Mary of Egypt, a fourth-century saint with a large medieval following, had a thriving and active sex life. But we only find out about Mary’s past from her repudiation of it.

She lived in poverty, earning a living by begging and spinning flax. For over 17 years, she enjoyed erotic liaisons with as many men as she liked: according to her male biographer, Sophronios, her life was all about libidinous pleasure.

Sophronios takes over her voice in an outpouring of shame. In his account, Mary says she is “ashamed even to think about how I corrupted my virginity” and reflects on “how recklessly and immodestly I lived with my passion for sexual intercourse”.

She admits to having had “an insatiable and unrestrained desire for passionate love”. She “was drawn to wallow in filth”.

Even today, Mary’s salacious past is understood by the church as reprehensible, something to atone for and repent over.

Why should we talk about Mary of Egypt today? I was drawn to her multifaceted identity as a woman desert saint, an ascetic, a highly sexual individual navigating her own redemption. Is there something edifying about Mary’s story – or does it go into the feminist shame file?

Read more: 'A promiscuous she-pope with a dilated cervix': the legend of Pope Joan, who gave birth on a horse

The antithesis of seductress

Mary’s rejection of her previous life came when she was unable to enter a church.

One day, she encountered a group of young sailors bound for a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to venerate the Holy Cross. She went along for the ride, seducing the young men entirely for the fun and excitement of it.

Upon attempting to enter the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, an invisible barrier prevented her from crossing the threshold. In that moment she experienced an epiphany. Her life of pleasure was redefined as a life of sin. She looked up and saw an icon of the Virgin Mary above her. She vowed to forsake all her worldly desires and follow wherever the Virgin would guide her.

In Sophronios’ biography, Mary then embraced the life of solitude and asceticism in the desert that would make her famous – and a saint.

Physically and psychologically, she became the antithesis of seductress. She endured harsh conditions without clothing, becoming sunburnt and only eating meagre portions of bread for over 40 years.

