In 1740, a modest squadron of ships from Britain’s Royal Navy departed Portsmouth in pursuit of an immoderate treasure. Commodore George Anson, who led the flotilla, was tasked with sailing south and west across the Atlantic Ocean, rounding Cape Horn, and interfering in imperial Spain’s lucrative trans-Pacific trade. But even before the mission got underway, its prospects of success appeared dubious.

A sizeable proportion of the roughly 2,000 sailors and non-seamen under Anson’s command lacked suitable experience. Worse still was the fact that so many of them took up their posts already in a parlous state of health. It is little surprise, therefore, that Anson’s “famous” voyage around the world proved to be, for most of the men who undertook it, a journey of no return.

Review: The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck Mutiny and Murder – David Grann (Simon & Schuster)

The crew of the Wager, one of the smaller of Anson’s men-of-war and the subject of David Grann’s latest book, were particularly unfortunate. By the time it approached the southern tip of Chile, the Wager had, like the rest of the squadron, repeatedly endured what Grann calls the “invisible siege” of shipboard illness: first typhus, and then scurvy.

Deprived of much of their manpower, the ships entered the so-called Drake Passage, a notorious stretch of ocean home to the strongest currents on earth. After several weeks plying those waters in severe weather, the Wager lost contact with Anson’s flagship and the rest of the fleet. Isolated in conditions inimical to navigation, the Wager managed nonetheless to sail around Cape Horn – but by that point its structural integrity was damaged and worsening.

Human error and irresistible storms conspired thereafter to drive the ship toward Patagonia and into a body of water known as the Golfo de Penas, or Gulf of Sorrows. Around the middle of May 1741, about eight months after it left England, the Wager ran upon “two great rocks” and was wrecked.

Read more: Seagrass, protector of shipwrecks and buried treasure

The work of seagoing

Grann, a staff writer for The New Yorker, is a careful and elegant delineator of nautical labour, or what the literary scholar Margaret Cohen has described as the maritime “theater of craft.” Early on, an account of the midshipman John Byron’s hundred-foot (30 metre) ascent up the Wager’s mainmast achieves a balance of detail and drama that is genuinely exhilarating. (In a recent interview, Grann cited David McCullough’s history of the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge as a model of engaging technical prose.)

Throughout, Grann’s book registers profound respect for the work of seagoing – work Anson’s crews carried out amidst a wartime atmosphere of “constant stress.” As the Wager wrecked, its men embarked upon a new – and yet harsher – enterprise: to remain united and alive in a situation their knowledge and experience seemed helpless to comprehend.

It was wintertime on a small, mountainous island – itself called Wager, nowadays – at close to 48 degrees southern latitude. (For comparison, Tasmania’s capital, Hobart, sits at approximately the 43rd parallel south.) Between Portsmouth and Patagonia, more than one third of the ship’s complement of 250 men had been buried at sea.

Those who survived to become castaways contended with a lack of provisions and shelter and an environment they did not understand. The old social orders were cast aside. Some of these difficulties were assuaged, temporarily, through the salvage of the Wager itself.

Read more: The politics of the castaway story

Grann memorably evokes the excavation of food, alcohol, and other supplies by men who “burrowed through layers of debris, like ship-worms eating through a hull.”

With the Wager violently “decommissioned,” former crewmen felt the bonds of naval status and authority begin to loosen. Who held power at Wager Island? And by what right? Bereft of the ship, did these men even remain sailors, legally speaking?

For the Wager castaways, these perplexities soon became matters of life and death. For Grann, they impel an increasingly tense narrative of political negotiation, usurpation, and retaliation, played out against a backdrop of freezing temperatures and starvation.

Along with Byron, our cast of characters includes the Wager’s captain, the vain Scotsman David Cheap; the truculent boatswain John King; and a pious gunner – and, in Grann’s estimation, precocious writer – named John Bulkeley. They and the rest of the company were pushed, during the weeks and months they spent marooned in the Guayaneco Archipelago, to “extremities” so insupportable that many old loyalties and hierarchies were sundered.

What ensued was a drama of murder, insurrection, and escape this reviewer is loathe to reveal. It is no spoiler, however, to observe that what arises from Grann’s story is a keen concern for the contested power of stories to establish facts, construe responsibility, and give shape to the past.

Legal burlesque

Narratives bequeathed by historical mariners, such as those of buccaneer Francis Drake, furnished 18th-century navigators with (more or less dependable) information while inspiring the likes of Byron to go to sea.

Meanwhile, the British Admiralty came to require its officers to maintain detailed records of nautical incidents. A logbook account of a significant event – a shipwreck, say, and what followed in its wake – could have far-reaching consequences for the laying of credit and blame.

During and after their Wager Island ordeal, Grann’s castaways struggled for control over stories that might determine their standing, before the nation as well as the naval court-martial, should they ever make it back to England.

Among the strangest and most effective passages in this book are episodes of legal burlesque, wherein little bands of shipwrecked sailors, clad in rags and emaciated from hunger, draw up quasi-formal documents purporting to attest to some version of their experience.

Indeed, for all his wooden warships, wild seas, and remote isles, what Grann’s readers may find most extraordinary about the history he tells is the persistence, in extremis, of these vestiges of officialdom. What kept them in play, seemingly, was a vague but (for some) still-potent ambience of system and rule, along with a widely felt imperative to cultivate and defend an “unassailable story” of one’s own part in the saga.

If the spectre of a military trial – and the terror of military punishment – hung over the survivors, so did the relatively novel idea that they would soon be judged on in print and in the court of public opinion. Mid-18th century England was a time of expanding literacy, diminishing censorship, and a burgeoning popular press.

The ship chaplain Richard Walter’s authorised account of Anson’s voyage, published in 1748, became a colossal popular success and a turning-point in the literary tradition of the maritime expedition. It went on to find devoted readers in philosophers Rousseau and Montesquieu, naval explorer Captain James Cook, and naturalist and scientist Charles Darwin.

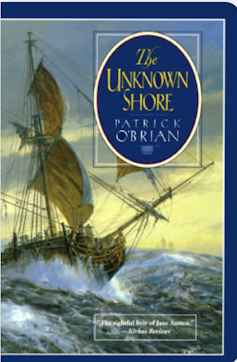

Writer Herman Melville lauded the Wager catastrophe as a “remarkable and most interesting” affair. Patrick O'Brian based an early novel, The Unknown Shore (1959), upon it. Grann and his audience are thus part of a long and prolific line of interpreters aiming to make sense of this wreck and its remains.

Understanding this wreck impinges directly upon our sense of the British Empire and the civilisation it claimed to convey. At Wager Island, Grann observes, some “supposed apostles of the Enlightenment” were reduced to “a Hobbesian state of depravity”.

At the same time, representatives of the region’s Indigenous cultures appear on the peripheries. Grann’s regard for such persons, who notably include the Kawésqar and Chono, is hazy but basically admiring. He sees them negotiating the lands and waters they inhabit with a degree of know-how the British strain even to imagine.

“Their agility in diving,” wrote Bulkeley of some Kawésqar women, “will be thought impossible by persons who have not been eyewitnesses.” The same seas that had ruined the Wager’s interloping ambitions could hardly have seemed more hospitable to the locals.

In the author’s note opening his history, Grann explains that he has “tried to present all sides, leaving it to you to render the ultimate verdict” upon the machinations of the Wager’s broken crew.

This appeal to the reader’s judgement points up the troubling, shifty nature of historical testimony, underscoring the importance of renewing our attention to the circumstances of empire’s disasters, as well as its triumphs.