John Büsst earned the moniker “The Bingil Bay Bastard”. From his self-built homestead in Bingil Bay, he campaigned from the early 1960s against grazing and agricultural industries seeking to fell the tropical forests of north Queensland.

Then, in his words, “in came the Army” eyeing “the best, most scientifically valuable, and the very loveliest” low-lying forest areas surrounding Mission Beach for army weapons testing. By 1968, after a campaign opposing the tests, nearly 50,000 acres of this land had been protected. Eventually, nearly 100,000 acres would become national park.

Review: John Büsst: Bohemian artist and saviour of reef and rainforest – Iain McCalman (New South)

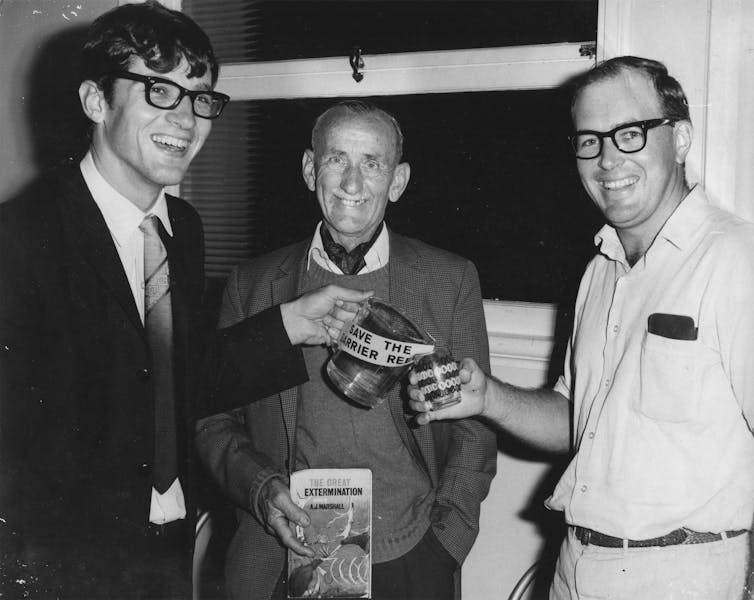

Büsst embraced the “bastard” epithet when he helped lead the movement to save the Great Barrier Reef from mineral, oil, and gas exploitation. In 1967, he read in the local newspaper that a nearby, offshore reef (Ellison Reef) was the subject of a mining lease to extract its coral lime, which was presumed dead, for fertiliser.

By 1968, that local skirmish had grown into an international conservation campaign to protect the reef from oil and gas development, embroiling scientists, conservationists, politicians, oil companies, trade unions, and the media in a seven-year struggle.

The campaign ended in 1975 after a trade-union black ban, a four-year joint Commonwealth and Queensland Government Royal Commission into the exploration and drilling for petroleum on the reef, and a High Court challenge to determine whether states of the Commonwealth held sovereignty over Australia’s “territorial seas”.

The reef was ultimately protected in 1975 under the auspices of the newly formed Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Much of this was thanks to Büsst’s endless campaigning from Bingil Bay. Büsst, however, had died in 1971 – so he didn’t get to see the final fruits of his labours. His friend and journalist, Barry Wain, wrote, in a moving obituary, that “compromise was not part of his [Büsst’s] approach.”

The title of the obituary was “The Bingil Bay Bastard”. But that nickname, although written with a sense of endearment, creates an image of a man calloused with cynicism and filled with a rigid, uncompromising, almost uncomfortable, determinism.

In Iain McCalman’s book, John Büsst: Bohemian artist and saviour of reef and rainforest, we come to know Büsst as a loving brother, aspiring artist, social drop-out, eventual conservationist, and a humorous and cherished friend.

McCalman, a master biographer of the eccentric, bold, and brilliant figures of history, has given us a much needed picture of Büsst. His book breathes humanity back into a man who fought to protect the world he lived in and loved.

Büsst deserves to be more well-known within Australian circles. I believe part of the reason why few people know of him is because he appears so sparingly in the historic record.

Born to privilege

I first came across Büsst in James Bowen and Margarita Bowen’s 2002 history of the reef, then again when I turned to their sources, Patricia Clare’s The Struggle for the Great Barrier Reef (1971), and the poet Judith Wright’s classic re-telling of the Save the Reef Campaign, The Coral Battleground (1977).

His role within the Save the Reef Campaign of 1967-1975 was paramount to its success, but has perhaps been drowned out by the more prominent people he worked with, most notably Wright.

Born in 1909 in Bendigo, Victoria, Büsst was raised to follow his father’s footsteps into law and business. Sent to board at Wesley College, he befriended the future prime minister Harold Holt. (The two remained close till Holt’s drowning in 1967.) But unlike Holt, Büsst had dropped out of university, devastatingly for his parents, to become an artist.

