At first glance the announcement by video entertainment and pay-television company Multichoice that it will be dropping controversial news channel ANN7 from its offering may be seen as another new “green shoot” in the “Cyril spring” following Cyril Ramaphosa’s election to head the governing African National Congress.

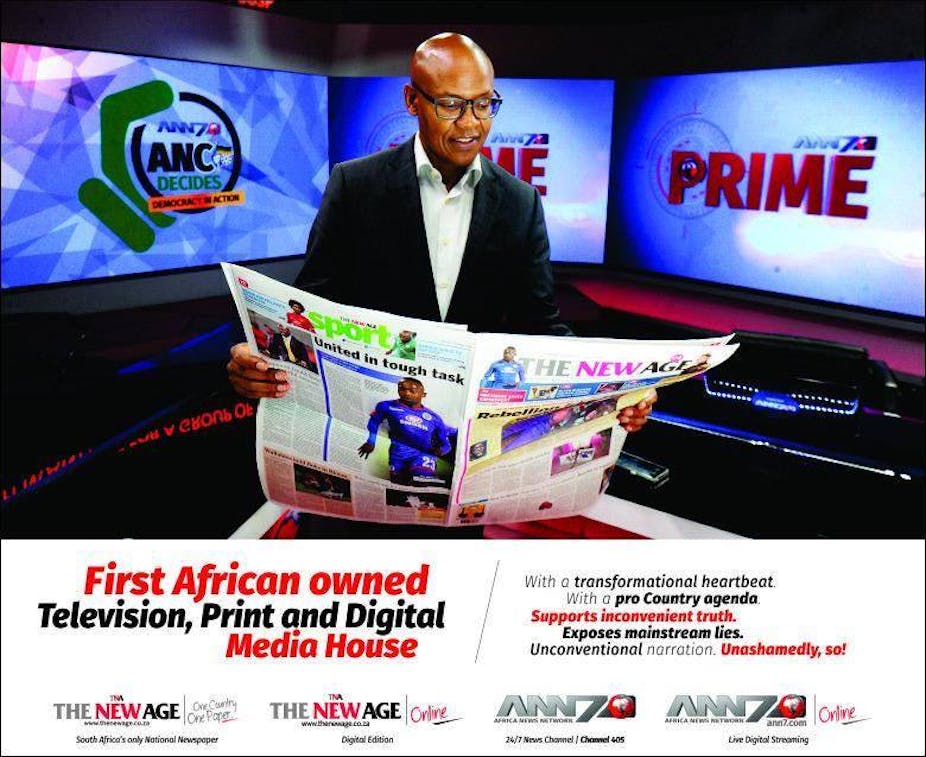

ANN7 is funded by the Gupta family who are close to the country’s President Jacob Zuma and are accused of having undue influence over him, including dictating cabinet appointments. As newly elected president of the ANC, Ramaphosa will take over running the country when Zuma goes. He is currently also the deputy president of the country.

But there’s more to Multichoice’s decision than a change in the political landscape. The company is also in the middle of managing a reputational crisis. The announcement to drop ANN7 was made on the same day that a report was released after an investigation into the company’s links with the Gupta family.

The probe looked at allegations that Multichoice had paid ANN7 exorbitant fees in return for airing a news channel on its satellite platform and allegations that Multichoice may have paid the broadcaster for political influence. The report found no evidence of wrongdoing. Nevertheless Multichoice cut its ties with ANN7.

There is no doubt that ANN7’s journalism is shoddy, biased and poor to the point of ridicule. It won’t be missed by anyone who values balanced or honest, truthful journalism. Its pro-Zuma stance often led to skewed reporting under the guise of transformation.

From a reputational management or branding perspective, Multichoice’s decision to drop ANN7 from its bouquet was probably the clever thing to do. But it does raise questions about media freedom, political pluralism and democratic debate. Perhaps more importantly, it prompts reflection on Multichoice’s concentration of power over the public sphere. These questions suggest that dropping ANN7 may send a bad signal for media freedom and democratic debate in South Africa.

Freedom of expression

The South African National Editor’s Forum has decried the decision. Their concern is informed by idea that the free exchange in the marketplace of ideas is healthy for democracy.

Political economists might offer a different critique. They would point to the tendency of the power of commercial media to be concentrated in the hands of a few, and to align itself with political power.

From both these perspectives, the Multichoice decision would raise questions about media freedom. The first perspective would suggest that there should be many different voices in a democratic public sphere, including disagreeable ones. The second would question the dominance of one player in a democratic media landscape, which alone has the power to decide what gets heard.

In a media sphere where, aided by social media, we are increasingly able to withdraw into our own echo chambers and “filter bubbles”, it is probably a better idea to listen to as wide a spectrum of political opinions and refute them with sound arguments. Closing them down and driving them underground, or into the hands of Twitterbots, is less strategic than just allowing the public to refute them on social media or vote with their remotes.

Then there is the question of consistency. Multichoice’s decision to drop ANN7 puts the broadcaster in a moral quandary. Audiences may laud what they see as a principled decision to push back at a news channel that defies ethical values such as balance, truthfulness and fairness. But they may then rightly assume that Multichoice approves of the content on all the other channels that it continues to carry.

What about the Chinese state-sponsored channel China Central Television (CCTV), recently rebranded as CGTN? Does it not also present slanted news? And what about Russia Today, also carried on the DStv network? Once a provider starts making editorial judgement calls, where does it stop?

Concentration and conglomeration

Media freedom does not only mean the absence of restrictions (sometimes referred to as a negative freedom, but also the presence of conditions that allow for the realisation of democratic ideals and purposes (positive freedom). In other words, it is not enough that South Africa’s Constitution guarantees freedom of expression if there are not enough opportunities available to express that freedom. The fact that a single platform has the power to decide what gets said in the public sphere is therefore a problem.

South Africa has one of the most concentrated media markets in the world, dominated by only four companies (Naspers, Independent, Tiso Blackstar and Caxton). This concentration is not conducive to democratic debate.

For a young democracy, a wide variety of voices is vitally important. It’s true that ANN7 didn’t contribute anything of worth to this plurality. But it’s equally true that commercial companies such as Multichoice should not hold disproportionate power over the public sphere.

This would matter less if the country’s public broadcaster did its job. A functioning, transparent public broadcaster is an important counterbalance in a hyper-commercialised broadcasting environment. Especially in a highly unequal country where access to commercial media is reserved for the minority that can pay for it. The country needs not only to see and hear a variety of political points of view, but also a diversity of lived experiences.

South Africans have not been not well-served by the public broadcaster in recent years. But there are signs that the new board might be turning the corner. The appointment of a new COO for the South African Broadcasting Corporation heralds a new management regime. The ongoing editorial policy review process is also a good sign. After all, if the media claims to play a role in democratic debate, listening to the public - rather than to politicians and their cronies - is a good place to start.