The bulwark of Kenya’s democratisation is the rule of law – specifically the implementation of the 2010 constitution. The supreme law, which was only realised after a protracted struggle, provides for vertical and horizontal checks and balances.

But, as my research shows, a cohort of reactionary politicians - beneficiaries of the one party autocracy which ended in 1991 – have repeatedly set about undermining these checks and balances. They have done so by hollowing out the legislature, judiciary, office of the Attorney General and independent oversight bodies.

Even county governments, the second tier of government, face interference, including militarisation by President Uhuru Kenyatta who is inclined to centralising power.

Throughout the one-party dictatorships of Jomo Kenyatta and then Daniel Moi, arbitrary amendments and disregard for the founding constitution that was in place at the time – also known as the Lancaster constitution – entrenched impunity and flagrant disregard for the rule of law without sanction.

This placed Kenya on a perilous path of tribal acrimony, institutionalised impunity and state violence.

A bumpy road

Amendments to the old constitution were self-serving and scornful of the doctrine of separation of powers. Kenyatta (1963-1978) effected 13 fundamental amendments to consolidate power in the executive.

His successor, Moi (1978 - 2002), legally abolished multiparty politics and constrained the political space further. Another of his amendments removed the tenure of judges. This eroded judicial independence by placing the judiciary under executive control. Mwai Kibaki (2002-2013) stonewalled constitutional reform, squandered a moment of national rebirth and pushed Kenya to the precipice in 2007.

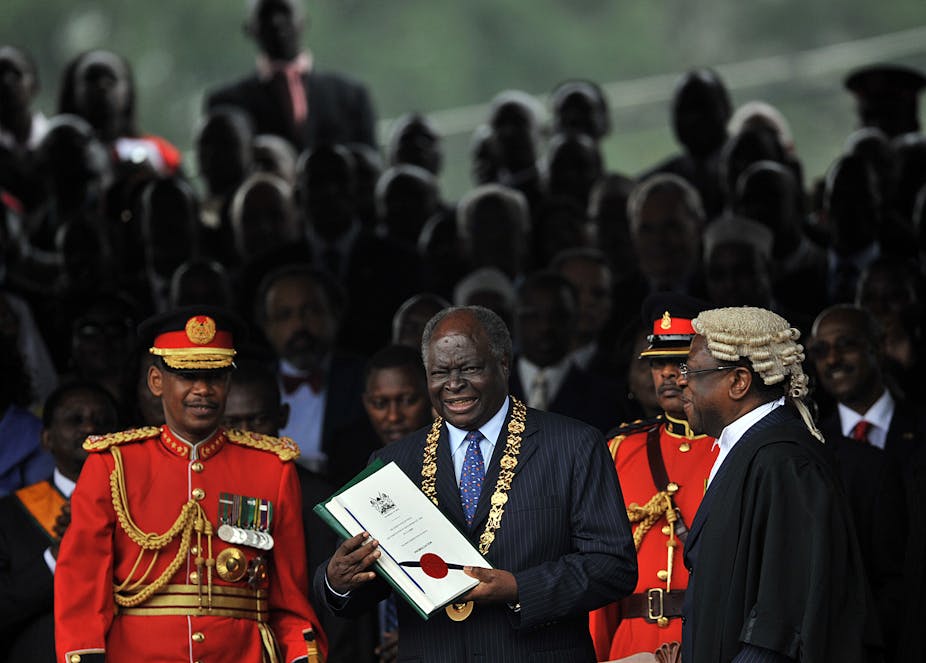

But in the last decade Kenya has made strides towards democratisation, particularly in the aftermath of the violently disputed elections in 2007. That election exposed Kenya’s fragile democracy, underscored the indispensability of a rules-based politics and forced erstwhile political rivals to close ranks in the enactment of the 2010 constitution.

Yet the spirit of the constitution is yet to find traction. This is a concern that the Law Society of Kenya has raised. It has accused Uhuru, son of Jomo Kenyatta, of trifling the constitution and even called for his impeachment.

Subsequent elections have not affirmed Kenyans’ confidence in participatory democracy. In each of the three elections held under the 2010 constitution, bigotry and fraud upstaged policy. Elections held in 2013, and twice in 2017, were marred by boycotts, violence and rigging.

A prerequisite for Kenya’s democratic renaissance is leadership that is immersed in the national values that are contained in the constitution. Kenyan politicians, beginning with Kenyatta, must submit to constitutionalism – a morally binding fidelity to the rule of law – to infuse trust in the society and confidence in state institutions. The current political climate does not provide much room for optimism since rogue politicians are not sanctioned. This has led to endemic impunity.

Democratic reversal under Uhuru Kenyatta

Kenyatta’s regime epitomises unsavoury attributes such as impunity, malfeasance, cronyism, corruption, nepotism and tribalism. There are a number of examples that can be cited. For example, the president routinely disregards court orders.

Kenyatta has also been accused of ethnic bias. His political appointments are tribal and nepotistic. This is in defiance of meritocracy and Kenya’s diversity.

It can reasonably be argued that Kenyatta is rolling back democratic gains. He is doing this, for example, by trampling on the Bill of Rights and the doctrine of separation of powers. Through his latest executive order, he’s purported to place the judiciary and independent constitutional institutions under the executive.

The bicameral parliament is no more than a rubber stamp of executive decisions, a throw back to one party dictatorship.

And Kenyatta holds political party meetings at State House. This conflates party and state to recreate an autocracy.

Politicians, such as Raila Odinga, who previously stood up against dictatorship, have morphed into apologists of the establishment. The rapprochement between Kenyatta and Odinga, arguably Kenya’s foremost tribal barons, has alienated the populace.

Read more: Rapprochement between two leaders isn't enough to fix Kenya's deep divisions

The supposed centrepiece of this two-man pact is constitutional reform. The intent is to expand the executive and create more positions ostensibly for ethnic inclusivity. Yet the process is opaque. It cynically reduces inclusiveness to spoils politics and self-preservation.

State of affairs

A state is sovereign to the extent that it exercises authority in trust of the people, provides public goods, upholds basic rights, and inspires obedience. Put simply, a sovereign state is responsible and accountable.

But Kenya’s current leadership has further eroded the legitimacy of the state.

Plurality of views, contestation of ideas, and dissent are the lifeblood of democracy and transformation.

But these are being stifled in Kenya for sycophancy.

The executive has consistently reified tribalism and neutered those fighting against abuse of power. Dissenters have been co-opted, purged or silenced and are, therefore, unable to mobilise along crosscutting concerns, or to push back against executive overreach.

In addition, selective application of the law has politicised the criminal justice system. Injustice desecrates life, stirs tribal animosity, and could easily precipitate state collapse.

Political parties in Kenya are mere reservoirs of tribal votes. Elected and nominated parliamentarians are at the beck and call of tribal barons and beholden to self interest. Supporters, hardly party members, are commodities who are callously auctioned off to the highest political bidder.

Meanwhile, the 2010 Constitution is a watershed document. It was supposed to provide a framework for good governance and to rejig the polity. Instead, it has become a battleground for supremacy wars.

Glimmer of hope

But there is a glimmer of hope amid the cynicism. Chief Justice David Maraga has unstintingly asserted the sanctity of the constitution with a remarkable conviction. He recently condemned the president for disobeying court orders and treating the judiciary as if it were an appendage of the executive.

The constitution is not responsible for Kenya’s fractious politics and state excesses. Impunity is. Kenya’s democratic gains must be safeguarded.