The National Gallery of Victoria’s (NGV) International’s summer blockbuster Andy Warhol – Ai Weiwei packs a double whammy, with both an immediate wow factor and a lasting impact, that will leave you pondering new insights for days. The exhibition is curated to create a dialogue between the two artists, and this conversation operates on multiple levels on a variety of themes, and across time and space.

The show, developed with The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh (it will travel there in June 2016) and with the participation of Ai Weiwei, presents more than 300 works from the two artists and includes major new commissions, such as Letgo Room (2015): a room-scale installation featuring portraits of and quotes from Australian advocates for human rights and freedom of speech and information, constructed from knock-off Lego.

Works span a broad spectrum of media including paintings, screen prints, sculpture, film and video, photography, publishing and social media.

Warhol, the iconic figure of 20th-century modernity, the epitome of American capitalist culture and the cult of celebrity, represents the last century, “the American century”.

Ai, conceptual artist and iconoclast, product of and rebel against Chinese communist culture, is the iconic artist/ activist of the 21st century, a century that Nobel Prize winner Joseph E. Stiglitz dubbed “the Chinese century”.

Although Ai never actually met Warhol, he was living in New York in the 1980s where Warhol was one of the focal points for the contemporary art scene, and the first book he bought in the English language on his arrival in America was The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (from A to B and Back Again) (1975).

Both artists were strongly influenced by Marcel Duchamp, who makes an appearance in the exhibition in Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests (1966) and as a profile crafted from a wire coathanger in Ai’s Hanging Man (2009).

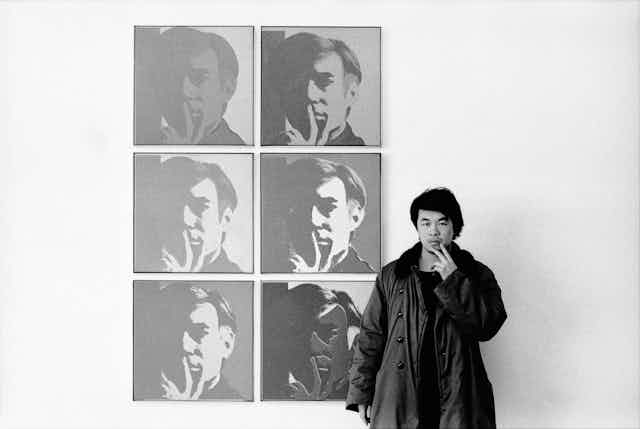

A self-portrait taken at the Museum of Modern Art in 1987 shows Ai assuming a Warholian pose in front of Warhol’s multiple Self-Portrait of 1966 (see main article image).

Warhol’s was an almost ubiquitous presence in the age of mass media on both the New York art scene and among the American celebrity set, exhaustively documented in Polaroids, candid shots, on film, on his television show, and through what Warhol referred to as his “wife”, his beloved Norelco tape recorder.

He can be seen as a forerunner to Ai’s saturation of social media. Ai blogged extensively, until the Chinese government shut him down in 2009, and currently uses video and Instagram and Twitter to document his own experiences, to draw attention to repression and injustice, and to advocate for freedom of expression.

Both men are characterised by large lives, and an artistic practice that spans multiple media and in which their own lived experience becomes part of their body of work.

Warhol’s studio became known as The Silver Factory and he aimed to make art that could be created by anyone, although was frequently involved in the processes of production himself:

The reason I’m painting this way is that I want to be a machine (1963).

Ai’s factory in Beijing, called FAKE Design, which in Chinese characters can be translated as “class development”, is in fact a real factory in which Ai, despite excellent draughtsmanship and artisanal skills, delegates the labour of production to a host of appropriately skilled workers:

I wanted to do some art works where I would not put any effort or skill into it (2003).

Despite Warhol’s somewhat disingenuous claim to be emptying the subject matter of his art of all meaning, there is implicit social criticism in much of his work, such as in the Death and Disaster series which includes his well-known screen prints of the electric chair (1967), and in which he examines the spectacle of death in American mass media culture.

Ai’s overt political activism can be both shocking and wholly engrossing. He has witnessed the dead with powerful works such as Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation 2008-2011 and 4851 (2009), in which he lists the names of the more than 5,000 children who died due to shoddy school construction during the Sichuan earthquake of 2008, and Straight (2012), in which a team of workers painstakingly use manual labour to straighten thousands of twisted rebars from the schools hit by the quake.

Other works, such as One Recluse (2010), the video in which the trial and death sentence of Yang Jia is investigated to reveal the questionable nature of independent justice in China’s state-controlled judicial system, are sobering statements of political protest.

But there is also much at the NGV that is highly entertaining. Ai’s interpretation of the Gangnam Style phenomenon, Caonima Style (2012), both protests censorship in China and makes one smile.

His raincoat with a condom attached at waist height, Safe Sex (1986), draws attention to the culture of fear surrounding the AIDS epidemic, while also conjuring up the classic image of the flasher in the park, naked under his raincoat.

Warhol’s Polaroids and screen tests induce even the most hardened cynic to indulge in some vicarious celebrity spotting. Both Warhol’s Silver Cloud Pillows helium balloon installation (1966), and Ai’s 21st-century interpretation, Bird Balloon (2015), which features golden alpacas and red Twitter birds, provide good interactive fun.

Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable gallery, with pounding music, live performance footage and stills projected onto all four walls, is an immersive experience which can be enjoyed supine from a beanbag on the floor and serves to remind one of just how ahead of his time Warhol was.

Whether or not you are accompanied by a child who provides a convenient excuse, do not miss the Studio Cats section of the exhibition (free entry) which is primarily targeted at children.

It is a joyous interactive space in which everything feline is celebrated – Andy Warhol had 25 studio cats, Ai Weiwei has about 30 – and in which children can create their own clever image captions and videos using a multimedia platform and build sculptures from Warhol’s iconic Brillo Soap Pads and Heinz Ketchup boxes.

This huge exhibition spans most of the ground floor of the gallery and is best encountered on a day in which you have plenty of time to browse.

Andy Warhol – Ai Weiwei is at the NGV International, Melbourne, until April 24, 2016. Details here.