This week, the Australian Government announced that it would not send a minister to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations in Poland for the first time since 1997. This announcement came on the back of a cancelled stakeholder meeting on Wednesday, traditionally held in advance of UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (CoP) meetings.

It’s been a bad week for advocates of climate change action in Australia. Former Prime Minister John Howard, in a speech to a gathering of climate denialists in the UK, questioned the scientific consensus on climate change. His “instinct” was that claims of climate catastrophe were exaggerated.

He also suggested that an international agreement was beyond the current climate framework, and praised Abbott’s climate policy.

Meanwhile the government continued to pressure opposing forces in the senate to support the repeal of the carbon tax. Environment minister Greg Hunt was telling anyone who would listen that the repeal of the tax would immediately drive down electricity prices across the country.

Aside from the issue that the government cannot determine electricity pricing, it was hardly inspiring for climate activists to hear Australia’s environment minister championing the cause for cheap electricity.

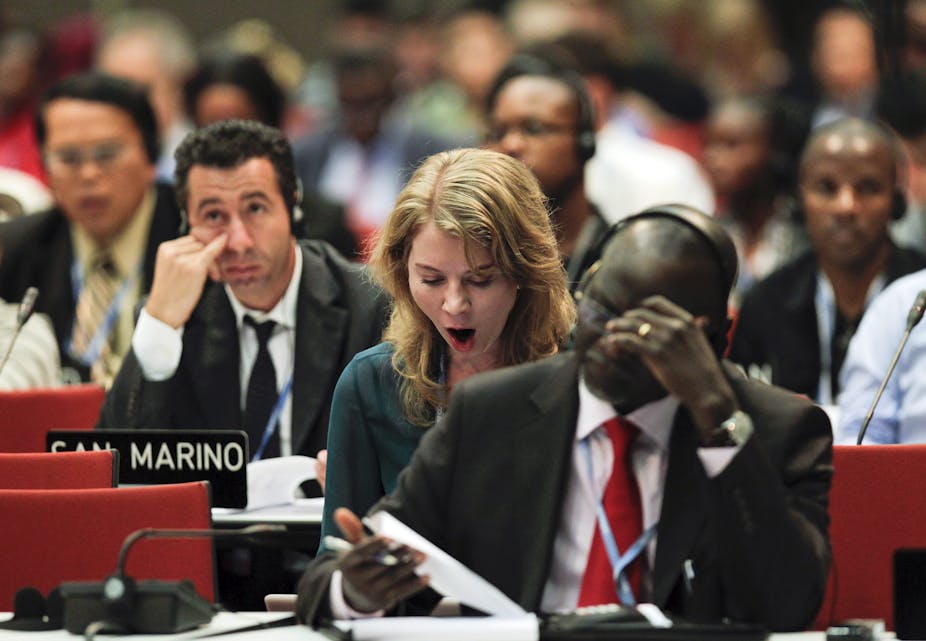

In that sense, the announcement that Australia’s chief representative in Warsaw would be the Climate Ambassador Justin Lee — rather than the Prime Minister, the foreign minister or the environment minister — is hardly surprising.

Yet as history shows, with the possible exception of the Howard era, Australia’s climate diplomacy has generally outpaced its domestic action on climate change.

Kevin Rudd personally attended two of the three climate meetings during his time as Prime Minister, acting as a “friend of the chair” at Copenhagen. He also took among the largest international delegations to these meetings. Yet in the face of political opposition and declining popular support, he famously dumped the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme and its centrepiece, the emissions trading scheme.

Bob Hawke ensured that Australia was among the leaders in promoting an international agreement. He also committed Australia to an interim planning target for greenhouse emissions reduction, well before other most other developed countries. Yet his government outlined few major policy initiatives beyond an investment in climate research.

Paul Keating promised that no domestic climate action would be undertaken if it had adverse economic effects. But he made it clear that Australia would not risk being isolated from an international agreement on climate change.

And even John Howard, who reduced funding for climate programs and by some accounts allowed a cabal of fossil fuel industry insiders unprecedented input into climate policy, continued to suggest that Australia would aim to meet Kyoto targets while pouring scorn on the treaty itself.

In that sense, the recent announcement suggests more of an alignment of domestic climate policy and climate diplomacy than has traditionally been the case. It also suggests that the suspicion of multilateralism, a hallmark of a conservative foreign policy agenda, is likely to continue in Australia’s foreign policy outlook.

But the climate conference snub is one with troubling implications for climate politics and Australian foreign policy generally. Post-election we’ve seen an assault on climate policy, and lingering suspicion over whether Abbott has genuinely put his denialist tendencies behind him. These negotiations provide an opportunity for the government to signal a commitment to action on climate change, both domestically and internationally.

Australia should be sending the message that it is an engaged and proactive member of the international community, concerned with helping to forge global solutions to global problems. The desire to be, and be seen to be, a “good international citizen” certainly shaped the Hawke and Keating Labor governments’ engagement with climate change diplomacy. And it allowed Australia to play a constructive role in the growing international efforts to act on climate change, even despite the limits of domestic climate policy.

There is a further, paradoxical dimension to Abbott’s UNFCCC snub. If climate change is viewed through the lens of the narrow and short-term national economic interest, the future of Australia’s coal exports actually hinges on the terms of international agreements on climate change. If the Abbott government is determined to prop up this industry for a little longer, the government needs strong representation to put this case to the international community as effectively as possible.

Either way, whether as a constructive member of the international community or a determined protector of Australia’s immediate economic interests, the Australian government needs to send strong representation to UNFCCC meetings. On the verge of 2015 talks that shape to be the most important since Kyoto in 1997, disengagement from the climate regime at this point sends entirely the wrong message, both domestically and internationally. And it suggests that the Coalition’s shaky foreign and climate policy start is set to continue.