On the morning of Sept. 29, a packed New Jersey Transit commuter train crashed into the Hoboken Terminal where other commuters were waiting at the platform at the busy transit hub. Initial reports indicate that at least one person has been killed and over 100 injured.

Sadly, but also tellingly, the majority of the following paragraphs comes verbatim from a previous article I was asked to write on Positive Train Control (PTC) following the Amtrak 188 crash where, on May 12, 2015, northbound Amtrak Northeast Regional Train 188 carrying 238 passengers to New York from Washington, D.C. derailed near Philadelphia. In that accident, eight people were killed and more than 200 injured when the train entered a curve at almost twice the designated speed limit. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined that the train engineer lost situation awareness and that PTC could have prevented the accident.

Similar to the Amtrak accident, the NJ Transit train engineer survived, and the NTSB will surely investigate the accident. While it will be a long time before the exact cause of the Hoboken accident is determined, it seems that PTC could have again prevented the loss of lives, injuries, and chaos on Sept. 29.

Therefore, there are serious questions about why the technology has not been implemented on these trains and tracks despite an ongoing federal mandate and when, at the same time, companies are developing, testing and operating much more sophisticated and effective technology in autonomous vehicles traveling on city streets.

Crash behind the mandate

Positive train control (PTC) may have been able to prevent this accident, and it is not the first time this sentiment has been echoed. In 2008 a similar accident prompted federal action. I coauthored a study on PTC for Congress in 2012.

On Sept. 12, 2008, a passenger train collided with a freight train, resulting in 25 fatalities and 135 injuries in California. The engineer of the passenger train was distracted due to texting, and the NTSB specifically stated that PTC could have prevented this accident.

Within a month the Railroad Safety Improvement Act of 2008 (RSIA08) became law and mandated that PTC must be implemented on about 60,000 miles of track “providing regularly scheduled intercity or commuter passenger transportation” by the end of 2015. The abnormally fast response can be attributed to support from Sen. Barbara Boxer of California, who was the chairman of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works at the time.

The federal government granted an extension for some railroads, including New Jersey Transit, until 2018. Unfortunately, the recent accident came before that deadline, and none of the New Jersey Transit lines have PTC.

While implementation of PTC is moving forward in some places, system-wide implementation continues to face significant barriers due to high costs, interoperability requirements and communication spectrum availability.

What is Positive Train Control?

PTC from a functional perspective is a system designed to prevent train-to-train collisions, over-speed derailments, incursions into established work zone limits, and the movement of a train through a switch left in the wrong position.

The technical aspects of these systems can vary but generally include a positioning system on each train, information on movement authorities on sections of track (e.g., speed restrictions) and a way of communicating these data throughout the network. For example, PTC would override manual control if it sensed that the train was entering a section of track at double the posted speed limit.

Interest in PTC dates back to at least 1990, when the NTSB first placed it on its “Most Wanted List of Transportation Safety Improvements,” where it is still regularly featured up to the most recent list in 2015.

The FRA estimated that between 1987 and 1997 an annual average of seven fatalities, 55 injuries, 150 evacuations and over US$20 million in property damage could have been prevented by PTC. To put this in the context of the entire transportation network, there were 33,782 fatalities on the road network in 2012.

Although PTC is on NTSB’s “Most Wanted List” and many serious incidents due to human error could be prevented, the monetized safety benefits are significantly less than the costs. The FRA estimates the annual monetary value of the safety benefits from PTC to be about $90 million. The safety benefits may be slightly larger today considering several serious accidents stemming from a boom in oil shipped via rail.

The costs

The law is an unfunded mandate, which means the costs of meeting the requirements are borne by the railroad operators. The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) estimates that the total capital cost for full PTC deployment according to law would be about $10 billion (about one year’s worth of capital investments for the major U.S. railroads) and annual maintenance costs of $850 million.

