We all care, at some level, about our planet and for our children. And yet, ample research has proven that we are doing a terrible job of guaranteeing a healthy future for either of them.

In my work as an interdisciplinary scholar who has researched children’s rights, the social determinants of child development and the psychology of climate change, I have come to believe we must give more credit to young people for their ability to contribute to society. If we could learn to understand communities through the eyes and voices of children our approach to global warming might drastically change.

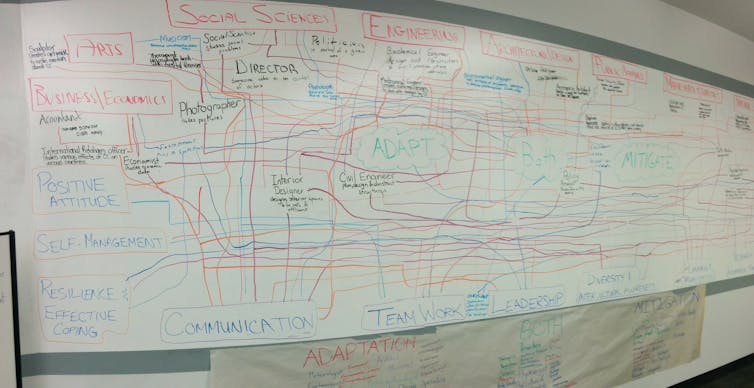

For this reason, I have designed and led university-exposure experiences for high school students focused on career development and responding to climate change. In each workshop, I have seen students’ energy and pride as they imagine and see themselves impacting our shared future.

Non-governmental organizations such as UNICEF have argued that children and youth are perhaps the most powerful weapon we have to restore planetary health and yet they are underutilized.

This might be largely because most adults believe young people are unable to contribute to this world in any meaningful way.

Adults rarely think of children as a resource in the fight against climate change. In other words, we disempower children just by believing that their potential is limited. Sadly, as a result, children themselves think the solution to climate change is in someone else’s hands,typically the government or the private sector.

Loris Malaguzzi, an Italian educator who pioneered a transformative approach to early childhood education, talks about the concept of the “Hundred Languages of Children,” meaning they have multiple ways of seeing the world. It is we, the adults, who are limited in our ability to understand. Thus, it is our responsibility to learn their many languages.

Both vulnerable and competent

Being able to engage young people more effectively in talking about global warming and giving them a stage for their meaningful contributions might be what we need to successfully address the global challenges climate change brings.

There’s lots we can learn from the field of children’s rights that teaches us how to empower children for significant and long-lasting changes that eventually lead to positive gains for all of us. To do so, however, we must accept one of the basic and fundamental principles at the core of the children’s rights approach: respect for the young person who is acknowledged to be both vulnerable and competent.

By accepting children’s vulnerabilities we commit to protect and nurture them as they develop skills they need to lead healthy, productive and fulfilling lives. By accepting their competence, we commit to offer children age-appropriate opportunities to safely express their views and be taken seriously when making decisions about matters that are important to them.

In other words, to empower children means to nurture them as they develop the skills they need to take charge of their lives.

Better career guidance

Career guidance and education may offer us a unique opportunity to empower youth at a critical time in their lives. At the same time, it can prepare tomorrow’s workforce to think more deeply and critically about jobs and the environment, and how these can help restore the health of our planet and contribute to our physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual survival.

However, while career guidance and education is part of the standard secondary school curriculum across all Canadian provinces, the training teachers receive to become a guidance counsellor in Canada has been judged as insufficient except for in Québec, where teacher’s training meets standards for career development that align with requirements of the International Association for Educational and Vocational Guidance.

Research shows that in Ontario schools, guidance counsellors do not receive adequate career development training and they also spend only about one-quarter of their time dealing with career counselling (academic issues take up about half their time).

This evidence points to the fact that career guidance and education in secondary schools may be a missed opportunity.

While teachers’ training is a key consideration for improvements in career guidance and education, the students’ experience could also be improved by making required career courses more personally meaningful.

By approaching this course from a children’s rights perspective the students would be nurtured and supported at a key time in their development when they are making a choice about their future professional lives.

Students would learn about the careers of their own interest, the role that such work would play in the bigger picture of planetary health and they would be counselled to reflect on how their professional choices could make this planet healthier.

We cannot expect that everyone will want to become an environmentalist or an activist, but we can expect that the children of today will want a future for their own children, and therefore they will also want the best for our planet. We only need to show them how the two are connected through the work they will do.