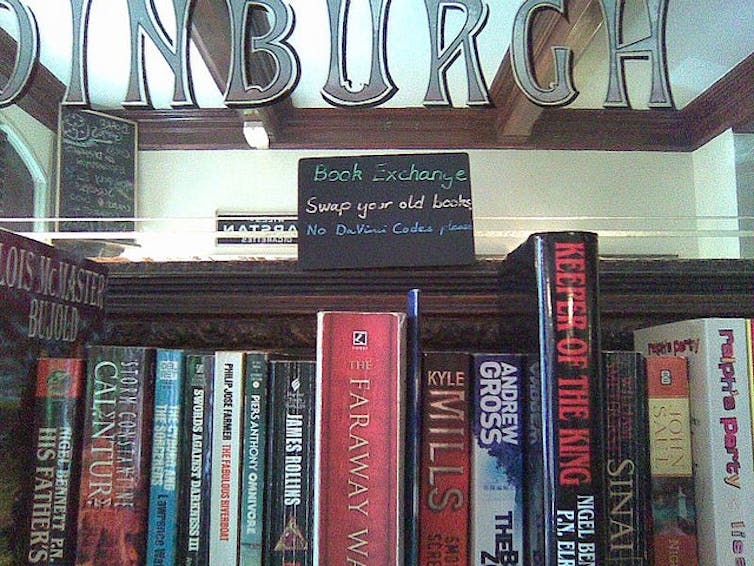

When you see almost complete shelves of abandoned copies of The Da Vinci Code and Fifty Shades of Grey in charity shops, their near total worthlessness seems to suggest that an individual copy of a book is worth very little. Every day libraries make decisions about the continued need for a given book. During collection weeding, titles that are old, little read or worn out are removed from circulation and are often thrown out.

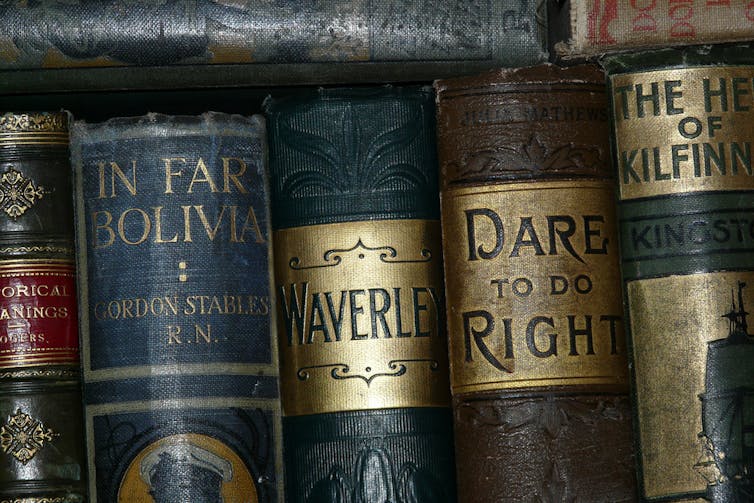

We do value a select sub-set of book copies. Book collectors, as well as university and state libraries, ensure that antique, rare copies of books are kept and preserved.

But what about the books that fall somewhere between Shakespeare’s first folio (worth at least $5 million) and a Dan Brown thriller with respect to rarity and financial value?

Do the books that fall in the middle all need to be stored indefinitely? Or are individual copies of no use as soon as a given title is digitised and freely available?

These are crucial questions for books that were published from the 19th century and into the early 20th century. Many books from this period are not considered valuable or rare enough for each individual copy to be spared from library culling. As more of these books are digitised, the argument for retaining dozens of copies in numerous libraries is harder to maintain and large numbers of individual copies are seemingly in danger of disappearing from public collections.

Book Traces is a new crowdsourced project that is collecting images of library books published between 1820 and 1923 that include marginalia and inserts. (The end date is the point at which books are usually still in copyright and therefore cannot be digitised.)

These are unique books that bear the “traces” of the people who read them, with inscriptions written inside, scrawled notes, or drawings on their pages. Others have objects stored inside, such as pressed flowers, locks of hair, or pictures.

One ideal requirement for submitted books is that they are part of regular library stacks and in circulation. Unlike books that have been deemed important enough to be protected by security staff and special collections reading rooms, these books could potentially be discarded, or lost, at any time.

Images uploaded to date include a child’s copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland held at the University of Virginia Library, which includes the former child owner’s earnest musings on the subject of blue jays. A copy of The Letters of Hannah More to Zachary Macauley from 1860 has a sewing needle and thread inserted into its endpapers. And clearly there once was a bored girl reading The Complete Works of Walter Scott who placed her paper doll clothes inside.

The site is part of NINES (Networked Infrastructure for Nineteenth-Century Electronic Scholarship), which is directed by Professor Andrew M. Stauffer at the University of Virginia. As the project site explains, there is “a prevalent assumption in library policy circles that copies of any given nineteenth-century edition are identical” and that “digital surrogates” can adequately replace multiple copies of printed books.

As the examples already collected on the site are beginning to show, these unique books “constitute a massive, distributed archive of the history of reading, hidden in plain sight in the circulating collections”.

A needle carefully driven through a book’s endpapers reminds us of how the act of reading was embedded in daily life in the 19th century, especially for women, whose leisure time was limited. The paper doll’s clothes in the works of Scott shows us that the boundary between books for children and books for adults was once much more fluid.

The written traces of readers of the past contain their responses to the books themselves, information about their lives, as well as records of major social and political events.

A reader of Vernon Lee’s Louis Norbert: A Two-Fold Romance expresses his or her discontent with the depiction of an American character: “How ridiculous & unjust, – why not take an English peasant or illiterate with no cutting & have him say the line”.

Jane Chapman Slaughter’s copy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Poems and Ballads is transformed throughout with multiple reflections on her lost beloved, John Adamson: “You read this, July 1st, Sunday, the day you said—‘goodbye,’ sitting in the great armchair in the Infirmary parlor—O friend of mine!”

During the American civil war, a copy of The Lives of the Popes by Leopold Von Ranke was looted from the home of a rector by soldier John G. Morrison, and was inscribed by the thief:

Taken from the house of the rev’d Jas. A. Harrold* Falls Church Fairfax County, Virginia Late rector of St. Andrews Free Church, Washington Now in the Rebel service 30th N.Y.S.V. Upton Hill. *October 5th, 1861

Is every 19th-century book worth preserving? For each one that bears a fascinating inscription or material trace of the past, like those being virtually collected on Book Traces, there are dozens of other obscure titles with many duplicates that will rarely ever be lifted from the library shelf.

Yet this project is a timely reminder that we ought to look inside each and every book before considering its destruction.

While we clearly don’t need to preserve every hastily discarded copy of the most recent paperback blockbuster, it is also true that printed books have much to tell us about the history of reading and the lives of readers and the worlds they inhabited. One scanned copy on Google Books can never be a substitute for the stories that unique 19th-century books can tell.