When people hear the word “Jonestown,” they usually think of horror and death.

Located in the South American country of Guyana, the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project was supposed to be the religious group’s “promised land.” In 1977 almost 1,000 Americans had moved to Jonestown, as it was called, hoping to create a new life.

Instead, tragedy struck. When U.S. Rep. Leo J. Ryan of California and three journalists attempted to leave after a visit to the community, a group of Jonestown residents assassinated them, fearing that negative reports would destroy their communal project.

A collective murder-suicide followed, a ritual that had been rehearsed on several occasions.

This time it was no rehearsal. On Nov. 18, 1978, more than 900 men, women and children died, including my two sisters, Carolyn Layton and Annie Moore, and my nephew, Kimo Prokes.

Photojournalist David Hume Kennerly’s aerial photograph of a landscape of brightly clothed lifeless bodies captures the magnitude of the disaster of that day.

In the more than 40 years since the tragedy, most stories, books, films and scholarship have tended to focus on the leader of Peoples Temple, Jim Jones, and the community that his followers attempted to carve out of the dense jungles of northwest Guyana. They might highlight the dangers of cults or the hazards of blind obedience.

But by fixating on the tragedy – and on the Jones of Jonestown – we miss the larger story of the Temple. We lose sight of a significant social movement that mobilized thousands of activists to change the world in ways small and large, from offering legal services to people too poor to afford a lawyer, to campaigning against apartheid.

It is a disservice to the lives, labors and aspirations of those who died to simply focus on their deaths.

I know that what happened on Nov. 18, 1978 doesn’t tell the complete story of my own family’s involvement – neither what happened in the years leading up to that dreadful day, nor the four decades that followed.

The impulse to learn the whole story prompted my husband, Fielding McGehee, and me to create the website Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple in 1998 – a large digital archive documenting the movement primarily in its own words through documents, reports and audiotapes. This, in turn, led the Special Collections Department at San Diego State University to develop the Peoples Temple Collection.

The problems with Jonestown are self-evident.

But that single event shouldn’t define the movement.

The Temple began as a church in the Pentecostal-Holiness tradition in Indianapolis in the 1950s.

In a deeply segregated city, it was one of the few places where black and white working-class congregants sat together in church on a Sunday morning. Its members provided various kinds of assistance to the poor – food, clothing, housing, legal advice – and the church and its pastor, Jim Jones, gained a reputation for fostering racial integration.

Investigative journalist Jeff Guinn has described the ways early incarnations of the Temple served the people of Indianapolis. The income generated through licensed care homes, operated by Jim Jones’ wife, Marceline Jones, subsidized The Free Restaurant, a cafeteria where anyone could eat at no cost.

Church members also mobilized to promote desegregation efforts at local restaurants and businesses, and the Temple formed an employment service that placed African-Americans in a number of entry-level positions.

While it’s the kind of action some churches engage in today, it was innovative – even radical – for the 1950s.

In 1962, Jones had a prophetic vision of a nuclear catastrophe, so he urged his Indiana congregation to relocate to Northern California.

Scholars suspect that an Esquire magazine article – which listed nine parts of the world that would be safe in the event of nuclear war, and included a region of Northern California – gave Jones the idea for the move.

In the mid-1960s, more than 80 members of the group packed up and headed west together.

Under the guidance of Marceline, the Temple acquired a number of properties in the Redwood Valley and established nine residential care facilities for the elderly, six homes for foster children, and Happy Acres, a state-licensed ranch for mentally disabled adults. In addition, Temple families took in others needing assistance through informal networks.

Sociologist of religion John R. Hall has studied the various ways the Temple raised money at that time. The care homes were profitable, as were other moneymaking ventures; there was a small food truck the Temple operated, and members were also able to sell grapes from the Temple’s vineyards to Parducci Wine Cellars.

These fundraising schemes, along with more traditional donations and tithes, helped underwrite free services.

It was at this time that young, college-educated white adults began to trickle in. They used their skills as teachers and social workers to attract more members to a movement they saw as preaching the social gospel of redistribution of wealth.

My younger sister, Annie, seemed to be drawn to the Temple’s ethos of diversity and equality.

“There is the largest group of people I have ever seen who are concerned about the world and are fighting for truth and justice for the world,” she wrote in a 1972 letter to me. “And all the people have come from such different backgrounds, every color, every age, every income group.”

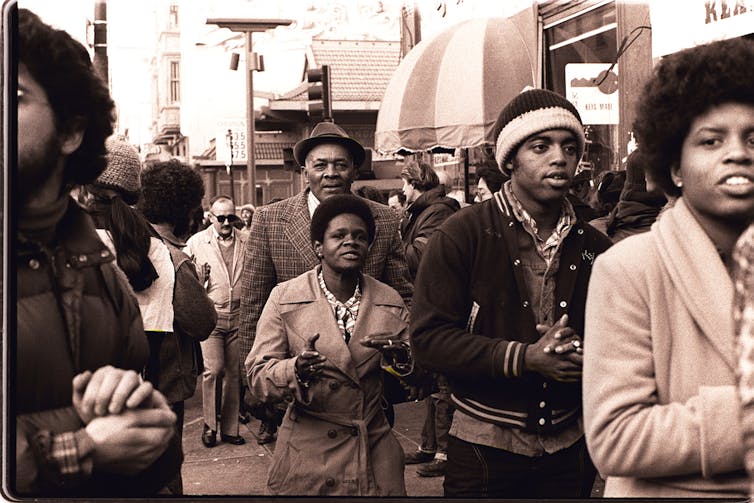

But the core constituency comprised thousands of urban African-Americans, as the Temple expanded south to San Francisco, and eventually to Los Angeles.