While this investment might be feasible for major U.S. freight rail companies, local and state governments with tight budgets will have a much more difficult time allocating funds for PTC. This could be a huge issue and reason that the New Jersey Transit does not currently have any PTC systems. The infrastructure cost alone for just two of the five largest transit agencies operating on the corridor, Metro-North in the New York area and the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority in the Philadelphia area, is estimated at $350 million and $100 million, respectively. Commuter railroads’ cost for installing PTC is likely to be borne primarily by state or local governments.

The FRA established an annual $50 million grant program to help support the development of PTC, but the grant has been funded by Congress for only $3 million – well short of the total required cost of $2.75 billion estimated by the American Public Transportation Association.

Regardless of the federal mandate and possible future benefits, the costs of implementing PTC is cited as a significant barrier.

The systems integration barriers

In addition to costs, PTC has faced barriers in technical implementation, namely system interoperability, and allocation of communication spectrum.

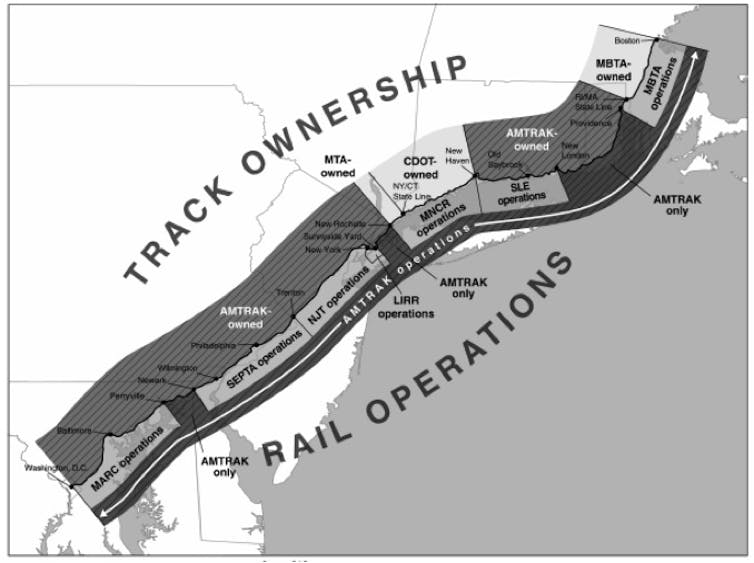

Interoperability is key in successful implementation of PTC. For example, in the case of the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak operates on both Amtrak owned-track as well as track owned by regional transit authorities and vice versa. Elsewhere, Amtrak operates on track owned by freight railroads. It is necessary to ensure that the systems developed by the freight railroads, Amtrak, and regional authorities all communicate with one another. While interoperable systems have been developed, some issues persist.

Another system integration issue is the acquisition of radio spectrum to support the communication demands of PTC. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) generally holds auctions for spectrum, but allocates some for emergency services and government agencies. However, the FCC so far has not addressed the needs of PTC.

A consortium of railroad companies exists to purchase appropriate spectrum, but the amount of spectrum and frequency are still uncertain - especially in highly congested areas in major cities where choices in spectrum may be scarce. Without guidance from the FCC, obtaining spectrum and ensuring its interoperability is time-consuming and costly.

Going forward

It remains to be seen whether Congress will take immediate action following the New Jersey Transit accident as it did with the 2008 accident in California.

Congress did little in response to the Amtrak incident. For instance, a bill was introduced in the Senate in March of 2015 to extend the PTC deadline to 2020 to help accommodate the cost, interoperability and spectrum barriers the railroads are facing. A year and a half after S. 650 was introduced, it was placed on the Senate legislative calendar. The future of the federal PTC mandate is unclear.

It is also worth mentioning that the original PTC legislation was passed in 2008. Perhaps at that time the concerns about technology and cost had some merit; however, there is ample room for skepticism on the estimates today. Since 2008, companies like Google, Uber and others have developed, tested and currently operate autonomous vehicles on American roads where complexity far exceeds a train on a fixed track. There are obvious differences in terms of these companies and government-funded transit programs, but arguments centered on cost and complexity are beginning to sound much more like gripping and foot-dragging than legitimate concerns.

This article is an updated version of one that originally ran on May 15, 2015.