Fifty years ago, on the morning of August 23, 1966, Vincent Lingiari led a walk-off of 200 Gurindji, Mudburra and Warlpiri workers and their families from a remote Northern Territory cattle station, escaping a century of servitude.

The families rejected the pleas of their British multinational employer Vestey’s to return to the Wave Hill station, re-occupied an area of their own land at Wattie Creek, and fought until the nation’s leaders heeded their cause. Nine years later, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam symbolically returned the Gurindji’s country with a handful of red dirt – a story many Australians know from the song From Little Things, Big Things Grow.

But how much did the 1966 Wave Hill Walk-Off, or the historic 1975 meeting between Whitlam and Lingiari, really improve life for the Gurindji people? And how significant was the walk-off in the fight for Indigenous recognition and land rights in Australia?

A Handful of Sand: The Gurindji Struggle, After the Walk-Off, published today, tells that story. This edited extract reveals the drama and accidental comedy of the day the prime minister and his entourage descended on the remote community of Daguragu (formerly Wattie Creek) for the “hand back” on August 16, 1975 – and its bittersweet aftermath.

Whitlam flew up in a BAC 1-11 [jet]. The airstrip… wasn’t quite long enough for it [laughs]. I remember that when he landed, there were all these dignitaries waiting out there for Gough, but he didn’t stop in time and went hurtling through the fence. It was a pretty spectacular start to the day’s events. – Geoff Eames, Central Land Council lawyer.

It was just after midday when Whitlam and his wife Margaret stepped onto Gurindji soil for the first time. According to a very young onlooker, the prime minister “stood there like a great big giant and [shook] each old people hand”. In her blue slacksuit, Mrs Whitlam also began mixing with the crowd, embracing local infants.

A succession of former ministers — all of whom had promised the Gurindji varying amounts of land — milled about. Meanwhile, a “tethered goat [ate] rubbish with great solemnity”.

After introductions and greetings, the day’s program began under the shade of a bough shed. Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Les Johnson optimistically reassured the audience that with the government’s forthcoming Land Rights Act, the Gurindji could convert their lease to proper land rights, making them legal owners “later in the year”. (In reality, that didn’t happen for more than a decade.)

The general manager of Vestey’s Angliss group Roger Golding announced that Lord Vestey would give the Gurindji a gift of 400 cattle. Golding wished the new Murramulla Gurindji Company every success – though he also made a jibe at the protesters who had stormed his company’s offices some years earlier. Lupngiari — a significant player in the Gurindji’s struggle — sat back, ignored by photographers, rolling a smoke.

On the prime ministerial jet that morning, public servant turned Aboriginal affairs adviser H.C. ‘Nugget’ Coombs urged Whitlam to keep his speech short and invest the day with a sense of ceremony.

Coombs recounted a story told by anthropologist Bill Stanner: how Wurundjeri elders had formalised their people’s 1835 land treaty with encroaching settlers at Port Phillip by placing soil into the hand of explorer John Batman. Hearing Coombs’ suggestion that the PM might reverse the gesture with Lingiari, Whitlam revised his performance plan for Daguragu on the spot.

When it came to his turn to speak, Whitlam congratulated the Gurindji and their supporters on their victory after a nine-year “fight for justice”. Promising that the Australian government would “help you in your plans to use this land fruitfully”, his speech concluded with the words:

Vincent Lingiari, I solemnly hand to you these deeds as proof, in Australian law, that these lands belong to the Gurindji people, and I put into your hands this piece of the earth itself as a sign that we restore them to you and your children forever.

In finishing, Whitlam handed Lingiari the new deeds to the Gurindji’s land, now officially dubbed NT Pastoral Lease 805. Then, to the joy of assembled photographers, he stooped down, grabbed a handful of red earth, and poured it into Lingiari’s open palm.

Vestey pastoral inspector Cec Watts and his wife Dawn remember how Lingiari — knowing the symbolic importance of the soil he had been given — then quietly tried dispose of the red dirt without offending the assembled kartiya (white people). As the couple recalled:

Cec: I was standing quite close to Vincent, and Gough gave him this handful of dirt, symbolically, and the old bloke sort of let it drift out of his hand.

Dawn: He didn’t know what to do with it.

Cec: Poor old bugger… He put it behind his back.

Dawn: They could have given him a little box.

Lingiari — who according to one reporter was struck with a case of nerves — responded to Whitlam and the crowd in his own language:

The important white men are giving us this land ceremonially… It belonged to the whites, but today it is in the hands of us Aboriginals all around here. Let us live happily as mates, let us not make it hard for each other… They will give us cattle, they will give us horses, and we will be happy… These important white men have come here to our ceremonial ground and they are welcome…

You (Gurindji) must keep this land safe for yourselves, it does not belong to any different Welfare man. They took our country away from us, now they have bought it back ceremonially.

