Corruption is thought to cost China US$86 billion each year. Widespread corruption at all levels of Chinese society also worsens economic inequality, which could potentially lead to social unrest.

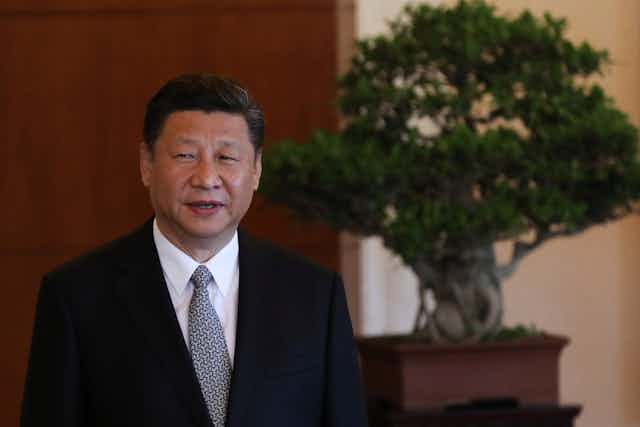

Although no one doubts the importance of efforts to curb graft, anti-corruption campaigns under the leadership of Chinese President Xi Jinping have been controversial.

A number of state, administrative and party authorities with overlapping powers currently share the task of fighting corruption. The most powerful of these are the Communist Party of China (CPC) Disciplinary Inspection Commissions (jiwei). And the most feared tool in their arsenal is shuanggui, which orders Communist Party members to a particular place for questioning and investigation.

In practice, shuanggui is sometimes a secret and often indefinite detention mechanism. It has reportedly used torture and other illegal means to extract confessions.

Although the use of shuanggui is not without support among the general populace, it breaches most of the “due process” principles in Chinese law. These include the presumption of innocence, access to legal counsel, rules on evidence, open trials and, most importantly, no deprivation of personal liberty without due process.

There are also questions as to the legality of the Communist Party authority exercising policing and semi-judicial powers. But a recent move by the party to establish a new government branch to fight corruption is likely to cause even more controversy. It has far-reaching consequences in terms of rule of law, and checks and balances.

The proposed change has received little coverage outside of China. This is unfortunate given its strategic role in the anti-corruption campaign and potential need for constitutional amendments.

A new state power structure

In November 2016, the Communist Party issued the Pilot Programs for Reforming the State Supervision System in Beijing, and Shanxi and Zhejiang Provinces.

The initiative is designed to create a so-called supervision commission by merging all existing anti-corruption authorities into one. This new authority, supplied with additional powers to ensure “full coverage”, will be responsible for investigating and handling all alleged misconduct and crimes committed by officials exercising public powers.

The commission will be vested with various police and semi-judicial powers, from interrogation to freezing property and detention. The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (SCNPC) adopted a decision to implement these programs in December 2016.

The exercise of these powers by the new authority clashes with existing anti-corruption authorities, which may lead to inconsistencies with existing laws on governing authorities and procedure. The SCNPC’s decision has suspended the operation of the Administrative Supervision Law, and certain provisions of the Criminal Procedure Law, the Organic Law of the People’s Procuratorates, the Law on Prosecutors, and the Organic Law of Local People’s Congresses and Local People’s Governments, in the three pilot regions.

A new State Supervision Law has been proposed to expand the pilot programs nationwide. It is scheduled for discussion at the SCNPC in June 2017, and for adoption by the National People’s Congress in March 2018.

A respected guardian or fearful beast?

The People’s Congresses will create the proposed supervision commissions as a state power parallel to the executive and the judiciary. It will be a new branch of government and its establishment will be a major political and constitutional reform. But it’s unclear whether the Communist Party has any intention of making attendant constitutional amendments.

The CPC Pilot Programs, whose details are not public, have been widely reported in the Chinese official media. What’s known is that the supervision commissions will share personnel with the CPC Discipline Inspection Commissions under a “one entity with two names” arrangement.

Although the chairperson of the State Supervision Commission will be appointed by the National People’s Congress, she is to be nominated by the Central Committee of the Communist Party. In other words, the CPC Discipline Inspection Commissions – the party authority exercising shuanggui – will soon have two names.

This allows the conduct of Communist Party authorities to be legitimised by attributing their conduct to that of the supervision commissions. Nothing has been said by CPC or by SCNPC about how the supervision commission will exercise its powers.

It is also unclear whether secret detention, frequently used in shuanggui by the CPC Discipline Inspection Commissions without judicial oversight, will be abolished.

Consolidating the various authorities with anti-corruption functions into one state entity established by the legislature may ostensibly resolve the long-debated issue of whether the Communist Party may exercise police and semi-judicial powers. A state authority – the supervision commission with status defined by laws – will not only legitimise anti-corruption mechanisms and allow them wider coverage, it will also streamline the process and promote efficiency and transparency.

But an integrated entity of the state and the Communist Party in the “one entity with two names” arrangement – without clear demarcation of powers – means it’s unknown whether and how the new body will act according to the law.

Because the new branch will be a state entity of significance, many Chinese scholars have already asserted that it’s in violation of the Chinese constitution for the SCNPC to implement the Communist Party’s pilot programs and to suspend national laws without approval of the National People’s Congress.

If the power of the new authority is not clearly defined and limited, due process is unlikely to be protected. A new institution with unprecedented powers will likely undermine the rule of law and create fear, rather than order.

A Chinese constitutional model?

The new anti-corruption mechanisms are to form part of the “China model” – improved governance capacity under the strict control of the Communist Party – that President Xi aims to achieve.

But the establishment of the supervision commission clearly demands major constitutional revisions, as it is to add a new branch of government – a power parallel to the executive and the judiciary.

While there are far too many unknowns about this change, we do know that the new constitutional authority will be an integrated entity of the party and the state. This is exactly the kind of entity Deng Xiaoping tried to get rid of at the end of the Cultural Revolution.

The Chinese Communist Party is nowadays said to be “within the law, under the law, as well as above the law”. But by once again integrating the party and state power, the new reform is worrying from the perspective of the rule of law.