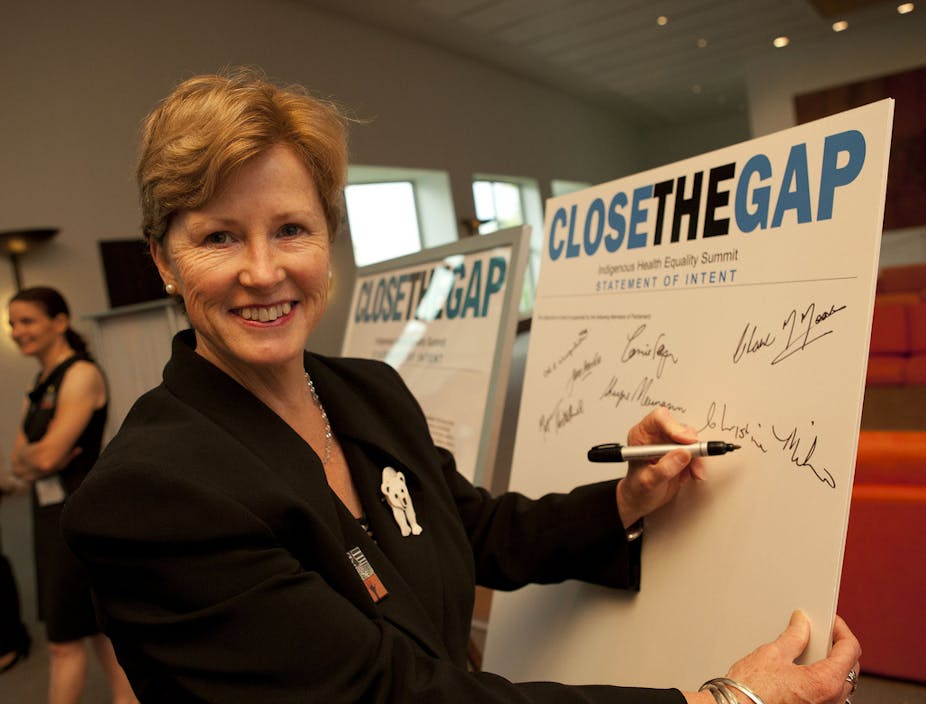

Christine Milne, Senator for Tasmania and leader of the Australian Greens, was a crucial part of the Multiparty Climate Change Committee that designed Australia’s Clean Energy Future package. Since taking over from long-time leader Bob Brown earlier this year, Senator Milne has focused on business and on rural and regional communities - not the Greens’ traditional strong points.

David Bowman, Professor of Environmental Change Biology at the University of Tasmania, spoke with Senator Milne about climate change, the triple bottom line, a new economy and whether there is really any point to the Greens.

David Bowman In two years time, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will be about 400 ppm. According to the Greens’ policy documents, the world should have an atmosphere with 350ppm. Many scientists think that we now probably have crossed very major thresholds which will have all sorts of unforseen and possibly unforseeable consequences. So really the question for a politician is, how do you prosecute your case if your opponents don’t believe in that?

Christine Milne Well, we continue to do so, but it is extremely frustrating to know what you do know and to take the science seriously and to have people say to you that it’s wildly exaggerated, it’s not true, and so on, when they haven’t even tried to read the science. They’ve made a decision to reject or ignore the science because it suits their world view.

Denialism has much more to do about values and world view than it has to do with actually understanding the science. So we should have been using the social sciences a lot sooner than we have been to work out ways of talking to people’s value systems rather than to their intellectual capacity.

I went through a period where I became deeply despondent about the consequences of what’s going on with global warming, and my rational mind said to me, it’s too late, that we’re on a trajectory for four to six degrees of warming. But 350ppm is much better than 450; we argued the point through the Multiparty Climate Committee, because the $23 price is based on a 550ppm trajectory. If we’d gone with 450, the price would have been over $50, and they wouldn’t even countenance the idea of doing any Treasury modelling around what a price would need to be to deliver 350.

