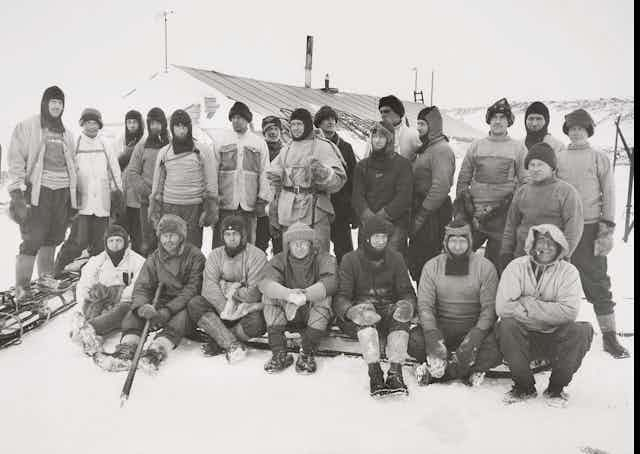

The icy continent has historically been a place for men. First “discovered” in 1820, Antarctica would not be visited by a woman for well over a century.

In 1935, Norwegian Caroline Mikkelsen, a whaler’s wife, became the first woman to do so, some 24 years after her compatriot Roald Amundsen had trekked all the way to the South Pole.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that women were finally allowed to participate in Antarctic science.

How had Antarctica come to be so dominated by men? Where were all the women?

In 2016, one of us (Meredith) took part in the largest non-scientific expedition of women to Antarctica in history.

Among the group were 77 women working in Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, and Medicine (STEMM), who took part in a three-week leadership program. As part of our study of this program, Meredith travelled with the group to Antarctica to gather women’s first-hand accounts of their experiences.

During the expedition, Meredith was reminded of the work of the author and environmentalist Carol Devine, who has been doing a mapping project that has found more than 200 places in Antarctica named after women.

As Devine wrote in 2017:

I was looking at the Antarctic map on [the] wall. There it was, “Marguerite Bay”, a dip in the port side of Antarctica’s tail. Aha, I thought, so there were women here, at least symbolically, ages ago…

Who was Marguerite? Her name reached the Antarctic because her husband, Dr Jean-Baptiste Charcot, leader of the French Antarctic Expedition, discovered a bay and named it for her in 1909. There she was, symbolically, as were many of the other women to Antarctica — names on maps.

The portrayal of Antarctica as a female body that must be mastered and penetrated by men is central to Heroic Era narratives of the continent. Given this framing, it is unsurprising women were long denied access to Antarctica.

Many polar institutes around the world have traditionally justified the exclusion of women by arguing there were no facilities such as toilets for them on stations.

It certainly wasn’t due to a lack of interest. In 1914, three British women named Peggy Pegrine, Valerie Davey and Betty Webster wrote to Ernest Shackleton to apply for his next expedition. They described themselves as “three sporty girls” and offered to wear men’s clothes if there were no suitable female ones available. They added:

…we do not see why men should have all the glory, and women none, especially when there are women just as brave and capable as there are men.

Shackleton’s reply noted his “regrets there are no vacancies for the opposite sex on the expedition”.

Coming in from the cold

Mikkelsen became the first woman to set foot on Antarctica in 1935. But it was not until 1956 that women began to be properly involved in Antarctic science.

Russian geologist Maria Klenova landed in Antarctica to make the first Soviet Antarctic Atlas. Women were finally charting maps, rather than just having their names written on them.

In 1969, an all-female group of US scientists led by Lois Jones landed in Antarctica. They wanted to collect their own samples from the McMurdo Dry Valleys — something they had so far been prevented from doing.

Pointing to the anxiety and scepticism surrounding the voyage, the New York Times described the expedition as “an incursion of females” into “the largest male sanctuary remaining on this planet”.

Read more: How to keep more women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM)

From the 1980s, the Australian Antarctic Program and the British Antarctic Survey allowed women to stay on research stations and conduct land-based Antarctic fieldwork.

Today, women are more fully integrated into National Antarctic Programs and women often lead field teams. Nearly 60% of early career researchers in polar science internationally are women.

Yet while women’s participation in the Australian Antarctic Program is increasing, women still comprise only 24% of expeditioners. Women make up 33% and 30% of US and UK Antarctic expeditioners, respectively.

These low numbers are tied to the fact that women still face a range of barriers in a polar science career and especially during fieldwork, including:

gender bias and discrimination

caring responsibilities

lack of recognition such as prizes and awards

physical barriers, such as field gear not being available in women’s sizes.

Why does this matter?

Antarctica is strategically important to Australia and many other nations. Yet the credibility of Australia’s Antarctic leadership is at risk without a substantial commitment to diversity and inclusivity.

Existing power relations may prevent women and those from other underrepresented groups (such as people of colour and LGBTIQ+ people) from participating, or even considering, the possibility of an Antarctic science career.

Equity and inclusion in Antarctic science will not come about simply by waiting for more women to volunteer to become expeditioners.

Here is how we can proactively promote inclusion:

Change the image of a polar scientist. The “typical” polar scientist is still assumed to be a straight, white man who works for many months away in Antarctica. Yet polar scientists work in a range of settings. In fact, many polar scientists work indoors at a computer!

Grow the leadership pool. National Antarctic Programs must develop targeted recruitment campaigns, gender-neutral hiring practices, awareness of unconscious bias, training to be an “upstander” rather than a bystander, and parental leave policies and flexible work arrangements that can facilitate a woman’s ability to succeed in polar science.

Women are in Antarctica to stay. They play important roles in the scientific, logistical and managerial realms of Antarctic operations.

Making polar research more inclusive will enrich the diversity of the scientific community and have flow-on effects for the quality of Australia’s Antarctic science.

CORRECTION: The original version of this article failed to give correct credit to Carol Devine for the story of the discovery of Marguerite Bay. This has been amended.