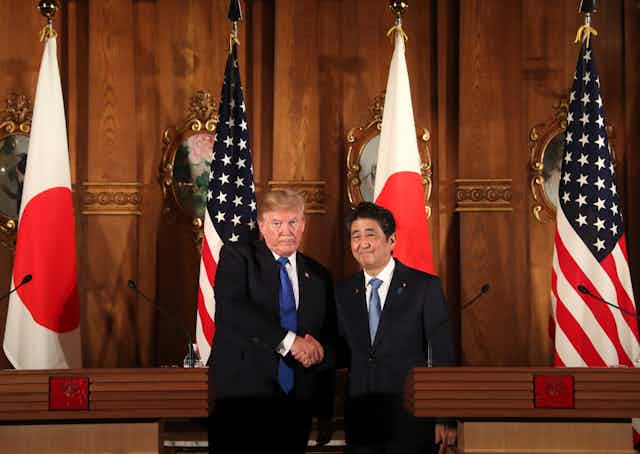

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will meet with President Donald Trump at Mar-a-Largo on April 17 and 18.

The relationship between these two leaders’ countries may help shape the U.S. approach to upcoming talks with North Korea. Those talks will likely be focused on denuclearization and regional stability.

The U.S.-Japan relationship since World War II has rested on economic and military cooperation. It is sustained through a complex network of institutions that facilitate interactions between the two countries. But interactions among U.S. and Japanese citizens themselves – a form of “soft diplomacy” – also play an important role in furthering relations between the two countries.

Since 1987, the Japanese government’s Japan Exchange and Teaching Program has built familiarity with and interest in Japan among young Americans and citizens of more than 60 other countries. The program brings young college graduates to work in Japan for at least one year. It has helped sustain a bilateral relationship that the U.S. Department of State describes as key to stability and prosperity in Asia.

I am an alumna of the exchange program and recently published a book about its growing importance to the U.S.-Japan relationship. I argue that through the program, Japan has nurtured a generation of Americans who function as “willing interpreters and receivers,” or citizen ambassadors, for Japan at home and abroad.

Beyond teaching English

For 30 years, the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program has recruited college educated Americans to live and work in Japan. This year, there are 2,924 Americans in the program.

Tomohiko Taniguchi, a key adviser to Japan’s prime minister, summed up the program to me as “the single most shining crown jewel of Japan’s diplomacy.”

Participants either teach English or help organize events such as theatrical performances, international conferences and sports exhibitions across Japan’s small towns and regional capitals. Over the course of its history, more than 30,000 Americans have participated. That’s over half of the 60,000 alumni worldwide.

The three core goals of this exchange program are increasing foreign language proficiency among Japanese citizens, nurturing an international mindset in Japanese communities and, on the flip side, improving global attitudes toward Japan.

The program has gotten significant criticism for failing on the first of these goals. English language proficiency in Japan has not improved since the program began. During Japan’s 2010 budget talks, this problem nearly sank the program’s government support.

No formal study has evaluated the program’s success in promoting broadened worldviews among the Japanese. Meanwhile, my research has focused on the third goal. Has the program affected how participants – especially alumni in the United States – feel about Japan?

Part of the fabric

Based on my surveys and interviews with alumni, meetings with program sponsors and input from experts on U.S.-Japanese relations, I have found the majority of U.S. alumni maintain interest in and affection for Japan.

Today, alumni of the program work in federal agencies, state and local governments, major educational institutions, leading media outlets and the nonprofit and private sectors. More than 100 American alumni work for the U.S. Department of State.

Following Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami, the State Department asked foreign service officers worldwide who were familiar with the country’s language and culture to assist with consular work (serving American citizens in Japan and processing visa applications for Japanese citizens seeking to travel to the United States) as well as with relief efforts. Dozens of alumni in the diplomatic corps answered the call, joining other alumni who were already serving at the U.S. Embassy and consulates across Japan. Indeed, alumnus Matthew Fuller was already there serving as special assistant to the American ambassador to Japan, John Roos.

In a tragic side note, of the more than 16,000 people who perished in the disaster, the only two Americans who died, Taylor Anderson and Monty Dickson, were participating in the exchange program.

Other American alumni also sprang into action in the disaster’s aftermath, raising more than US$360,000 for relief efforts. An online community run by alumni served as a clearinghouse for information about how to help. The New York alumni chapter coordinated the collection and dissemination of donations.

Japan scholar and Professor Emeritus at Columbia University Gerald Curtis described to me an “unanticipated benefit” of the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program: It has produced a “generation of Americans and others who are connected to Japan.” He compared it to the U.S. government’s recruitment and training of Japan experts during World War II.

Alumnus Michael Auslin has documented how that wartime generation of Americans went on to careers in academia, journalism and government. They influenced the U.S.-Japan relationship for decades thereafter. They taught students at American universities about Japan, reported about Japan in U.S. media, and served as experts within the U.S. government.

The Japan Exchange and Teaching Program gives Americans a chance to learn more about Japan. In fact, one Japanese diplomat told me JET alumni are tough negotiators when they represent the U.S. in bilateral talks with Japan because “they know us so well.”

Thanks in part to Japan’s sustained investment in the program, tens of thousands of Americans support this friendship between two countries, whose interactions are critical to continued peace in a region facing many challenges.