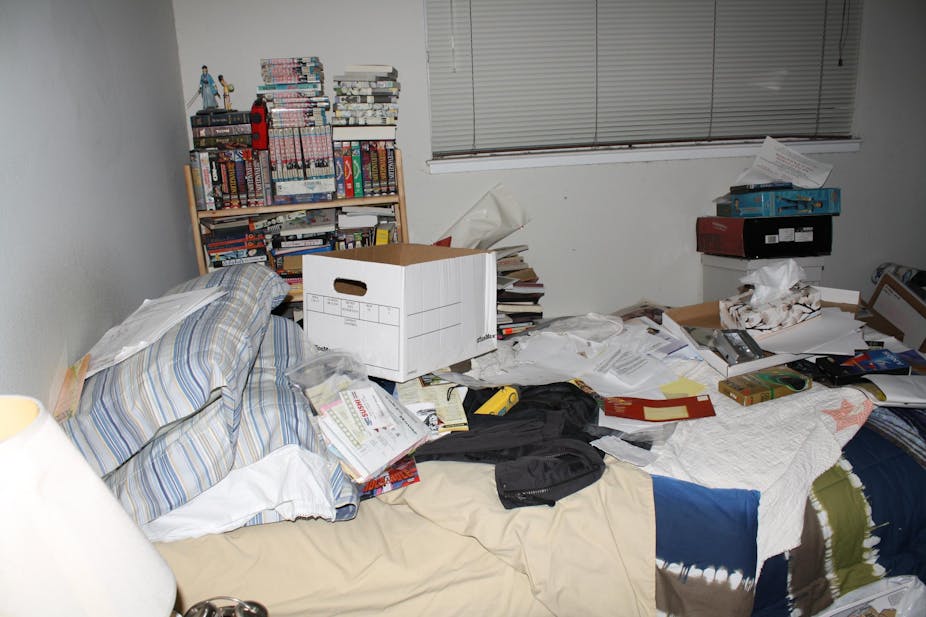

Expensive spare rooms

On average, Australian homes are among the biggest in the world. And our houses increasingly have more and more rooms.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics has found that 78% of Australian houses have more bedrooms than are needed to accommodate the occupants, based on an internationally-applied Canadian standard. That number is even higher among home owners, rather than renters (see the ABS graph below).

For new home buyers, slightly decreasing the size of their home - the equivalent of losing that spare bedroom - would be enough to pay for improved environmental and energy performance of the house.

This would slash energy bills, improve cost of living and dramatically reducing the household’s environmental impact.

A small loss for a big gain

Drawing on our recent research, an average size (250 metre square) new 6-star home in Victoria now costs $195,000, excluding land, and has $1700 of annual energy running costs.

Yet we found that if you reduce the size of that average home by 5-10% to 225-235m2, the $20,000 you would save on upfront costs would be enough to offset most, if not all, of the costs for energy efficiency improvements and renewable energy (such as solar photovoltaic panels) to mean it had no net energy needs.

In talking about a home with zero net energy needs, we mean that one that is producing enough energy on-site to meet its ongoing operating needs, and resulting in no ongoing energy costs for the household.

To achieve zero net energy performance, there is significant upfront cost, which typically means that it is seen as “unaffordable” for the average family. However, there is a simple way of covering these upfront costs: build smaller.

Smaller floor space would not necessarily mean the house would feel smaller. We found an example of a sustainable design and construction company in Canberra which ran a workshop to ask potential clients what they wanted in a house, within the limits of building an environmentally sustainable and affordable 200m2 house. They found that as long as they got the key areas right, such as a nice entertaining area connected to the outside, they could trim some floor space from other rooms and even remove some additional rooms all together.

Building now for the future

There has been a steady increase in the average floor area of new homes between the mid-1980s and 2012-13.

The size of new houses increased from 162.4m² to 241.1m² (a rise of 48.5%), while new other residential dwellings (such as units or townhouses) increased from 99.2m² to 133.9m² (a 35.0% increase).

While the most recent ABS figures show that house size has declined slightly since a peak in 2008-09, the dominant trend of the past 30 years has been that bigger was better.

And we need to remember that once built, housing can last many decades, locking in future occupants to a higher cost of living.

There are a number of direct and indirect approaches which could be introduced or driven by the government to encourage smaller housing.

For example, the government could mandate that homes should not overshadow their neighbours and block out their access to sunlight, which would affect their ability to generate power from solar panels.

There are also more subtle indirect measures that could be applied. For instance, banks could rethink their financing models for home loans to take into account the cost of living in a home (such as bigger energy bills for less energy-efficient homes) and homeowners’ ability to repay those costs when weighing up someone’s capacity to pay off their mortgage.

But, unless the government takes action, ultimately it’s up to us as consumers to think about whether we’re happy to keep paying higher costs for bigger homes with rooms to spare. If not, you do have a choice.

With a huge population of baby boomers looking to downsize, and Gen Y’s preference for smaller, low-maintenance housing located near work and amenities, it’s just possible that higher quality, more sustainable smaller housing could become more common.