The Sunburst attack uncovered in December 2020 illustrates the magnitude of the cybersecurity challenge. Hackers were able to breach some of the United States’ top government agencies as well as those of other organisations around the world by compromising updates from one of their software suppliers, SolarWinds. Organisations might make use of hundreds if not thousands of third-party suppliers and contractors through which they could be breached.

While many of these involve third-party suppliers and contractors in the IT realm, in some cases breaches can be caused by third parties that one might not expect. For example, it was reported in 2017 that a casino in Las Vegas was breached through an Internet-connected fish tank. Similarly, in 2014 Target was breached through its air-conditioning supplier. Organisations frequently take on new third-party suppliers and contractors, further compounding the challenge.

The rapidly evolving nature of the risk makes it difficult to assess, and all organisations are currently struggling with how to manage cybersecurity risk. New threat actors and types of attacks regularly emerge. For example, we are seeing the advent of AI-enabled attacks. In one highly publicised instance, cybercriminals tricked an employee into transferring money to them by using AI to imitate the CEO’s voice.

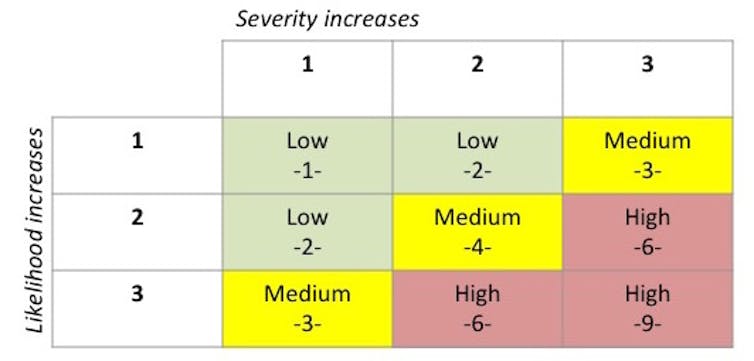

Current approaches to managing cybersecurity risk have significant shortcomings. Risk assessments tend to rely on “risk matrices”, which use a grid to compare the likelihood of the risk and the severity of the impact. The numerical values assigned to the likelihood and severity ratings tend to be ambiguous, meaning that they can assign the same numerical values to threats that are quantitatively quite different . This can cause organisations to incorrectly prioritise threats and thus allocate resources in a suboptimal manner.

A role for cyber insurance

Increased use of cyber insurance could significantly improve cybersecurity risk management. It helps organisations by transferring the risk to insurance providers. Quite importantly, it could also incentivize organisations to improve their cybersecurity levels, through insurers offering customers a discount in exchange for improving security measures.

Yet cyber insurance is still underdeveloped for a number of reasons. Insurers face difficulty in accurately assessing an organisation’s cybersecurity risk. Unlike in other domains that have similarly elevated levels of risk – such as pandemics – there is limited historical data to draw on. A contributing factor to this lack of data is that organisations are reluctant to disclose that they have been attacked due to reputational concerns. Moreover, an organisation’s risk profile at the time an insurance policy is issued may differ considerably several months later.

These issues are compounded by an acute shortage of experienced cybersecurity underwriters, whose job it is to decide whether to issue a policy to a prospective client.

Another challenge is “accumulation risk”, in which a single incident can spread to other parts of an insurer’s portfolio. It is particularly difficult to evaluate accumulation risk in the cyber realm. In the physical world, a hurricane or other natural disaster may trigger a surge in claims, but these claims are limited to a particular geographic area. In cyberspace, a cyberattack can result in claims around the world. For example, the WannaCry ransomware attack infected some 200,000 computer systems in 150 countries, severely disrupting major organisations such as FedEx and the UK’s National Health Service.

A related issue is “systemic risk”, in which one incident could cause a cascading failure that triggers the collapse of an entire system. For example, a cyberattack that takes down the power grid will impact sectors ranging from transport to communications to healthcare.

Improving our understanding of cyber risk

To address these issues, in our new book we propose a series of models aimed at helping both organisations and insurers manage cybersecurity risk. They make use of a methodology known as adversarial risk analysis, which makes it possible to better assess the risk that different threat actors pose to an organisation.

These models allow insurers to automatically adjust premiums in response to changes in an insured organisation’s cybersecurity risk. They draw on data provided by third party companies that gather real time information about organisations’ IT infrastructure, security products, and other factors to get a clearer picture of an organisation’s cybersecurity risk at any given point in time. These third-party companies include firms such as SecurityScorecard, Blueliv and BitSight.

One of the models makes it possible to better understand accumulation risk. It does so by breaking out different market segments as separate components in order to isolate, understand, and analyse the accumulation effect of a cyberattack on a given market segment.

The book also describes how some insurers are moving beyond merely selling insurance to assisting customers in improving their cybersecurity readiness. For example, they might share information on security vulnerabilities, assess customers’ IT infrastructure, or help them implement penetration testing of their IT systems and phishing-awareness campaigns aimed at their employees. In addition, they may support customers in responding to cyberattacks, providing crisis management and legal assistance, and helping them get back to business. This is typically accomplished through partnerships with cybersecurity companies, public relations firms and legal firms.

These developments can play an important role in cybersecurity risk management, helping make it possible to create a virtuous cycle where cyber insurance fosters an increase in cybersecurity worldwide.

This article is based in part on our latest book, Security Risk Models for Cyber Insurance, published by Routledge/Taylor & Francis. It grew out of a two-year project funded by the European Union under Horizons 2020, CYBECO (Supporting Cyber Insurance from a Behavioral Choice Perspective).

Created in 2007 to help accelerate and share scientific knowledge on key societal issues, the AXA Research Fund has been supporting nearly 650 projects around the world conducted by researchers from 55 countries. To learn more, visit the site of the Axa Research Fund or follow on Twitter @AXAResearchFund