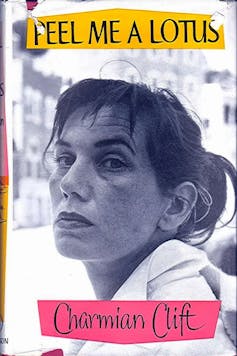

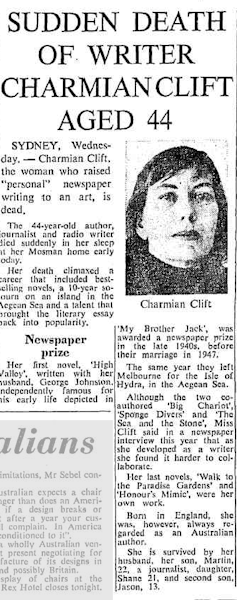

Fifty years after her death, Australian writer Charmian Clift is experiencing a renaissance. Born in 1923, Clift co-authored three novels with her husband George Johnston, wrote two under her own name, produced two travel memoirs, and had weekly column widely syndicated to major Australia papers during the the 1960s.

Clift has long been overshadowed by the legacy of Johnston, whose novel My Brother Jack is considered an Australian classic. Her novels and memoirs are sadly out of print, yet she is increasingly recognised for her important place in Australian culture.

In 2018 she, along with Johnston, was inducted into the Australian Media Hall of Fame in recognition of her work as a columnist. She is also being reimagined in fiction, as the subject of A Theatre of Dreamers (2020), a forthcoming novel by English author, Polly Samson, and in Tamar Hodes’ The Water and the Wine (2018).

The revival of interest in Clift is more than a collective nostalgia or feminist correction of the historical record, although both are relevant. Many of her readers from the 60s still remember her newspaper column, and the impact that it had on their view of Australia’s place in the world, with great affection.

Younger generations, particularly women, have also been exposed to Clift’s clear and passionate voice after the columns were published in several volumes in the years following her death. That Clift and her writing continue to resonate with contemporary Australia tells us something about both her and the nation.

The Hydra years

Much of the renewed interest in Clift is focused not only on her writing, but also on the near decade that she and Johnston lived on the Greek Island of Hydra. In late 2015, artist Mark Schaller’s Melbourne exhibition, Homage to Hydra, featured paintings depicting Clift and Johnston’s island lives, with several featuring other residents from Hydra’s international population of writers and artists, including Canadian poet and songwriter, Leonard Cohen.

The same year, Melbourne musicians Chris Fatouros and Spiros Falieros debuted Hydra: Songs and Tales of Bohemia, marrying Cohen’s songs to a narrative about Clift and Johnston’s time on Hydra.

Read more: Friday essay: a fresh perspective on Leonard Cohen and the island that inspired him

In 2018, our book, Half the Perfect World: Writers, Dreams and Drifters on Hydra, 1955-1964, told in detail of the fabled decade of Clift’s life as a bohemian expatriate.

To date in 2019, Sue Smith’s play, Hydra, has been staged in Brisbane and Adelaide, casting Clift in ways that resonate sympathetically with the concerns of contemporary audiences. As Smith writes in her script’s introduction:

Charmian was a woman ahead of her time. We see this in the choices she made both in her personal life, whether it be scandalising the Greek locals by wearing trousers and drinking in bars, to insisting upon her personal and sexual freedom and, of course, through her work.

Read more: Sue Smith's Hydra: how love, pain and sacrifice produced an Australian classic

‘Charm is her greatest creation’

Modern readers might respond to Clift the writer, but the focus on her years on Hydra suggests there is also great interest in her charismatic personality and tempestuous life with Johnson, as their dream of a cheap and sun-soaked creative island life slowly soured.

While researching the couple’s lives on Hydra, we came across a suggestive, eye-witness diary entry by a fellow writer, New Zealander Redmond Wallis, written in 1960.

Charm is her greatest creation, Charmian Clift, the great Australian woman novelist. Charmian is very curious. She is, potentially at least, a better writer than George but she has and is deliberately creating a picture of herself … which one feels she hopes will appear in her biography some day.

The head of a literary coterie, beautiful, brilliant, compassionate but still the mother of 3 children, running a house. Sweating blood against almost impossible difficulties – a husband inclined to unfounded jealousy, the heat, creative problems, the children, the problems foisted on her by other people … and yet producing great art.

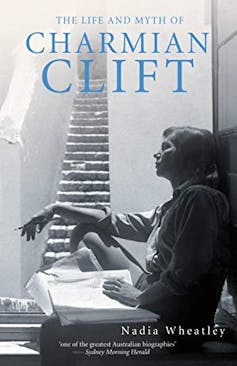

Wallis’s observations are accurate, and prophetic, in noting Clift’s capacity for self-mythologising and her belief that both she and her Hydra idyll would be remembered. Nearly four decades after Clift returned from Greece to Australia amid the acclaim for My Brother Jack, she did become the subject of an excellent biography, Nadia Wheatley’s The Life and Myth of Charmian Clift (2001).

But there were also failures amongst the success. The vision she and Johnston shared for a writing life on Hydra floundered amid poverty, alcoholism and illness. Their return to Australia in 1964 was an unlikely triumph for Johnston following the success of My Brother Jack, but Clift did not return with the same profile.

Wheatley also traced another of Clift’s great disappointments – her failure to complete her long-dreamt of autobiographical novel The End of the Morning, a struggle that was the subject of Susan Johnson’s 2004 novel, The Broken Book.

Clift did, however, leave an autobiography of sorts, in her newspaper articles. These often focused on domestic circumstances and everyday thoughts – ranging from conscription, to the rise of the Greek military junta after she left Hydra, to the changing social circumstances in Australia, and her daughter’s engagement.

These articles might not have always reflected the experiences of her readers – not everyone invited Sidney Nolan over for drinks – but Clift’s first-person narratives of a life lived with great passion and a sceptical eye to the consequences, garnered a large readership.

These readers responded to an incisive intellect with a vision of a culturally enriched Australia. She understood well the need for the country to outgrow its entrenched conservatism in order to realise its potential; and she emerged as a generous spirit who realised that the dreams and passions that drove her life were found everywhere in Australian suburbs.

Wallis’s detection of Clift’s hubris and narcissism paints her as a potentially tragic figure. It was a fate she perhaps fulfilled, when Johnston eventually wrote of Clift’s infidelities on Hydra. Clift took her own life on July 8 1969, an event that curtailed her voice while leaving behind a legacy of loyal and grieving readers.

A natural cosmopolitan

Clift’s is one of the voices – and one of the most important female voices – that rose above the crowd during the post-war period, as the western world unknowingly girded itself for the social revolution that was to come.

Through her columns she advocated for a bolder, more outward looking future, and as someone who was naturally cosmopolitan she was avidly interested in seeing Australia become more open to the world and better integrated into the Asia-Pacific.

She didn’t always get it right (an essay decrying the rise of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones stands out!), but she helped navigate the path to a more broad-minded and inclusive vision of Australia.

Over the years Clift has emerged as someone who was not only modern, but also engaged in that most post-modern of activities, self-creation. For while Wallis scorned Clift’s self-mythologising at the time, it might now be recognised as the finest gift of the creative artist – to re-make oneself in the image of a world yet to be made. It was her gift to her readers and Australia.