After Whitlam gave the old man even more dirt for the benefit of the press, photographer Mervyn Bishop’s images of the “handover” became some of the most recognised in Australian political history. The power of the photos rested in the symbolism of Whitlam’s gesture, made on behalf of millions concerned by Aboriginal dispossession.

The handover implicitly acknowledged the moral rightfuness of the Gurindji’s stand, and the historical injustices done to them by the Europeans on their country. It was by dint of the Gurindji’s hard slog at Wattie Creek that they had successfully brought all this to the nation’s attention. The handover day was the old Gurindji men’s finest hour, and their victory.

Lingiari made his speech, and a party followed. Chops, sausages and fruit were served before painted-up members of the track mob and others danced. Mindful of the whites’ need to mark every occasion by consuming liquor, Daguragu’s elders had waived their alcohol ban for the day, but precious little was on hand.

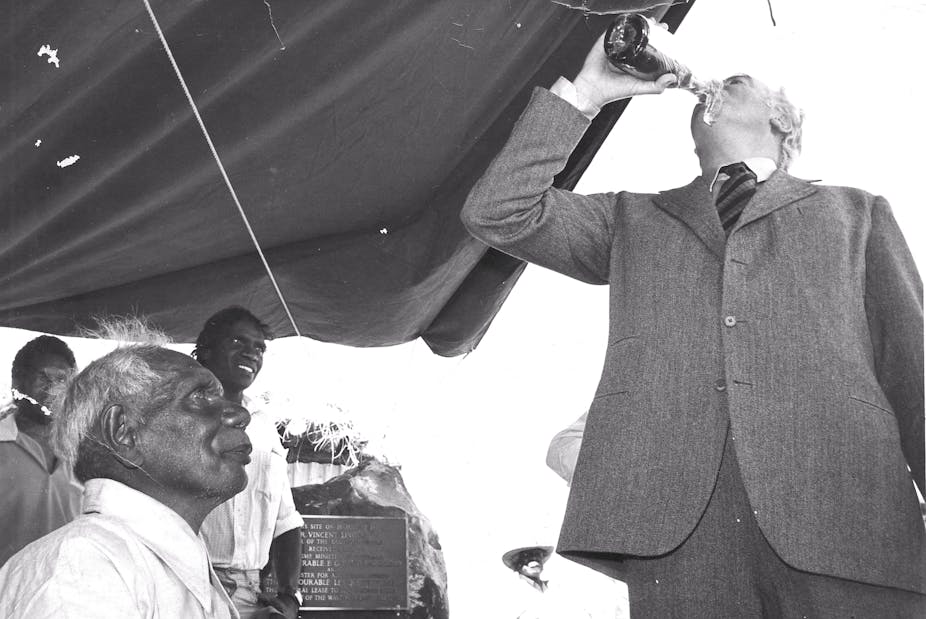

Guests quickly learned that the line “One for Mrs Whitlam, please” would guarantee them a cold beer. The prime minister “poured champagne down his copious gullet” from the bottle, according to agronomist Rob Wesley-Smith, before passing it to a startled Lingiari. The old man had sworn off drinking the year before, but he took a swig — and requested Whitlam’s help to prevent the ill-effects grog was having on his community.

Amongst such excitement, the Gurindji leader gave the new title deeds to his lawyer, Geoff Eames, for safekeeping. With enthusiastic residents wanting to examine the documents, Eames lost them in the crowd. At that point he was approached by Whitlam, announcing there had been requests for photographs of the black and white statesmen holding the parchment. When Eames replied meekly that he didn’t know where it was, Whitlam’s response was quintessential:

What? It took them 200 years to get their land back, and you’ve lost it in ten minutes?

Eventually the deed was located, “all stained with red dirt, it had been passed through so many hands”.

After the bonhomie subsided and the VIPs departed for the Wave Hill airstrip, Daguragu’s elders were apparently “disgusted” by the empty beer cans left behind.

In rural Queensland the day after the ceremony, Whitlam claimed on radio that “for the first time, Aboriginal people have been given rights to their own land”.

The PM was gilding the lily, for although he was clear that the government’s transferral of a pastoral lease to the Gurindji was just the first step towards returning their land in perpetuity, the “rights” he’d conferred were merely those enjoyed by Vestey’s and other NT pastoralists. Contrary to Whitlam’s spin, the reality was that other Aboriginal groups had pipped the Gurindji to the post on that count, too.

The 1966 Wave Hill Walk-Off and the tireless years of campaigning that followed were nationally significant, not least because they helped inspire the Whitlam government’s 1973–74 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Land Rights. Its findings were used to draft the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 – the most far-reaching land rights laws in any part of Australia.

But as for their own land rights, it would take the Gurindji people another 11 years before they could finally call their land their own.

* A Handful of Sand: The Gurindji Struggle, After the Walk-Off is published by Monash University Publishing.