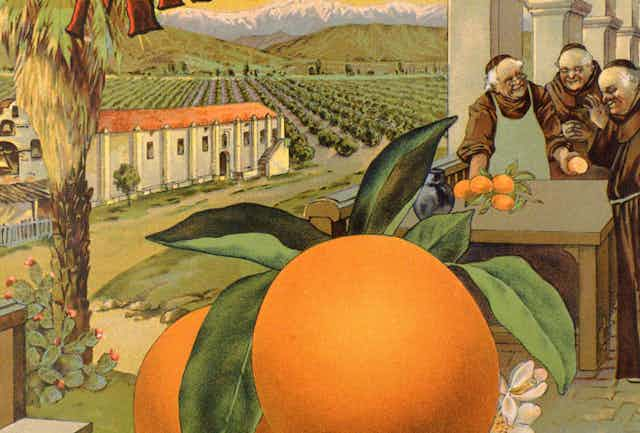

Images of orange groves and Spanish-themed hotels with palm tree gardens filled countless pamphlets and articles promoting Southern California and Florida in the late 19th century, promising escape from winter’s reach.

This vision of an “American Italy” captured hearts and imaginations across the U.S. In it, Florida and California promised a place in the sun for industrious Americans to live the good life, with the perfect climate.

But the very climates that made these semitropical playgrounds the American dream of the 20th century threaten to break their reputations in the 21st century.

In California, home owners now face dangerous heat waves, extended droughts that threaten the water supply, and uncontrollable wildfires. In Florida, sea level rise is worsening the risks of high-tide flooding and storm surge from hurricanes, in addition to turning up the thermostat on already humid heat. Global warming has put both Florida and California at the top of the list of states most at risk from climate change.

My books and research have explored how these two states were sold to the U.S. public like twin Edens. Today, descendants of those early waves of residents are facing a different world.

Selling semitropical climates

As railroads first reached Southern California and the Florida peninsula in the 1870s and 1880s, land, civic and newspaper boosters in each state worked to overturn beliefs that people only thrived in colder climes. In the decades after the Civil War, white Americans living in the North and Midwest had to be persuaded that sun-kissed climates would not do them more harm than good.

Employed by the transcontinental railroads, influential writers like Charles Nordhoff contested eastern notions of Southern California as barren desert where “Anglo-Americans” would inevitably succumb to the “disease” of laziness.

Challenging persistent ideas of a malarial swampland, promoters in Florida, including the state’s own Bureau of Immigration, similarly put a growing emphasis on climate as a vital resource for fruit growers and health seekers.

Climate became integral to California’s and Florida’s growing reputation as idealized U.S. destinations. Moreover, it was deemed unlike other natural assets: an inexhaustible resource.

Tourists and settlers gave weight to these claims. “The drawing card of Southern California,” a tourist from Chicago visiting Pasadena wrote in the Chicago Tribune in 1886, “is the beautiful, even climate.” Peninsula Florida was “blessed by nature with a semi-tropical climate,” a visitor wrote in the Atlanta Constitution in 1890. He saw its destiny to attract those who would “bask in the sunlight of a genial clime.”

This proved a compelling vision. In the 1880s, both Southern California and eastern Florida saw booms in settlement and tourism. Southern California’s population more than trebled during the decade to over 201,000, while peninsular Florida’s doubled to over 147,000.

Affluent white Americans weighed up the merits of each: for citrus-growing, winter recuperation, land investment. The differences were, of course, numerous. One state was western, the other southern; one more mountainous, the other flat. Some boosters critiqued their subtropical rival’s climate.

Southern California was too arid, a writer in the Florida Dispatch claimed, a desert “parched for want of water.” Florida, meanwhile, had too much of the stuff, editorials in California replied: a wetland fit for reptiles but potentially deadly to new residents who would wilt in its torrid summers.

Yet Southern California and Florida became connected through economic futures founded upon climate promotion and related industries of citrus, tourism and real estate. If rivals, they shared distinct market ambitions.

“California and Florida can [together] control the citrus trade,” the Los Angeles Times declared in 1885, arguing for mutual benefits in the promotion of oranges. The pair had much to gain from persuading Americans to eat their fruit.

Developers in both also changed the landscape by rerouting water to create communities in once-inhospitable places. In California, the spread of irrigation to turn “desert into garden” enabled the growth of citrus towns such as Riverside, while vast aqueducts conveyed water to thirsty cities like Los Angeles.

In Florida, flawed schemes sought to “reclaim” – essentially drain – wetlands, including the Everglades, where boosters like Walter Waldin sold Americans on a once-in-a-lifetime “opportunity to secure a home and a livelihood in this superb climate.”

An inexhaustible resource

The roaring ‘20s saw a new influx of sun-seeking, automobile-driving Americans drawn by boosters to the beaches and orange groves of Los Angeles County and South Florida.

Comparing Florida and California had become a national pastime as popular as mahjong and crossword puzzles, according to Robert Hodgson, a subtropical horticulturist at the University of California, in 1926.

Hodgson traveled to Florida to act as a judge at an agricultural show in Tampa where, the Los Angeles Times reported in a dig at Florida, he visited everything “from the dizziest pink stucco shore subdivision to the latest aspiring farming colony reclaimed from the alligators.”

Snipes aside, climate and the lifestyle they offered to middle-class Americans set Southern California and Florida apart. Hodgson wrote that they were similarly “blessed by the gods” through a “joint heritage of something like 90% of the subtropical climatic areas of the United States.”

Climate, moreover, was unlike other natural resources. Whereas precious metals or forests could be mined or cut down, climate was different: an infinite resource. It “can never be exhausted by man in his ignorance or cupidity,” he explained.

Climate as crisis

This history of climate-based advertising puts into stark relief the challenges faced by California and Florida in the era of climate crisis.

Today, both confront recurring natural disasters that are exacerbated by human-caused climate change: wildfires in California, hurricanes and flooding in Florida, and increasingly dangerous heat in both.

Extensive home-building in wildfire and coastal zones has compounded these risks, with insurance companies now refusing coverage for properties at risk of fires or storm damage, or making it prohibitively expensive.

Once marketed successfully as the United States’ two semitropical paradises, Southern California and Florida now share disturbing climate-influenced futures.

These futures bring into question how historic visions of economic growth and the sun-kissed good life that California and Florida have promised can be reconciled with climates that are no longer always genial or sustainable.