The latest migration statistics released in late November showed immigration figures were at a “record high” and were reported as such in the press. Though not a statistically significant increase from 2015, net migration stands at 335,000 – consisting of 189,000 EU citizens and 196,000 non-EU citizens settling in the country, and 49,000 British citizens emigrating in the year ending June 2016. For the first year, Romania was the most common country of former residence, accounting for 10% of all migrants.

On the evening these figures were released, a rather unedifying, though telling, spat occurred on the BBC’s Question Time programme. A primary school teacher made a number of points about English not being the main language heard in the playground, airing concerns about integration. He said:

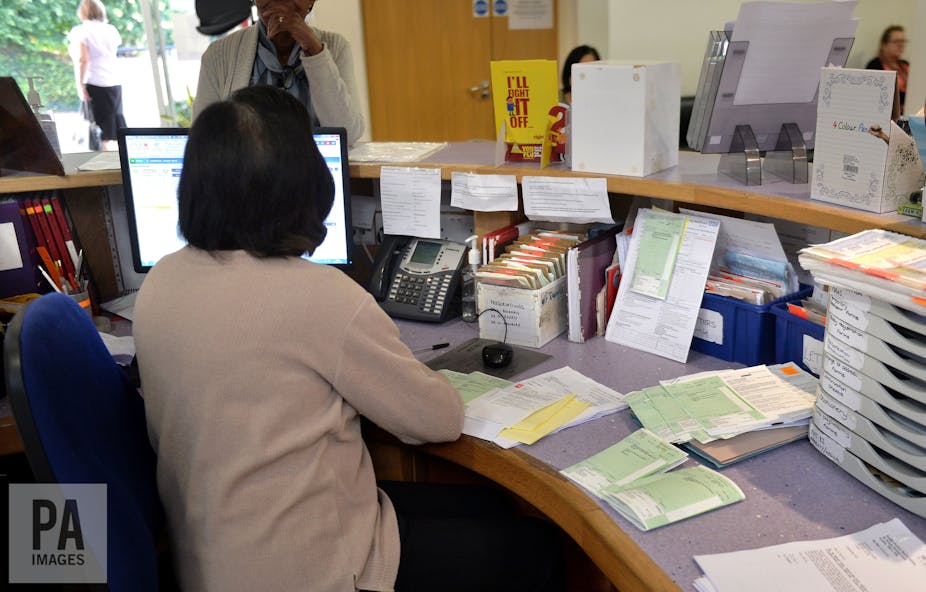

When you get a massive influx of people all coming at the same time, that’s what people have a problem with. That’s when we get concerned when we go to the doctors and we can’t get appointments, when we go down to A&E and it’s full.

If concerns about integration and changing cultures is one strand of popular concern about migration, the strain upon public services is the second. Lest we forget, this concern about migrants placing a strain on public services played a key role in arguments made by the Leave campaign ahead of the referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU, and the call for limiting freedom on movement in Europe. As lead Brexiteer Boris Johnson himself suggested during the campaign:

We get uncontrolled immigration, which puts unsustainable pressure on our vital public services.

So the complaint that migrants are placing an intolerable strain on public services is likely to be part of the conversation on migration in the UK for the foreseeable future. But, as I argue in a forthcoming paper in the journal Population and Development Review, this strain on public services is more a result of the political-ideological choice of austerity than about the number of people who need to use public services.

Cuts crippling public services

Various studies have demonstrated the net, macroeconomic benefits of migration to the UK. In the past ten years, the population of the UK has grown by some four million (or around 7%) to around 65m, primarily powered by immigration.

Tying these two themes together, a 2014 study found that EU migrants made a net fiscal contribution of £20 billion between 2001 and 2011 – a quarter of this from migrants from the “A10” countries of central and Eastern Europe. Sound management of public services could have seen the increased returns to the exchequer stemming from this growth from taxes and improvements in productivity be reinvested in providing sustainability for public services. This, of course, is rather the opposite of what has happened.

A growing population and an ageing population does not automatically conjure up a vision of less demand for public services. However, the across-the-board cuts under the 2010 coalition and 2015 Conservative governments have inevitably placed tremendous pressure on existing services. Recently, for example, the FT estimated that local government budgets have been cut by 19% between 2010 and 2015, with 150,000 pensioners losing access to vital services over the same period. While spending on the NHS is increasing, much of this is swallowed up by the costs of inflation and rising prices. Cuts plus population growth plus population ageing as an equation usually results in a simple, logical end point: that the UK’s public services are perceived to be at breaking point.

New figures from NHS England analysed by the BBC put this point into sharp perspective: in 2015-16, 475,000 patients waited more than four hours for a bed on a ward, an increase of nearly fivefold in five years. This has been blamed by NHS executives on “growing demand” on the system.

Migrants have been a convenient “whipping boy” for successive governments of all political hues with only a handful of politicians and journalists presenting them as net contributors to the country. So it is little surprise that the negative consequences of austerity have seen migrants used once again as a scapegoat. What we are seeing, therefore, is the unravelling of public services not because of an unsustainable level of demand, but precisely because of a break in the contract between a state and all of its taxpayers to provide a sustainable level of supply.

I like that Britain is an ever more varied, vibrant, multicultural society. On the other hand, I think I have the wherewithal to both accept and understand why others might not share my view. But, fair’s fair. If you can’t get a GP’s appointment, or if the council is moving to monthly dustbin collections, this is not really the fault of a Ioan, or a Teodora or a Matias. This is really rather the fault of a Dave, a George and, perhaps, a Theresa. To a degree, it’s also the fault of a Tony and a Gordon for not properly setting out the positive economic case for migration. Blame them, not the migrants in our neighbourhoods.

It has been argued that austerity is the “greatest bait and switch in history” – an advertising scam by the state. Pinning the blame on migrants for the effects of austerity only serves to make the deception even more intolerable.