Frequently depicted as poor and dispossessed, these new African-American recruits actually came from the working and professional classes: They were teachers, postal clerks, civil service employees, domestics, military veterans, laborers and more.

The promise of racial equality and social activism operating within a Christian context enticed them. The Temple’s revolutionary politics and substantial programs sold them.

Regardless of the motives of their leader, the followers wholeheartedly believed in the possibility of change.

During an era that witnessed the collapse of the civil rights movement, the decimation of the Black Panther Party and the assassinations of black activists, the group was especially committed to a program of racial reconciliation.

But even the Temple couldn’t escape structural racism, as “eight revolutionaries” pointed out in a letter to Jim Jones in 1973. These eight young adults left the organization, in part, because they watched new white members advance into leadership ahead of experienced, older black members.

Nevertheless, throughout the movement’s history, African-Americans and whites lived and worked side by side. It was one of the few long-term experiments in American interracial communalism, along with Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement, which Jim Jones emulated.

Members saw themselves as battling on the front lines against colonialism, as they listened to guests from Pan-African organizations and from the recently deposed Marxist Chilean government speak in their San Francisco gatherings. They joined coalition groups that were agitating against the Bakke case, which ruled that race-based admissions quotas were unconstitutional, and demonstrating in support of the Wilmington Ten, 10 African Americans who were wrongfully convicted of arson in North Carolina.

Members and nonmembers received a variety of free social services: rental assistance, funds for shopping trips, health exams, legal assistance and student scholarships. By pooling their resources, in addition to filling the collection plates, members received more in goods and services than they might have earned on their own. They called it “apostolic socialism.”

Living communally not only saved money, but also built solidarity. Although communal housing existed in Redwood Valley, it was greatly expanded in San Francisco. Entire apartment buildings in the city were dedicated to accommodating unrelated Temple members – many of them senior citizens – who lived with and cared for one another.

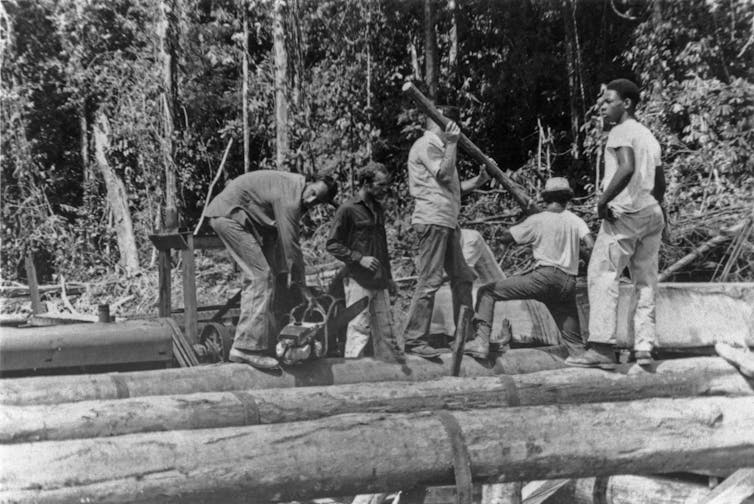

As early as 1974, a few hardy volunteers began clearing land for an agricultural settlement in the Northwest District of Guyana, near the disputed border with Venezuela.

While the ostensible reason was to “provide food for the hungry,” the real reason was to create a community where they could escape the racism and injustice they experienced in the United States.

Even as they toiled to clear hundreds of acres of jungle, build roads and construct housing, the first settlers were filled with hope, freedom and a sense of possibility.

“My memories from 1974 till the beginning of ‘78 are many and full of love, and to this day they still bring tears to my eyes,” recalled Peoples Temple member Mike Touchette, who was working on a boat in the Caribbean as the deaths were occurring. “Not only the memories of building of Jonestown, but the friendships and camaraderie we had before 1978 is beyond words.”

But Jim Jones arrived 1977, and an influx of 1,000 immigrants – including more than 300 children and 200 senior citizens – followed. The situation changed. Conditions were primitive, and though the residents of Jonestown were no worse off than their Guyanese neighbors, it was a far cry from the lives they were used to.

The community of Jonestown is best understood as a small town in need of infrastructure, or, as one visitor described it, an “unfinished construction site.”

Everything – sidewalks, sanitation, housing, water, electricity, food production, livestock care, schools, libraries, meal preparation, laundry, security – had to be developed from scratch. Everyone but the youngest of children needed to pitch in to develop and maintain the community.

Some have described the project as a prison camp.

In several respects that is true: People weren’t free to leave. Dissidents were cruelly punished.

Others have described it as heaven on earth.

Undoubtedly it was both; it depends on who – and when – you ask.

But then there is the final day, which seems to erase all the promise of the Temple’s utopian experiment. It’s easy to identify the elements that contributed to the final tragedy: the anti-democratic hierarchy, the violence used against members, the culture of secrecy, the racism, and the inability to question the leader.

The failures are apparent. But the successes?

For years, Peoples Temple provided decent housing for hundreds of church members; it ran care homes for hundreds of mentally ill or disabled individuals; and it created a social and political space for African-Americans and whites to live and work together in California and in Guyana.

Most importantly, it mobilized thousands of people yearning for a just society.

To focus on the leader is to overlook the basic decency and genuine idealism of the members. Jim Jones would have accomplished nothing without the people of Peoples Temple. They were the activists, the foot soldiers, the letter writers, the demonstrators, the organizers.

Don Beck, a former Temple member, has written that the legacy of the movement is “to cherish the people and remember the goodness that brought us together.”

In the face of all those bodies, that’s a difficult thing to do.

But it’s worth a try.