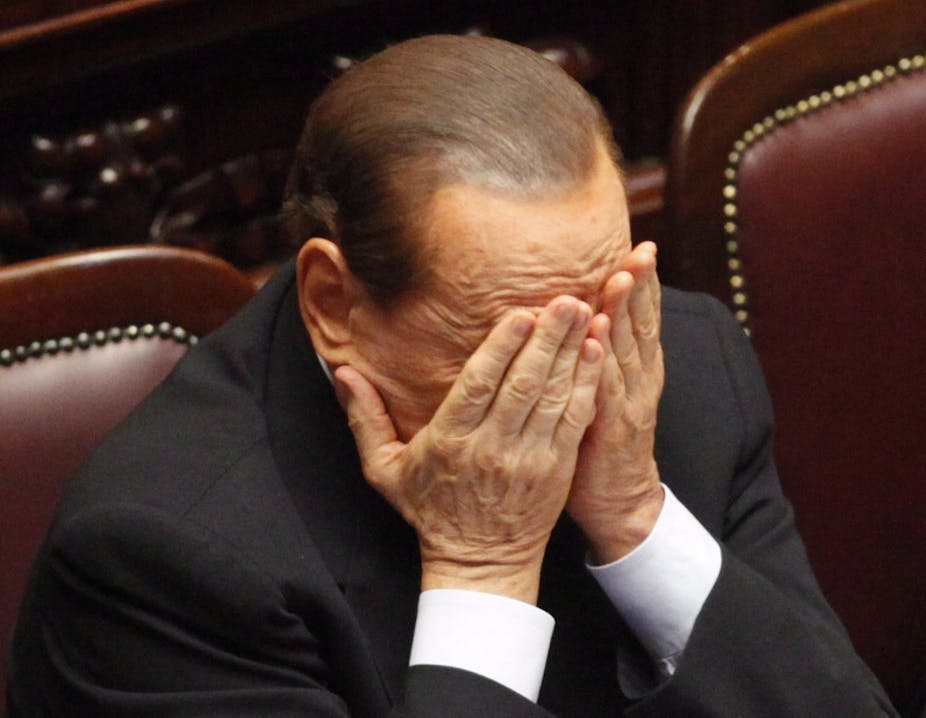

Italy’s sovereign debt crisis has been overshadowed by Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi’s reluctant promise to resign after the country’s parliament made clear he no longer commanded a majority.

Italy, a country regarded as “to big to fail”, has a public debt of 1.9 trillion euro – 120% of its gross domestic product (GDP) – and is haunting the Eurozone countries and world markets in ways that dwarf the concerns over Greece.

After the sovereign debt attention shifted from Greece to Italy, Berlusconi found it impossible to convince the world, the markets and most importantly, his coalition partners, that anything less than his resignation could help to salvage the economy.

Berlusconi framed his departure – if that is what it truly becomes – in such a way that he would go only after the latest “stability” pact measures were accepted by the parliament, thereby obligating the opposition to accept some nasty austerity measures.

Nonetheless, Berlusconi’s departure marks a line in the sand and possibly the end of an era. At play in this current scenario were not only Italy’s economic woes but also the powerful obstacle of the presence of the leader himself.

Part of Italy’s economic problems were political, and more specifically, could be blamed on leadership. Berlusconi, who is known around the world as a media tycoon and wealthy businessman, entered politics in the 1990s and quickly surged to political prominence.

In 1994 he assumed the position of Prime Minister, where his eight-month tenure was brought to an end in similar circumstances to those he is experiencing today.

He has been in power on three separate occasions. The latest mandate dates back to 2008, when he convincingly defeated the centre-left large and fragmented coalition.

Berlusconi has ruled with great controversy and erratic behaviour. On the whole, he failed to bring to the Italian economy the reforms he promised would make it more competitive. He was especially reticent to deal with its large public expenditure and narrower revenue stream.

Berlusconi has also been distracted by his personal quandaries which included alleged acts of corruption, bullying of the judiciary, sexual scandals, and conflicts of interest.

His government operated at times like a company board of directors, with himself as CEO. At other times his conduct was aptly reflected by the comparison made by Giovanni Sartori, prominent Italian political scientist who compared Berlusconi’s form of government to a “Sultanate” with a pool of slavishly loyal “yes” men and a line of beautiful harem inhabitants.

In defiance of these campaigns against him, Berlusconi tried to capture the high ground and complain that he was the most persecuted man in history. Constantly at odds with ongoing anti-corruption investigations, which Berlusconi has claimed involved 2,500 requests for court appearances and a cost of Euro 250 million in legal expenses, his departure may well unleash an army of new trials and allegations now that his immunity could disappear.

Amid the global financial crisis, Berlusconi acted with complacency and arrogance, believing that Italy was immune from the crisis. When the economy was targeted for its structural debt status, he cried “foul”. He was at pains to state that Italy’s economic management was stringent, that primary public debt was declining and that Italy’s economy was performing better than many in the Eurozone.

The equity and bond markets remained unconvinced and they pushed for greater assurances and commitments from the centre-right government which could not come.

Assuming Berlusconi resigns after the acceptance of the new budget proposals as he promised, the choices facing the country are just as daunting as they were during his reign. While Berlusconi’s failure to govern the country and his loss of credibility within the markets raised the stakes – his removal from the scene is not a guarantee that this volatility will disappear.

Another centre-right government led by a Berlusconi “stooge” has already been proposed which will only further annoy markets’ confidence. Italian President Giorgio Napolitano will have a significant say in the aftermath and the options include a temporary technical government, much like what was seen in the 1990s, or the less-likely option of early elections.

Some claim that a prominent contender for leader of the technical government option is Mario Monti, the former EU competition commissioner and Rector of Milan’s Bocconi Business School. But the truth is anybody’s guess and interesting times are afoot in this country yet again.

Read more:

As Berlusconi exits, is democratic reform the next real step for Europe?