On Sunday, the Australian Labor Party voted 206 to 185 in favour of changing one part of the party’s longstanding and non-negotiable platform on uranium exports: that recipient states must be members of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT).

The express intention of the change in policy platform is to lift the ban on uranium sales to India, who are among those three states globally that remain outside – and have no intention of joining – the NPT.

With the Coalition having been in support of such a move for some time, the vote is expected to have immediate policy ramifications.

Of little consequence now, the Greens do have a well-known policy position on uranium that clearly states: “The Australian Greens will […] prohibit the exploration for, and mining and export of, uranium”.

Misrepresenting India’s record

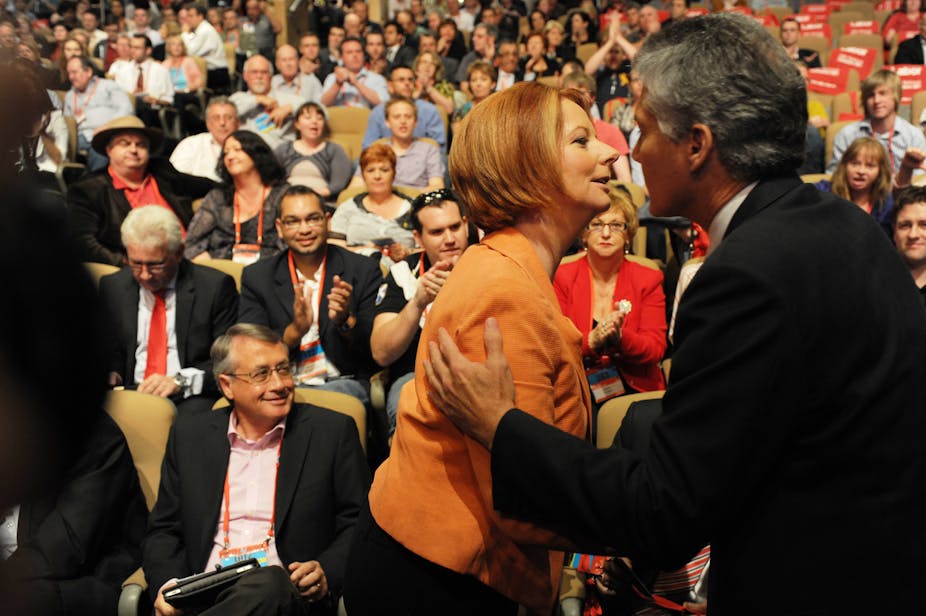

Quite apart from what I have elsewhere labelled the “moral syncretism” and undue domestic orientation of the perceived benefits initially provided by Prime Minister Julia Gillard – arguments irresponsibly taken further by lobbyists in the immediate days – it is a grave error to cite India’s nuclear weapons record – which is sub-optimal, not “exemplary”, as is often recycled – as evidence in support of a policy change that is predominately driven by political, commercial and diplomatic pressures.

Indeed, according to the Australia and Japan-led International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament report in 2009:

“10.5… One criticism – frequently voiced since the India agreement – is that [Nuclear Suppliers Group] members may be driven by commercial incentives to be less rigorous in their approach to countries not applying comprehensive safeguards or not party to the NPT.”

“10.7 The main substantive problem with the deal is that it removed all non-proliferation barriers to nuclear trade with India in return for very few significant non-proliferation and disarmament commitments by it. The view was taken that partial controls – with civilian facilities safeguarded – were better than none.”

Driven by dollars

Two years after these dire warnings – incidentally by an International Commission co-chaired by our former Foreign Minister Gareth Evans and instigated by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd – Gillard also appears to be primarily “driven by commercial incentives” and a perceived diplomatic dividend.

Indeed, proponents of the platform change generally made no acknowledgment that India were the first and only state in the world to acquire nuclear weapons as a result of international cooperation on the basis of it being for peaceful purposes – nor her belligerent testing in the mid-1990s; her rather public nuclear arms race with Pakistan; her failure to fully comply with international safeguards and monitoring initiatives; her problems with the US despite a comparable bilateral agreement in place concerning technology and expertise. Nor the rather significant point that none of the cited measures are enforceable under international law – they are considerably difficult to monitor, verify and enforce.

It is worth noting, that six years later, some prominent arms control experts in the United States are still lamenting the lack of international security and arms control benefits to have flowed from the US-India deal:

“[…] nonproliferation norms took a hit from the U.S.-India civil nuclear deal and, at best, will take time to reinforce. The deal has added to the IAEA’s woes and has made the NSG a weaker institution.”

And sadly for Gillard and those favouring uranium exports, among the five pitfalls and misnomers of the US-India deal has been that the:

“[…] the arc of U.S.-Indian relations has improved, but with far less loft than the Bush administration’s deal makers conceived”.

The power of lobbyists

There are numerous lessons to be learned from the US experience, particularly since the similarities in the way the matter was debated there.

There as in here, well-funded and resourced lobby groups successfully denied Australian’s of a debate, and a complacent and shameful standard of media proliferated falsehoods and empty rhetoric as if reasoned evidence such that even Foreign Minister Kevin Rudd – who as recently as last month strongly opposed any deal with India – begrudgingly toed the line of the party leader given the announcement was made whilst he was in Dehli.

For instance, following the vote, Nitin Pai, editor of Pragati – The Indian National Interest Review, and Fellow at The Takshashila Institution tweeted that:

@Rory_Medcalf And let me say that the consistent policy advocacy by a certain Sydney based think tank surely played an important role.

Expectedly, Rory tweeted back to the effect that Lowy staff have all reached independent views on the matter - but given the hive of activity from the Institute in favour of relaxed uranium controls, Pai’s assertion was a reasonable one to make.

Arms control considerations

For India has repeatedly and consistently stymied arms control and international security norms in recent times – including abstaining from both the UN Security Council decisions to take “all necessary measures” against Gaddafi’s Libya, and the IAEA’s recent efforts to sanction Syria for noncompliance.

And more importantly still, despite having now changed party platform, as yet Australia have made very few inroads that improve security outcomes in return for access to its uranium.

For instance, it remains unlikely India will sign the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) or cease production of fissile material for use in nuclear weapons. Similarly, whilst India remains outside the international Missile Technology Control Regime for instance, since 2005 it had voluntarily adhered to some of its guidelines, albeit without the same standards of verification. India has, at governmental level, openly suggested that it seeks to import uranium in order to free up domestic supplies for its nuclear program. One obvious downside to India’s supposed strict separation of its nuclear energy and weapon programs is that whilst some IAEA inspections are permitted at the former, none are carried out at the latter.

Contrary to the taunts of lobbyists, these are not just single-minded concerns held by those wishing to preserve out-dated or discriminatory arms control mechanisms. For instance, according to an academic out of Australian National University, a strict interpretation of Article 4 of the South Pacific Nuclear Weapons Free Zone – to which Australia is a signatory – would prohibit Australia from trading with India until and unless comprehensive or “full-scope” safeguards are routinely carried out on all of their nuclear research and production facilities.

In the words of then Foreign Minister Alexander Downer when that Treaty was signed in 1996:

“Article 4 (a) of the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty imposes a legal obligation not to provide nuclear material unless subject to the safeguards required by Article III.1 of the NPT; that is fullscope safeguards.”

So there is much for Gillard’s government to do before a deal can be done.

What is clear to me is that Australia’s prospects of being awarded a seat on the UN Security Council next year are bound to have suffered already.