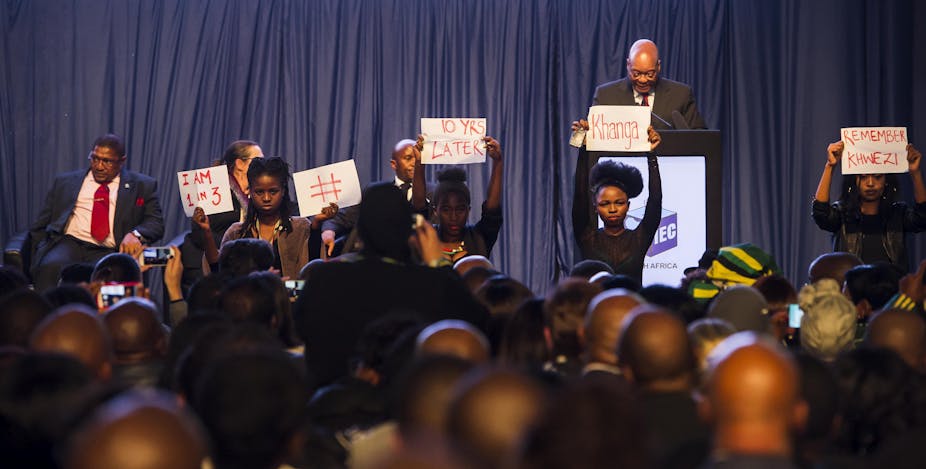

In the wake of the protest by four women at the announcement of South Africa’s municipal elections results on August 6, the details of the rape trial of President Jacob Zuma in 2006 once again come to the fore.

In the past few days, social media and the Twitterati have been ablaze with discussion about the issue. It seems that, a decade on, the meaning of this significant event will not go away.

An argument can be made that Zuma will never be able to escape its relevance and consequences. It is like the concept of original sin that requires cleansing. What a pity that the peaceful protesters in support of “Khwezi” – the name given to Zuma’s accuser – were deemed a “security threat” and forcibly removed by security men.

The ghost of Khwezi continues to haunt Zuma just as the spectre of rape continues to haunt South Africa. Even though he was acquitted, this matter will not go away. An acquittal did not erase profound concerns about Zuma’s ethics and his demeaning attitudes towards women.

Despite the judge interpreting the evidence very narrowly and devoid of any feminist consciousness, he did call Zuma’s conduct into question:

It is totally unacceptable that a man should have unprotected sex with any person other than his regular partner and definitely not with a person who to his knowledge is HIV positive. I do not even want to comment on the effect of a shower after having had unprotected sex.

Zuma claimed during the trial that he taken a shower to shield himself from infection after what he said was consensual sex with his accuser, who was HIV positive.

South Africa’s rape scourge

South Africa celebrates National Women’s Day this month to commemorate the 1956 march of 20,000 women on the Union Buildings in Pretoria to petition against the country’s pass laws. These restricted the movement of black people during apartheid, and the march was prompted by the government’s extension of the laws to women.

South Africans should think hard about how far they have come to stamp out the political, economic and cultural reasons that stand in the way of women’s progress today. And, given the country’s high incidence of rape, this reflection should include examining reasons for the high levels of violence against women.

As Dee Smythe notes in her book, “Rape Unresolved: Victims and Police Responses in South Africa”,

more than 1,000 women are raped in South Africa every day.

The ANC’s guilt

What a pity that some of those who persecuted Khwezi were members of the African National Congress (ANC) Youth League and the ANC’s Women’s League. Julius Malema, then President of the ANC Youth League, suggested that Khwezi had enjoyed sex with Zuma. The Women’s League members also mocked her.

Following the recent outcry over the treatment of the women demonstrating at Zuma’s post-election speech, the ANC, and particularly its Women’s League, has persistently argued that the resurfacing of the rape trial is an attempt to embarrass Zuma.

Even though Zuma was acquitted of the rape charges, a reading of the case suggests a man devoid of compassion and understanding when it comes to women. He is certainly not the figure to lead South Africa as it tries to deal with the continuing plague of violence against women.

Yes, this case is old and buried and the country needs to move on. Unfortunately, for the many victims of rape, it is not so easy. Their lives have been devastated and many remain imprisoned by their trauma and pain.

What a pity that Khwezi was treated with contempt and persecuted because she dared lodge a complaint against Zuma. What a pity that her sexual history became more significant than Zuma’s conduct. What a pity that, after the acquittal, she had to go into exile in the Netherlands for her own safety.

Just as democratic South Africa’s first President Nelson Mandela moved the country towards healing, so too should Zuma on the issue of sexual violence. He needs to help affirm, console and help survivors move on and begin to live meaningful lives. But, on all the evidence, he is not that person and cannot be. His record is too tarnished. Khwezi continues to be that reminder.