So I went through a very bleak phase of thinking we’re just not going to make it as a planet - well, the planet will make it, but how humans survive and how ecosystems survive is another thing. And I’ve gotten through that by just simply taking the view that one has to keep arguing for it and doing everything we can, because it will be better than it otherwise would have been. Your optimism has to be there. Maybe we will gain momentum if enough people get to that point.

David Bowman How do you articulate a vision when, as far as I can tell, everything at the moment is about the fear of debt, the fear of costs, and - because it’s rained - it seems in Australia that climate change has just disappeared? You’re trying to take on two almost impossibly difficult arguments at once. One is to convince people of the seriousness of the global change problem. [The other is] an alternative economic model which just doesn’t seem to have any political support from anybody out there.

Christine Milne In terms of the new economy, the problem in Australia is that it’s almost impossible to bring about a change in the order of things when the vested interests fight like partisans to keep their vested interests in place. Those who believe in the new order are only lukewarm in their support of the new order. [As Machiavelli says], humankind doesn’t believe in new things until they’re actually delivered.

When I took over the leadership, one thing I wanted to do was to build a constituency in progressive business. For the first time in Australia we now have a critical mass of businesses - most of them small and medium-scale businesses but nevertheless a critical mass - which depend collectively on embracing a low-to-zero carbon economy: everything from architects designing green buildings, new building product, town planners, energy efficiency, the renewables space to environmental health.

But they are terrified to speak out. They’re all terrified that if they speak out, and there is a change of government, that they will be punished accordingly, and that they will fail to gain access. That the government programs which benefit them - for example, the renewable energy target or the like - will be significantly changed to their detriment.

David Bowman A lot of people talk about - disparagingly - green tape, as being a barrier to investment and possibly a barrier to innovation. How can the Greens deal with those tensions of a mixed economy, of the state knowing best, versus the fact that the market is able to find novel solutions?

Christine Milne It’s going to be a mixture always. Where we’ve gone wrong - the global financial crisis - it occurred not because of over-regulation but because of deregulation. There is a place for regulation and there is a place for the market, and the Greens have argued that strongly. That’s why I support emissions trading and don’t support Tony Abbott’s direct action plan - it just won’t deliver.

I am totally opposed to this nonsense of green tape. That is just a clever use of words to imply that environmental regulation is somehow hindering the ability to do business. Environmental regulation is actually protecting what is a public asset in the interests of the community. And what you’ve got business now doing, where they’re trying to get rid of environmental regulation, it’s because they want to do things which clearly are unsustainable.

We will be campaigning strongly coming into the Federal election to maintain levels of environmental protection that are consistent with the challenge of the century: sustainability. It is about slowing down the extraction of non-renewable resources and making the use of those non-renewable resources more efficient by pricing them more effectively.

David Bowman: Are Green parties logical? Wouldn’t it be ultimately better not to have a Greens party but just to have very strong environmental principles in all political parties? Do you see the Greens as just a transitional stage, rather than really a significant new development politically?

Christine Milne We have said for years that if the others became serious environmentalists then there would be less appeal as far as a Greens party is concerned.

But actually I think it’s become a fundamental difference. The Liberal and Labor parties in the Australian context - but it’s pretty much similar globally - emerged at a period when the Earth was free. There was a view in both sides of politics that the planet had an infinite capacity to give up resources, and an infinite capacity to absorb waste.

The politics emerged out of who should maximise the benefit from the transition of those free resources and dumping into atmosphere and ocean. Conservative parties took the view that those who owned the capital - the capacity to transform - had more of a right to the profits. And the workers became organised on the basis that they had a reasonable right to a share in the profits. But they are both taking the view that the Earth is free and infinite.

The Greens emerged in the 1970s, when there was beginning to be strong recognition that the Earth was not infinite in its capacity to give up resources or absorb waste. Out of that came the Brundtland Report. They came out of [the Brundtland process] basically saying there are only two real things - people and nature - and it is the interaction of those two that have to be sustainable. Economic tools have to better guarantee a sustainable relationship between the two.

