The growing labour movement in China, as fragmented and repressed as it is, offers hope for workers everywhere as an example of organising and protecting themselves against incredible odds.

Independent labour organising and independent trade unions are banned and workers do not have the legal right to strike. But millions of workers have organised autonomously and staged “wildcat”, or unofficial, strikes, with the main union charged with representing Chinese workers either absent or side-lined in recent industrial actions.

In fact, Chinese workers most often organise without any help from the main Chinese union: the powerful All-China Federation of Trade Unions.

The world’s largest trade union

Founded on May Day 1925, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) is the only legal trade union federation in China and, with a membership of 280 million in 2014, the world’s largest.

ACFTU branches are compulsory and union membership automatic in many companies. This inflates its membership, even though many branches exist without the awareness of employees. And “members” don’t exercise any democratic control over ACFTU affiliates. In fact, the ACFTU serves mainly as an extension of the Chinese state, which appoints the union’s top leadership. Its provincial and municipal leaders also simultaneously retain government positions. Hardly any union leader has prior experience of labour organising.

The international labour movement is divided over whether or not to engage with the ACTFU, with some activists insisting dialogue with the union must remain open. But a closer examination of recent events in China suggests that there is very little chance that the ACFTU can be reformed. To understand why, we need to appreciate the transformation of the Chinese working class.

From work units to wildcat strikes

In the Mao era from 1949 to late 1970s, workers were organised into work-units, which provided education, housing and pensions to workers and their families. Many workers were entitled to lifetime employment. They were not won by the union, which acted to distribute benefits and encourage production. Disparities still existed and workers organised protests by themselves, most notably by apprentices and temporary workers during the Great Leap Forward of 1956-1957 and again at the height of the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1967.

China’s embrace of market reforms since the late 1970s has thoroughly transformed conditions for workers. As the reforms gradually dismantled the welfare regime of the work-units and opened up the private sector for domestic and foreign investment, workers were left largely to fend for themselves.

However, the ACFTU failed to protect state-sector workers from mass redundancy and migrant workers from low wages, excessive overtime and employment insecurity. Private companies routinely ignored labour regulations, and industrial accidents were commonplace. As a result, labour disputes shot up dramatically in the 1990s.

In response, the government introduced a series of new laws to channel workers’ grievances but their implementation remains limited and uneven.

The ACFTU has come under considerable pressure to reform. In the last two decades, it has begun to experiment with collective consultation and unionisation of the private sector. One well-known case is the unionisation of Chinese Walmart workers, which was initiated by workers but aided by the ACFTU. However, it has proved to be mainly about manoeuvring against foreign companies than a genuine desire to change the poorly paid and highly insecure employment conditions of Walmart workers.

In the end, these efforts have been shown as half-hearted and ineffective. They have not strengthened workers’ collective interests or made the ACFTU more relevant to the Chinese workers.

Independent labour organising and independent trade unions are banned and workers do not have the legal right to strike. Despite the bans, workers have held “wildcat” or unofficial strikes, without any involvement from the ACFTU.

In May 2010, 2000 workers at Honda auto part suppliers went on a strike for higher wages, better conditions and a union election. The initial strike shut down all four of Honda’s assembly plants in China, and triggered more than 100 secondary strikes in nearby plants. The workers won huge wage rises despite the plant union openly supporting management.

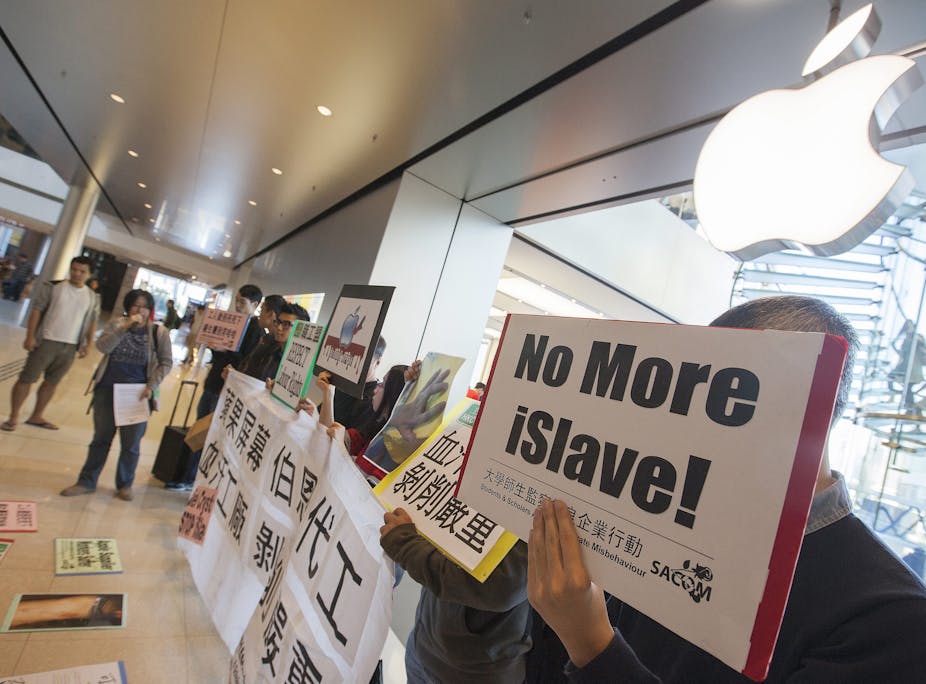

At Foxconn in 2010, more than a dozen workers attempted suicide by jumping off the windows of their dormitory. While exploitation of migrant workers is well known, the suicide of so many workers still shocked the public. Subsequently, workers at several Foxconn plants went on strike on their own over conditions. But, again, the ACFTU played very little role in this process.

Recently, another huge strike took place at Yue Yuen, the largest shoe manufacturer in the world, in the city of Dongguan. In 2014, about 40,000 workers demanded higher pay and better pension contributions for their retirement. Again, the trade unions were absent.

It is worth pointing out that municipal and provincial affiliates of the ACFTU did sometimes step in during a strike to help bring about a speedy resolution by mediating between employers and striking workers in negotiations. But once the strike was settled, the union affiliates quickly withdrew from the factory, with strike-leaders left unprotected and usually dismissed.

Economic downturn

Although it is still too politically risky to organise independent trade unions, labour activists have forged informal networks and accumulated organising experience over the years, especially in the large industrial zones. The activists are aided by China’s labour non-government organisations (NGOs), many of which emerged in the 1990s.

The growing strike activities have taken place during a rapidly growing period, where industrial employment is abundant and the unemployment rate very low. However, the Chinese economy has begun to slow down since the Global Financial Crisis, and last year recorded the lowest rate since early 1990s. Workers face an increasingly uncertain future in a slowing economy, and a difficult political environment that constrains their organising capacities.

Nevertheless, this has not deterred workers from taking collective actions, as evident in the rise of strikes in 2014 and 2015. The labour movement is gaining pace China, against all odds.

This is part of an ongoing series on the waning power of Organized Labor. Click here to see other articles in the series, which culminates on May 1, International Workers’ day.