With the Productivity Commission Report into Early Learning and Childcare due this month and ABS data on the subject released last week, the cost of childcare is in the spotlight again. However, highlighting the dominance of cost, rather than considering its overall benefits to individual children, families and Australian society, is missing the point.

Many arguments can be mounted for the benefits of quality early childhood education and care. Evidence drawn from longitudinal research of children who have access to quality early childhood education and care includes: better school success; a decreased crime rate; less substance abuse and increased long-term employment.

However, in purely economic terms, does the cost outweigh the benefit? This should be the question driving the Productivity Commission inquiry.

The ABS data: what does care cost?

The ABS report details the cost of childcare as a net cost of care to parents after benefits have been taken into account. “Formal care” is approved and registered care that includes centre-based or family day care. Informal care is that provided by family members or unregistered carers.

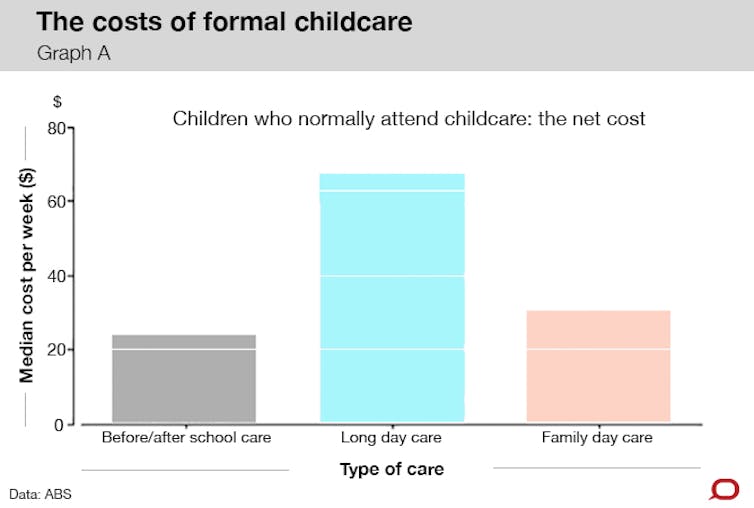

For the majority of children who usually attended formal care (63% or 544,500), the usual net cost was less than $80 per week. Long day care costs were typically higher than for other forms of care, with the median cost at $67 per week (Graph A). A large majority of children (92% or 1.3 million) who usually attended informal care did so at no cost.

It is not surprising that the Coalition instigated its Inquiry into Childcare and Early Learning in a “productivity” arena for there is evidence that access to quality childcare makes a difference to female participation in the workforce. This inquiry has the potential to inform policy decisions that may alter the directions of Australian early childhood education for many years to come.

What is the connection to productivity?

It has taken a while, but many countries have become aware of the relationship between childcare, women’s participation in the workforce, and gross national product (GDP). The Grattan Institute report into strategic planning to improve Australia’s economic status recommends:

Governments should concentrate their limited resources for economic reform where they can have the greatest impact on Australian prosperity.

One of the three reform strategies the report recommends is to increase female participation in the workforce as a means to lift Australian productivity.

If Australian women did as much paid work as women in Canada – implying an extra 6% of women in the workforce — Australia’s GDP would be about $25 billion higher.

The links between women’s participation in the workforce and GDP are clear. A major impediment to achieving this participation is the cost and availability of quality childcare.

A lack of investment in early learning

History is not comforting here. Despite the body of research showing the benefits to the economy, to families and to young children, Australia’s record regarding the provision of quality, accessible and equitable early childhood education and childcare is not good. Although there are many world-class Australian early childhood programs (as we have world-class universities and schools), the access to quality is not equal and is becoming more expensive.

What will it take to convince policy-makers of the need to increase public investment in early childhood care and education? Will the submissions to the Productivity Commission inquiry make a difference? The 463 submissions and 729 comments on the website are indicative of the public discourse in this country.

Many submissions are individual pleas for better access to childcare. Others (e.g. AIFS) present long-term, large-scale Australian research on the importance of quality early childhood education.

There are many risks associated with treating all evidence submitted to this inquiry as equal. The analysis of the submissions must treat the body of evidence of the benefits of quality early childhood education and care submitted by researchers differently to evidence submitted by individuals or lobby groups.

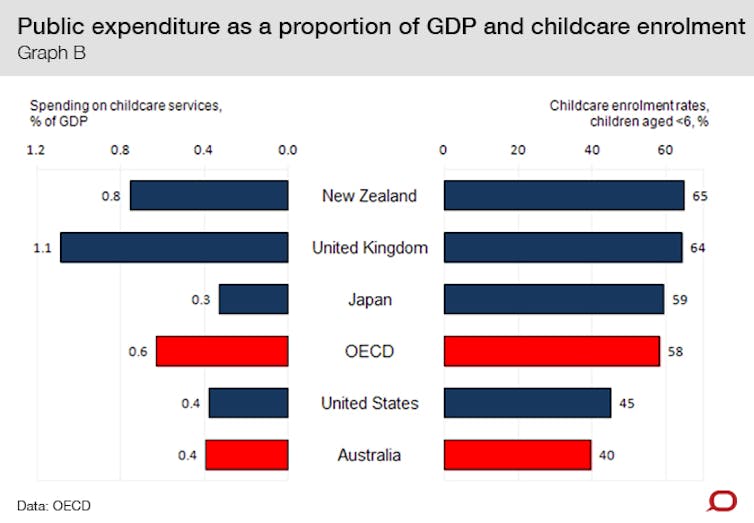

What would happen if evidence led Australian education policy decisions regarding our youngest children? Government investment would be at the same level as other OECD countries that lead the way in long-term educational outcomes (e.g. Finland). The proportion of spending on early childhood education related to GDP would be equal to, or exceed that, of other OECD countries.

The questions about whether early childhood educators need to be qualified would cease. Early childhood education would be seen as the foundation of a democratic, civil society rather than a service only some can afford.