Going from raw data the Australia-China trade relationship should be a source of celebration and congratulation. In 2013, bilateral trade came to A$140 billion, up 20% on the year before. Even better, unlike most other developed economies, the balance of trade was in Australia’s favour – two-thirds was exports, one-third imports.

There was an imbalance in the inward and outward investment figures too, though less dramatic, with Australia having slightly less than A$30 billion newly deployed in China, and China slightly more than the A$30 billion back in Australia.

But underneath the healthy statistics for trade and development are two nagging issues, the link between them being sustainability. The first concerns the composition of exports to China.

Of the A$94 billion in 2013, more than half were in resources. The Chinese addiction to using stuff dug from the ground in Australia to fuel its own growth has decreased as China’s growth rate has slowed a little, but still remains strong. When we come to services, however, the numbers reduce dramatically. In 2013, Australia exported A$6 billion of services to China.

Radical change

As the nature of the structure of the Chinese economy changes however, these figures will need to radically change. The services figure needs to rise, and the resources figure, stabilise. In fact, it is likely to fall.

We know something about what Chinese leaders want the structure of the Chinese economy to look like in the future from what current premier and macroeconomist-in-chief Li Keqiang has said in the past few years. According to him, China needs to raise domestic consumption, deepen its urbanisation from 50% to perhaps 70% of the population by 2020, reduce capital investment in fixed assets, and (the objective of critical interest to Australia) raise its services from 40% contribution to GDP growth at the moment to closer to 50% or 55%.

In late 2013, the Plenum document issued from the central government explicitly referred to this when it talked of the need to create an indigenous national finance system. It is into this market of urban living, service sector-using, higher-consuming Chinese that Australian companies have to find ways to sell their services and goods.

This market will need to grow as the avalanche of resources sold to China starts to dry up. The bottom line is that reliance on such high levels of resource sales at the moment is unsustainable. The structure of Australian trade to China has to change, and the services and finance strengths of Australia need to be used to address this.

A more diverse relationship

And this comes to the second issue. Reliance on bilateral trade alone will not be enough, and Australia will need to envisage a more diverse economic relationship. Foreign direct investment matters here, and the likelihood is that much more Chinese money will need to come here.

It will need to be outside the current favoured areas of state-owned enterprises in resources and private Chinese money into real estate. Over the last few years, Chinese investment has changed slightly from being 95% from the state companies to 85% in 2012-13. But non-state companies are likely to become more active in the external investment story.

This is important not just because of their potential as a source of job creating capital, but also because strategically they can serve as potential partners for Australian companies trying to find ways to get into the domestic market referred to above with its potential for demand and growth. We know that China is not an easy market to break into.

A free trade agreement

Smart Australian companies in sectors as diverse as agribusiness and hi-tech manufacturing, or services, may well consider selling equity to a Chinese partner to have someone to help them get access to the Chinese market. Conceptualising an intimate link between our two economies is unorthodox, but in the era of high globalisation, surely this sort of framework helps.

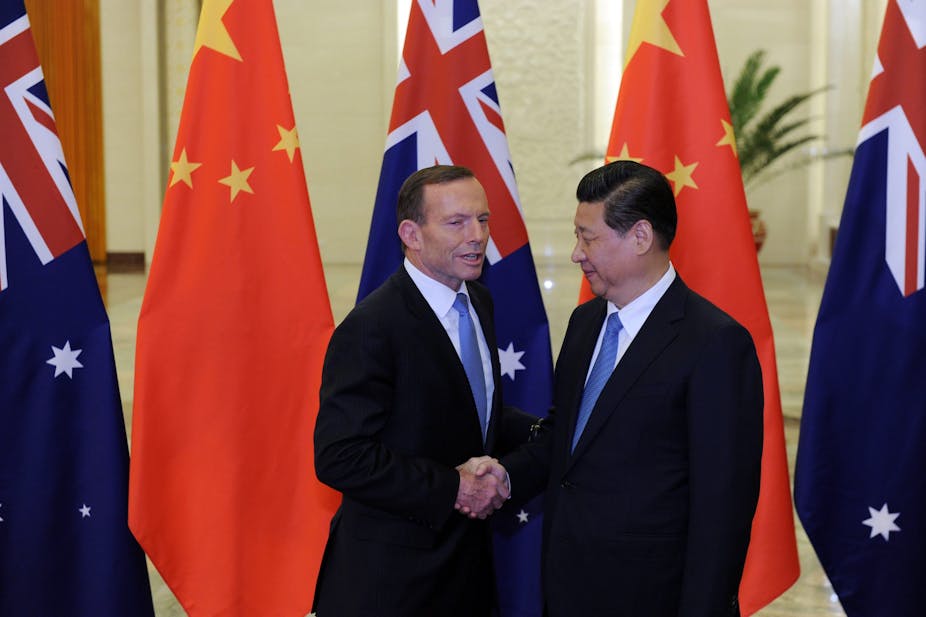

Over both these issues hangs the matter of a bilateral Free Trade Agreement. An FTA is of more political than economic use, but without the political framework nothing else can happen. The FTA negotiations offer a moment for China and Australia to forge a consensus on how much they have a shared understanding of these two challenges of sustainability and how to address them.

An FTA which lays the foundations for higher service and trade provision between China and Australia, and a more diverse investment relationship will be tough, but is a fight worth engaging in.

As we all know, however, once an FTA is in place it is up to companies to use their wits to secure better market access and go for sources of growth in each other’s economies that are more sustainable and offer a long-term future.

Professor Brown will be a panellist at the 2014 Economic and Social Outlook conference, hosted by the Melbourne Institute, on Thursday, July 3. He is the author of The New Emperors: Power and the Princelings in China, which has just been published.