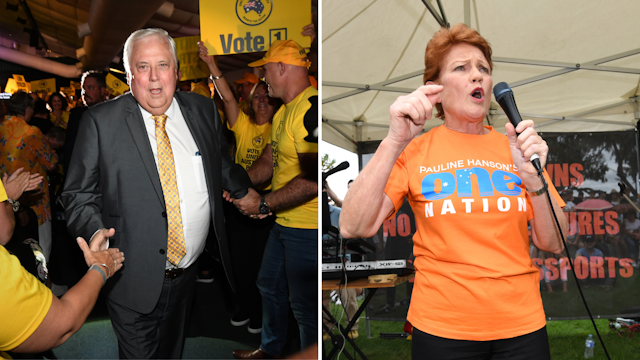

Many commentators tipped Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party (UAP) and Pauline Hanson’s One Nation to perform well this election by scooping up the “freedom” and anti-vax vote from voters angry about how the pandemic was handled.

But this wasn’t the case.

The parties did see a modest rise in their vote, but not enough to translate into significant electoral success. Neither party won any seats in the lower house.

UAP candidate Ralph Babet is likely to pick up Victoria’s sixth Senate seat – in part thanks to preferences from the Coalition, who put UAP second on their how to vote cards in the state. But this may be all Palmer gets for his obscene campaign spending.

UAP leader and former Liberal MP Craig Kelly lost his seat of Hughes, and Palmer failed in his bid for a Queensland Senate spot.

One Nation also failed to pick up any extra Senate seats. Pauline Hanson is projected to hold onto her Senate seat, only just, while Malcolm Roberts continues as a Senator having earned a six year term in the 2019 federal election.

As a populism researcher, I’ve taken a keen interest in these minor parties. Here’s why I think they did so badly.

Read more: What actually is populism? And why does it have a bad reputation?

United Australia Party

UAP garnered about an extra 0.7% of the national primary lower house vote compared to 2019 (for a total of 4.1%), after spending an estimated A$70-$100 million. In Queensland the party has thus far secured just 4.3% of the Senate vote – and this is where Palmer himself was the lead Senate candidate.

While in 2019, the party didn’t have much of a platform outside of being anti-Bill Shorten, this wasn’t the case in 2022. They had visible policies on cost-of-living, such as housing affordability and investing Australian superannuation funds in Australian companies.

The party also tried to position itself as the voice of the “freedom” movement, opposing COVID lockdowns and vaccine mandates.

The fact that none of this seemed to resonate – particularly their interest rate policies – surprises me.

I expected the party’s populist, anti-major party, “freedom” agenda to resonate in some parts of the country. For example, many predicted UAP would poll well in the outer suburbs of Melbourne where there’s high levels of anti-lockdown and anti-Dan Andrews sentiment.

While it did poll better than it has before in some of these areas, it didn’t translate into electoral success, nor make much of a dint in preferences as it did last election.

One Nation

One Nation struggled despite fielding candidates in 149 of 151 House of Representatives seats.

The party’s national primary lower house vote increased a bit – up about 1.8% to 4.9% – but this was mostly because it ran in many more seats than last election.

Early in the Senate vote count it looked like Hanson might lose her Senate seat, but now she’s projected to just hold on.

She faced fierce competition from Palmer, former Queensland Premier Campbell Newman, and a relatively unknown minor party called Legalise Cannabis Australia. Hanson is very well known – particularly in Queensland – so it was also surprising to see her fighting for her political life against a little known party.

6 reasons why UAP and One Nation flopped

So why did both parties fail to perform as well as some thought they might? Here are some of the key reasons:

They were competing for the same small segment of the electorate. Both are populist right parties, they tried to brand themselves as the parties of the “freedom” movement, and likely took votes off each other in the process.

They were also competing for votes against the right wing of the Coalition, some of whose candidates share very similar views in terms of sentiments regarding immigration and vaccination mandates.

The wind has been taken out of the sails of the “freedom” movement. Since lockdowns finished and almost all COVID restrictions have been phased out, the cause is not as urgent. This freedom banner brought together disparate groups – spanning from the far-right to “wellness” and alternative health groups – but the links between the groups were always tenuous. Now the shared enemy of lockdowns has disappeared, there doesn’t seem to be social, class or political linkages holding them together. If this election was held last year – or even a few months ago – both parties might’ve had more success.

Populists often campaign against the “corruption” of the ruling classes. However, it was hard for UAP or One Nation to get much traction on this as almost every non-Coalition party or candidate – from Labor, to the Greens to the teal independents – was also campaigning on the same issue.

One Nation’s anti-immigration stance is one of its key policies. The fact that Australia had barely any immigration since the beginning of the pandemic made campaigning on the party’s bread-and-butter issue very difficult.

There’s been a lot of talk about parties using “microtargeting” in this election, but UAP’s strategy was the opposite. Their mass advertising and huge billboards were the modern equivalent to throwing a bunch of leaflets out of a moving plane. This election suggests this doesn’t work – you can’t just bombard people.

None of this means we should write UAP or One Nation off for good. Hanson has proven herself a mainstay of Australian politics, and returned from the political wilderness before.

Meanwhile, Palmer has now contested three separate federal elections – each time, seemingly with a completely different platform. With his deep pockets, who knows whether or what he will run on in 2025.

This federal election, however, was not a “populist moment” for these parties. The real story in 2022 is not on the right, but on the other side of politics.