Charles Dickens’ first biographer, John Forster, ended The Life of Charles Dickens in 1874 with the Dean of Westminster’s sermon. This was delivered in Westminster Abbey on June 19 1870, three days after the novelist’s funeral. Dickens’s grave in Poets’ Corner would, said the dean:

henceforward be a sacred one with both the new world and the old, as that of the representative of literature, not of this island only, but of all who speak our English tongue.

In the century and half since his death, writers from the southern hemisphere have continued to recast Dickens’s fictions in new forms. Two novels – Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs (1997) and Lloyd Jones’s Mr Pip (2007) – rework Dickens’s Great Expectations (1859-60).

In so doing, they present readers with opportunities to rethink ways in which Dickens was “a representative of literature”; including the power relations around class and colonialism that have shaped the transmission of writing in “our English tongue” for the past two centuries.

Altered expectations

In Jack Maggs, Carey – a double Booker Prize-winning Australian novelist – rewrites Great Expectations from the perspective of a convict who returns from his sentence in the new world to terrible risk: the only sure thing that old England can offer him is a noose. Dickens’s original novel sees the world from the shifting perspective of Philip Pirrip – or “Pip” – an orphan boy plucked from obscurity who thinks he has been “made” by the wealthy Miss Havisham. In fact his fortunes have been advanced by Abel Magwitch, a convict who the young Pip had helped in an escape bid.

In Carey’s pastiche, Magwitch becomes Jack Maggs, who has survived transportation to Australia and become a successful and wealthy brickmaker. He returns from the British colony of New South Wales to the London of 1837, the year during which Dickens rose to fame. Maggs wants contact with Pip – rendered here as the young man Henry Phipps, whom he has made into a gentleman.

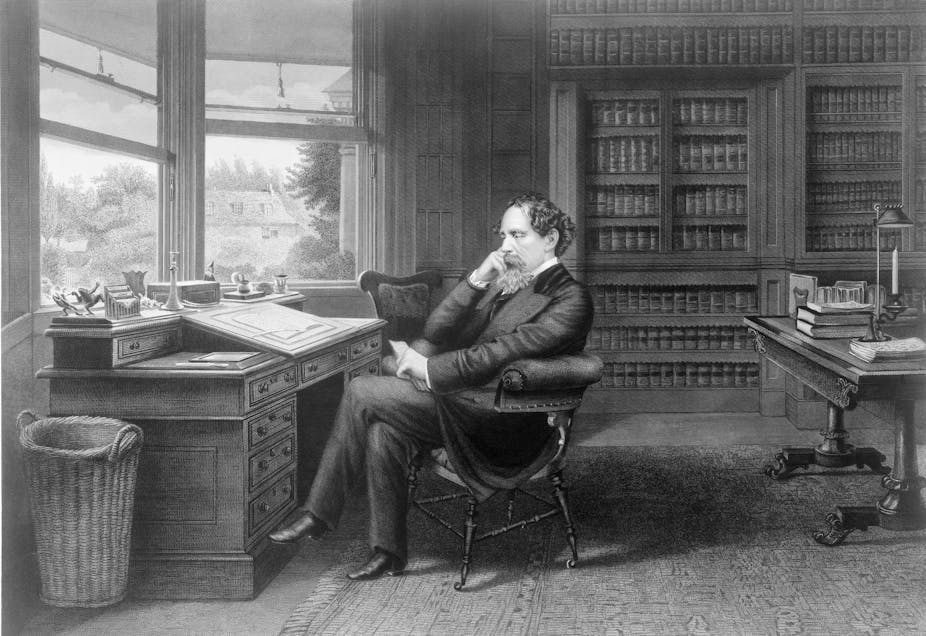

Instead, he encounters the young, upwardly mobile novelist Tobias Oates: ambitious, anxious to hold onto the new respectability he has secured after childhood poverty, and riddled with emotional and financial insecurities. Oates is of course a version of the young Dickens prior to the consolidated public image of the respectable literary giant commemorated in Forster’s biographical portrait.

Carey reminds us, through Oates, that the Dickens of 1830s closely observed a London world of crime and sexual misdemeanour that could scarcely be rendered in the language of fiction available to him. Dickens also flirted with the new science of mesmerism, a technique which Oates applies to Maggs to exorcise him of the “phantoms” or traumas of brutalised convict life. Oates thereby appropriates Maggs’s story as a series of “burgled secrets” which are to be recast as a crime melodrama for his own literary gain.

Yet Carey reverses this invasive power relation and enables Maggs to tell his own story, restoring him to his own emotionally scarred but resilient origins. Carey concludes with the image of Maggs as redeemed Australian subject who has exorcised the phantoms of English class longings, and is restored to his family in the new world.

Pip in the Pacific

Lloyd Jones’s Mr Pip transports Great Expectations to the Pacific, the conflicted island of Bouganville in Papua New Guinea. The New Zealand novelist writes about the reading and interpretation of Dickens’s novel among a group of black children and their eccentric, self-appointed white teacher, Mr Watts, as an event punctuated by the rebel insurgence, military occupation and horrific violence experienced in the 1990s.

If Dickens wrote Great Expectations as a tale of betrayal, guilt and ambiguous origins in 1860, Jones’s novel shows how that moral and emotional frame can be adapted to new, post-colonial conditions. Matilda is Jones’s 14 year-old fatherless narrator, who comes to appreciate that Pip’s story of mobility and self remaking, which the migrant Mr Watts reads to his pupils as a source of inspiration, is powerfully apt for those whose lives are subject to displacement and migration.

But the “Pip” that Matilda venerates by writing his name, in shells, on the beach is mistaken by military occupiers as the name of a rebel who is being concealed by the villagers. In a terrible unfolding of misunderstandings, both Matilda’s mother and Mr Watts are butchered.

As Matilda escapes to a life of education and possibility, reunited with her migrant father in Australia, she comes to realise that the Great Expecations that Mr Watts read to them was in fact an abridged format for the children of empire: that Dickens’s “sacred” text existed in multiple versions.

Jones’s story casts powerful new light on the way in which Dickens can be seen as a leading “representative of literature”. In one sense, Dickens was the great author of Forster’s biography, buried in Poet’s Corner. In another, as Matilda comes to recognise, the name “Dickens” helped to drive and commodify the global transmission of Victorian literature in many different formats to many new parts of the globe.

As Regenia Gagnier’s research on the global circulation of Dickens and other Victorians shows, literature itself is always in a process of migration to and through new power relations.