The resounding victory of Alberto Fernández and former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s alliance in Argentina’s primary elections came as a shock to many. They comfortably won in 22 of the 24 jurisdictions in the initial vote that decides which parties can stand in the general election later in the year and is seen as a precursor of final vote in October.

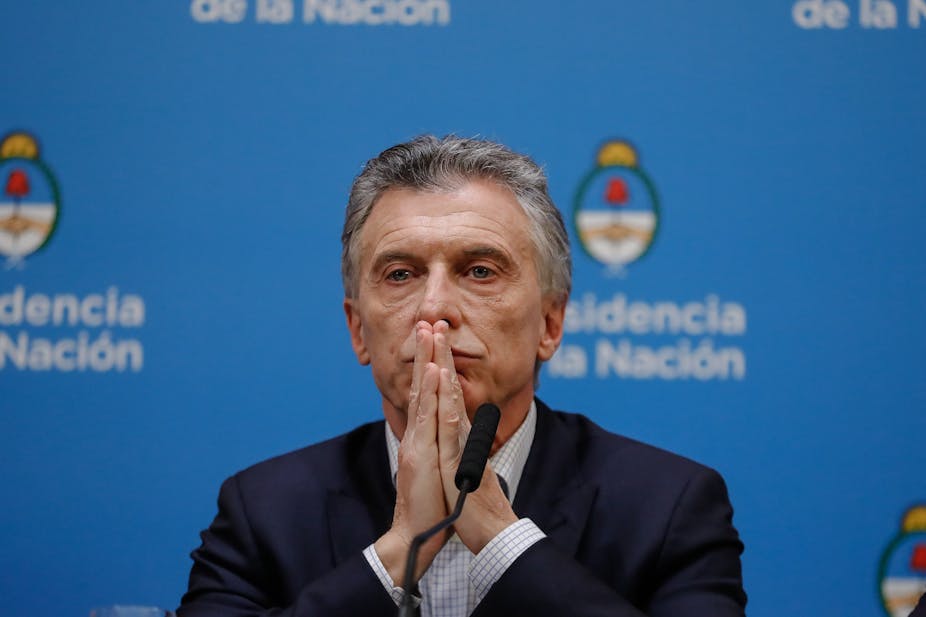

The incumbent, pro-market president, Mauricio Macri received just 32% of the total vote share while Fernández got 47.6%. It marks a clear defeat for Macri’s Juntos por el Cambio or “Together for Change” government coalition and its neoliberal political project. And it was a triumph for the Peronist bloc, which managed to bring together the left-wing elements associated with Kirchner and her husband’s previous governments, with more moderate centre-right sections of the same political movement.

Read more: Alberto Fernández – who is the frontrunner for Argentina's presidency?

Financial markets reacted rapidly to the result. Argentina’s stock markets and currency plunged, with the peso falling about 28% against the US dollar. The alarming reaction from Wall Street led to queues in Argentina for basics like petrol and food before the currency devaluation was transferred to prices.

Not only did the government seemingly lose its chances of continuing beyond 2019. In just a week, the economy minister was fired, the country’s reserves dropped by almost US$4 billion and Argentina’s debt was rated almost as a default liability by ratings agencies and global markets.

Economic woes

Argentina is no stranger to economic crisis. But understanding Argentina’s economic situation goes a long way toward explaining the turn against Macri’s government in the recent polls.

For ordinary people, inflation has risen from 22% to 48% since December 2015 and the currency fell from 13 pesos to the US dollar to 45 pesos to the dollar before the primary elections. It then fell further to 58-62 pesos after the results. Available data shows that from October 2015 to October 2018 electricity prices rose between 1,053% and 2,388%; gas for households rose between 462% and 1,353%; and water prices were up by 832% for houses with metres, and 554% for those without metres.

Three and a half years of austerity policies, budget cuts and an end to subsidies of everyday necessities like water and electricity has made life difficult for the majority of Argentinian households. Research shows that 33% of the country lives in poverty, and this is rising, with about 4m more people living in poverty in 2019 than a year ago.

Meanwhile the country’s debt levels are unsustainable. As underlined by the social scientist Daniel Ozarow, Argentina’s enormous debt is a major source of instability. And Macri’s government exacerbated the country’s debt troubles with reforms that leave the country at the mercy of financial speculators. This deregulation allows foreign investors to pull out their money with no restrictions, helping fuel the recent currency crash.

Macri also took out another US$56.3 billion loan from the IMF “to help the country’s financing needs” in 2018. An estimated 75% of the population opposed the deal, which requires Argentina to run a balanced budget by 2019 and cut its external deficit. As well as more cuts, the IMF deal fostered feelings of economic subservience to foreign powers. Many Argentinians have vivid memories of the economic disaster that followed IMF policies there in the 1990s.

Longstanding issues

But the many problems with Argentina’s economy cannot all be put down to Macri’s policies. They are the result of long-term issues related to the country’s economic model. As sociologist Adrián Piva has written, Argentina has some fundamental issues that predate the Macri government and were a feature of the previous Kirchner administrations, too.

Many of these issues were masked by a commodity boom which lasted from 2002-2012. This brought in big revenues and helped the Kirchners put Argentina’s deep depression of 1998-2002 behind them. But the end of the commodity boom in 2013 revealed the problems with depending on this industry, which did not create a large number of jobs and mostly benefited the country’s landowning elites.

More fundamentally, Argentina is a country on the periphery of the global economy that, like many developing countries, has struggled to slot into a global system whose rules are not written in its favour. Weak investment, high inflation and currency outflows are all longstanding issues.

Macri’s new coalition promised to solve these and reach “poverty zero” when elected in 2015, but those where campaign slogans he did nothing to accomplish. The CEO’s government, as it was called, planned to overhaul the economy with pro-market reforms but its small majority in government and the lack of social support for drastic changes limited his plans.

In fact, much got worse as a result of Macri’s market-driven approach. Plus, the substantial cuts to government spending and shrinking of the public sector meant people really felt the economy contract.

But, while the primary results show clear resistance to Macri’s way of managing the economy, what is likely to be the next government will still have fundamental issues to tackle. It should take heed of the unrest during Macri’s time in office, which was rooted in the idea that the costs of the country’s crisis should not be paid for by ordinary people.