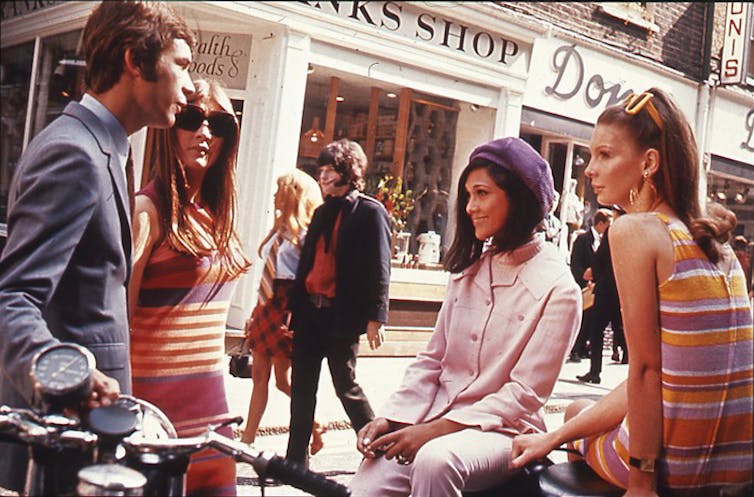

Dressed in a mini skirt and passionate about boys, music, dance and fashion, the 1960s teenage girl is a pop culture icon, the seeming beneficiary of the ascendancy of mass youth culture in the west and of unprecedented social and cultural changes.

Quite how real women actually experienced – and benefited from – this era of social change is more complex. For the past six years, I have led the first detailed study of girls growing up in Britain between the 1950s and 1970s. In order to understand how this era has shaped women’s experiences and identities in later life, my colleagues and I conducted interviews with 70 women born between 1939 and 1952.

We also explored data on girlhood from Britain’s first birth cohort study, as well as the English longitudinal study of ageing.

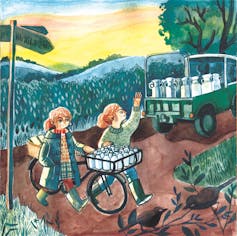

The current Teenage Kicks exhibition, on show at the Glasgow Women’s Library and online until May 18, delves into eight of our interviewees’ stories. Edinburgh-based artist Candice Purwin has illustrated the striking diversity they relay: girls growing up in very different circumstances navigated the possibilities and pitfalls of the 1960s and early 1970s in very different ways.

Swinging London

Our interviewees were from different social class backgrounds and across both rural and urban locations. To spark memories, we played music that these women would have listened to when they were young. We talked with them about their personal photos.

One interviewee, Liz, was the epitome of a modern, mobile, young woman. At 17, she was earning an income, travelling to Europe with friends and enjoying the consumerism of swinging London. She told us about visiting clubs and shopping in new department stores. At 19, she left to work in the US.

This sense of London as a place of opportunity was a recurrent theme. Andrea embarked on a science degree in London, aged 18. Coming to the capital meant being able to escape village life and the scrutiny of her religious parents.

Andrea found freedom to engage in student politics and to come out as a lesbian. Being gay was a stigmatised identity at the time. She recalled furtive visits to London’s only lesbian club, the Gateway Club. “A crummy place really,” she said, “down in the basement, small, hot and dark.”

Another interviewee, Joyce, grew up in poverty in an overcrowded home in central London. She said she felt like “the bee’s knees” when she started earning money. She described the pair of white boots she was able to buy, to wear when she went out dancing.

Like her peers, though, Joyce mainly spent her leisure time walking the streets with friends and going to cafés. “We sat there all night with one coffee,” she said, “sometimes two, if you were feeling rash.”

In rural areas, girls were often dependent on limited public transport to access leisure venues, shops and cafes in nearby towns. Going to the cinema was a major expedition.

Valerie, who grew up on a farm near Portsmouth on England’s south coast, said: “We couldn’t get there until 6 o’clock and we had to be on the 9 o’clock bus back.” As films were often shown on a continuous loop throughout the day, she said “you’d pick up a film half way through, watch it until the bit that you came in at, and then leave.”

For girls abroad, the capital represented the opportunities Britain itself promised. One interviewee, Cynthia, migrated from St Kitts, in search of better prospects. “Jobs were easy to find when I came to Britain,” she said.

Cynthia worked as a machinist in a clothing factory by day. By night, she studied typing and administration. These new qualifications helped her secure a better-paid job as a secretary in a solicitor’s office.

Unequal access

We found that access to the widening educational and professional opportunities for girls was uneven. More were going to university and into professional training. Most, however, left school at 15 without qualifications and with limited work prospects.

Joyce thrived at school but left at 15 when her mother became ill. Later, she took evening classes and became a telephonist.

Pamela too was a star pupil but her mother thought it pointless educating a daughter. “She’s only going to get married!”, her mother would say. Once in the workforce, however, Pamela excelled and quickly progressed into management.

Like others whose education was foreshortened due to hardship and sexism, Pamela and Joyce later regretted not having been able to pursue their studies further.

In popular culture, the 1960s are associated with growing permissiveness. Most of the women we spoke with, however, said that, as girls, they feared getting pregnant out of wedlock.

The pill became available to married women in 1961. But access for single women was restricted until 1974. Even access to basic sex education was limited.

Pamela fell in love at 17 and got pregnant. Her mother insisted that she give up both that relationship and her baby. She eventually started a new relationship and married at 20. This was an abusive marriage. Taking control of her fertility, she went on the pill and by age 24, she had secured a divorce.

The unprecedented trend towards early marriage meant youth was typically short-lived. In 1965, 40% of brides were under 21. Easier access to divorce from 1969 proved an important development for many.

Women speak about aspects of their younger selves having stayed with them in later life. Many live with what we call “shadow selves”, the feeling that they could have been a different person and had a different life if things had gone differently when they were young.

Some of our interviewees explained that it was not possible to rectify what they missed in their youth. Others spoke about using retirement to make up for missed opportunities. Most advise their own children and grandchildren to make the most of being young.