Büsst helped create and lived in the Montsalvat artists’ colony in the Melbourne suburb of Eltham before leaving and heading to another artist colony on Bedarra Island (off the coast of Mission Beach). After that, he settled in the nearby coastal village of Bingil Bay, where he launched his environmental campaigns.

While most will read McCalman’s book for details on the rainforest and reef campaigns, for me, the pages devoted to Büsst’s earlier life provided the most intrigue. In many ways, he remains somewhat at arms’ length in these sections because the historical archive is relatively shallow when it comes to these years.

Yet, McCalman pieces together Büsst’s early life, adolescence, short-lived university days, his time as a Meldrumite (a collection of artists led by the Max Meldrum), and at the time of Büsst’s joining, painter and sculptor Colin Colahan), and then as an active member of the Montsalvat artist colony. The image we get of Büsst, at times, is of a naive, rich-boy who became swept up in the bohemia of 1930s Melbourne.

However, by the time he moved north to Bedarra in 1940 (with his sister Phyl) Büsst was a seasoned and skilful builder and far more self-assured. He was lured to Bedarra after the relationships at Montsalvat became strained.

But at Bedarra too, McCalman shows the most significant struggles, apart from living through tropical summers in makeshift dwellings, were the personality conflicts between Büsst and his fellow island dwellers. A constant relief were the visits from his friends, such as Harold and Zara Holt.

It was at Bedarra where Büsst became interested and nearly obsessed with nature and the science of ecology. This new interest was largely instigated by CSIRO and University of Queensland scientists who had begun to visit Bedarra, other nearby islands, and the forest of the adjacent mainland, to study the birds and plants dwelling there.

In particular, Len Webb, an ecologist within the CSIRO’s Rainforest Ecology Unit (and whose story featured in McCalman’s book The Reef), taught Büsst how to understand the connectivity between land and sea, rainforest and reef, and the politics of scientific institutions and research. The pair also enjoyed a life-long friendship.

Nonetheless, frustrated with the challenges of island life, Büsst and his wife Ali, moved to Bingil Bay. It is at this point where the book, Büsst’s life, and the historical archive shift in intensity.

A vivid retelling

Armed with a new sense of ecological understanding, Büsst would fight to protect the rainforests surrounding Mission Beach and the reef. The former’s importance to the nation’s history feels diminished compared to the significance of the reef’s protection.

But McCalman reminds us the rainforest is Djiru Country. McCalman includes the history of displacement of the Djiru Traditional Owners and the imprisonment of many on Palm Island, which had been designated a “reserve” in 1914. He adds that in 2011 when the Djiru gained Native Title rights, they included “7000 acres of rainforest […]” rescued from the army by Büsst in 1967.

This is a powerful reminder that history is felt, often most crucially and materially, at a local and familial level.

My own summary of Büsst’s life is banal compared to McCalman’s vivid prose. His book provides an essential retelling of the Save the Reef campaign through Büsst’s experience of it.

McCalman is a great teller of stories and Büsst becomes a full-figured character within this one. He was a man who loved nature, but also people, and it was his ability to connect with others, from all walks of life, that helped him in his environmental campaigns.

McCalman writes that when Webb first met the Büssts, Webb taught them ecology and they opened his eyes to the “North Queensland Paris”: a multicultural, multi-ethnic, dynamic world of cutters, millers, farmers, painters, and writers.

Apart from giving fresh perspective to Büsst’s life, McCalman gives an equally rich telling of the connectivity between North Queensland people, their cultural and social threads, and their deep pride in, and love for, the places in which they live. If there is a tragedy to Büsst’s life, it is what happened to him in his later years when he became more isolated and that connection to people began to vanish.

In battling his environmental campaigns, he had become estranged from his wife Ali. Additionally, a lifetime of smoking and a tendency towards heavy drinking had rotted his teeth and left him with throat cancer. As the reef came under the purview of the Royal Commission, Büsst became too ill to travel south to be part of the proceedings, and he was essentially alone in Bingil Bay.

When his death was announced to Ali, his sister Phyl, Webb, and his other conservation comrades, they flew back north to commemorate him.

A major theme of McCalman’s book is connectivity. Towards the end, he asserts that the

interconnected ecosystems of the Great Barrier Reef and the Wet Tropics Rainforests are once again fighting to survive the long-term effects of human folly.

But it isn’t the environment that must save itself. Instead, he calls on new “artist-warriors and nature-saviours” and the politicians to protect our environments. We must recognise our own roles in environmental and global change.

Essentially, he calls on us to do what Judith Wright described Büsst as doing – a line now engraved on a plaque in Bingil Bay: to fight so that humans and nature might survive.