How did we end up with economics suddenly having equivalence with people and nature? Brundtland went to the World Bank, and when it came out of the World Bank it came out as a triangle. Then you always had society and economy trading off against environment. And that has been the politics out of the whole sustainability debate for the last 20 years of the last century and the first decade of this one.

For the Greens, the sustainability of the planet as a home for us is central. You protect your environment as the basis for a sustainable society, one that is just and peaceful and so on. For both the Republicans and the Democrats in the US, for the Coalition and Labor in Australia and the same in the UK, the environment is just an add-on, they don’t get it as a central, absolutely underpinning feature.

The other parties do not have the same philosophical view or even a philosophical view about the environment underpinning everything else. They’re never going to be able to approach these issues with the integrity the Greens do and that’s why the Greens are growing this century.

David Bowman What is the balance between aspiration and ideology versus the pragmatics of politics? Do you think the Greens really want to be in these balance of power situations? Isn’t it a much more ideologically pure state to just be outside and having visions of how the world could be, rather than the grubby mechanics of how the world is?

Christine Milne Getting balance of power is much more important because you can actually deliver outcomes. The only reason we’ve got a clean energy package implemented in Australia is because the Greens got balance of power in both houses in the Federal Parliament last election. Both major parties went into that election saying they were not going to price carbon in this period of government, and it was only because of the agreement with the Greens that the Multiparty Climate Committee was set up and that we got the outcome that we did.

This is the first time in Australian politics where we’ve actually implemented what I would call an ecological financial arrangement. We are pricing pollution at $23 a tonne. People who had a $6000 tax-free-threshold, now it’s $18,200. Now there’ll be an awful lot of students around Australia and a lot of people working part time who probably didn’t earn more than 30-odd thousand or maybe 35 working part time, they will now get $18,000 of that tax free. So what a good outcome for the planet! We start getting pollution down and we start getting the pressure taken off people who are trying to make a different contribution.

The periods outside balance of power are when you do the work on the policy detail so that the minute you are in a position to implement it you actually know what to do.

David Bowman Tony Abbott seems to be staking his political credibility on the fact that he wants to abolish the carbon tax. So isn’t that a high-risk - because what would be the global significance of that, if these achievements are actually ultimately turn out to be reversed?

Christine Milne Well, it would be a terrible setback for a transition to a low-carbon, zero-carbon economy if the whole clean energy package was reversed, not only in Australia but yes I think there would be a significant flow-on effect - people around the world would throw up their hands. But you see I don’t think it’s going to happen.

The trouble for the Coalition is, where are they going to get the money? They say they are committed to a 5% reduction in emissions and they say they’re going to do it with their direct action plan. Now they’ve already said they’re not going to pursue the mining tax, so that’s going, and they’re not going to charge polluters for the pollution. So where is Tony Abbott getting the money from to pay the polluters?

The latest poll is saying people are going, “what was all that [the carbon tax uproar] about then? It hasn’t affected me at all, much”. Abbott has changed his position in the last couple of weeks and the focus is now not so much on carbon pricing, it’s gone back to “can you trust the government?”. So it’s gone back to integrity issues rather than carbon pricing because he’s not making way on carbon pricing. So I don’t think you’re going to see the Coalition going into next year without having significantly changed its position.

I think that many of the reforms we’ve achieved in this period of government - things like the Parliamentary Budget Office - those kinds of reforms will stay, and they’re there because of the Greens.

David Bowman So almost in conclusion, you’re arguing that the Greens are a reformist party rather than a revolutionary party?

Christine Milne Absolutely, we’re a reformist party. We’re going back to basics in terms of what is real on the planet. People and nature are real, the rest are constructs. Those constructs can be changed, and economic tools have to be changed in order for people and ecosystems to survive.

The full transcript of David and Christine’s interview is available here. In addition to what you’ve read, they discuss: genetically modified crops; land grabs in the developing world; how locally based agriculture can provide food security; uranium mining and nuclear waste disposal; how Tasmania could have (and maybe still can) provided a model for a post-resource Australia based on brains and high-quality products; how the tax arrangements from the clean energy bills are funding green buildings; the Coalition’s quiet backdown on the NBN; and how convening a panel of experts can help a government change its mind while saving face.