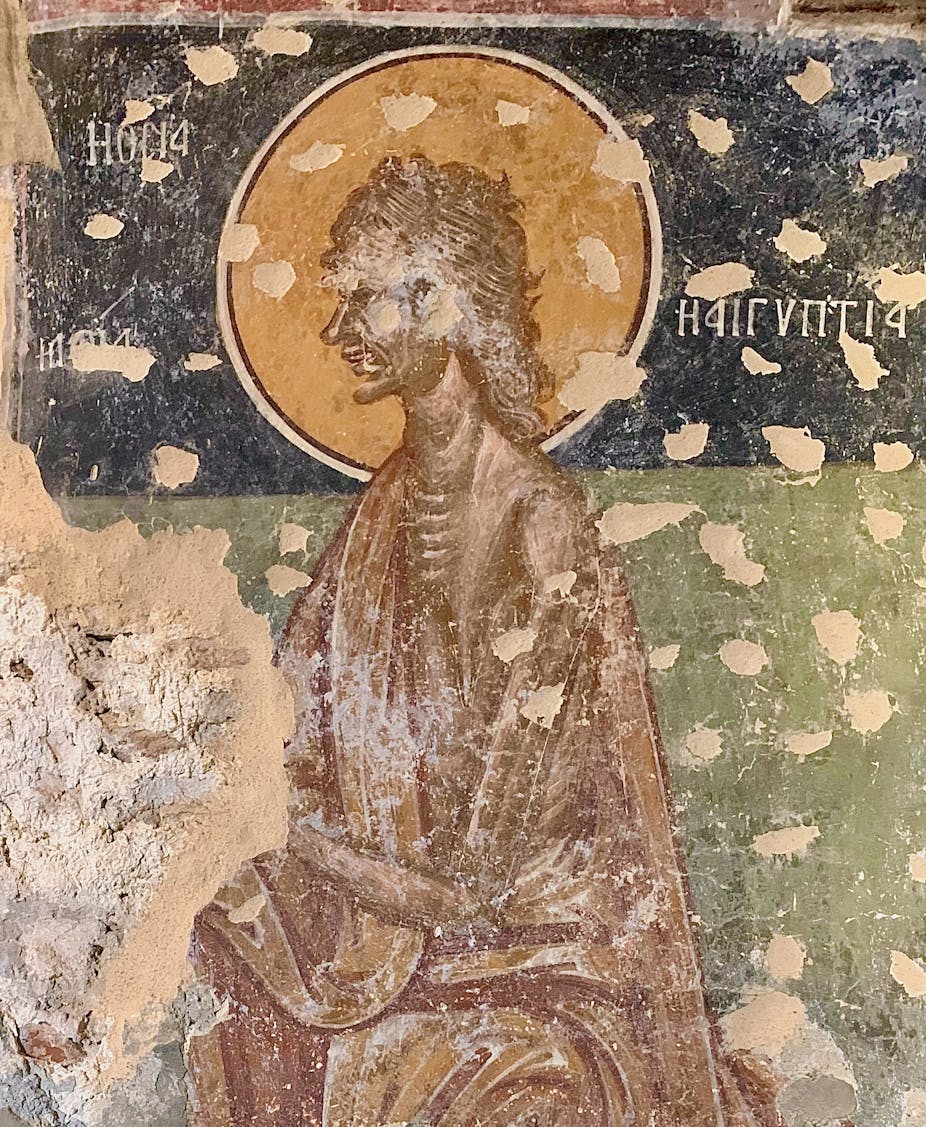

In Byzantine frescoes, Mary is depicted as old and gaunt, emaciated and with unkempt grey hair. You’ll never see Mary enjoying her own beauty and sexuality as a young woman; rather, she embodies virtue as a wraith who forswears her former happiness.

When she was canonised as a saint, it was because she fulfilled the Christian ideal of repentance to an extreme degree.

Over the centuries, Mary’s narrative has been preserved and shared through various mediums, including literature, art and at least one hammed-up film.

Repentance and redemption

Sophronius indicates her promiscuity had a corrupting influence on men. But her past is understood as reprehensible within Mary herself: the relish she obtained from sexual pleasure is described as wantonness (ἀσελγεία) and debauchery (πορνεία).

Because these qualities are within you and your joy, they are the opposite of devotion and sacrifice expected by God. They therefore must be spurned.

But with the focus on repentance and redemption in Mary’s story, two strange qualities emerge.

First, Mary’s repentance is proportional to her suffering in the desert. The more abject her physical condition, the greater her new devotion.

Second – and this is the lurid paradox – Mary’s repentance is proportional to the extent of her previous lust. The lustier she was, the greater is her holiness now, because she has rejected it.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, contrition is especially meaningful when someone has done something especially wayward in the past. To understand the holiness of our repentant saint, we have to have a live picture of their previous transgressions.

This tells us a lot about society. For a woman, the saint can never altogether transcend her past. It stays with her, haunting her right down to the symbolic nakedness: once a vehicle for her pleasure; now a monument to her shame.

Read more: Madonna or whore; frigid or a slut: why women are still bearing the brunt of sexual slurs

Purity and piety

Since the sixth century, Mary’s story has served as a means of control over women’s behaviour and sexuality.

Shame over erotic behaviour is not unique to Mary. Other women saints, such as Pelagia of Antioch, who was a reformed harlot, and St Thaïs of Egypt, who underwent a profound conversion, similarly had their narratives framed in terms of wrongfulness atoned for.

Thanks to contemporary feminist discourse, we can start to approach Mary’s story through a new lens: is the way we talk about Mary simply a form of slut-shaming?

Mary’s story reflects the belief a woman’s worth and virtue were intrinsically tied to an ideal of sexual purity. It reinforces long-held expectations of women as chaste, obedient and pious individuals. Women were either seen as temptresses, associated with sin and debauchery, or as virtuous saints, embodying purity and piety.

Paradoxically, to go from one to the other can make you a saint.

Mary’s story no longer holds the sway in the church it once did. The desert saints have not travelled well because it is harder to see what they should be ashamed of.

Yet it is possible to find Mary’s story touching in its own terms: the pathetic frail figure of the saint in Byzantine art captures the pathos of a person wrestling with the burden of piety.

Read more: Standards for sainthood: what defines a 'miracle'?