Stalin’s terror and purges of the 1930s discouraged any Soviet official from putting a pen to paper, let alone keep a personal diary. The sole exception is the extraordinarily rich journal kept by Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador to London between 1932 and 1943, which I unearthed in the archives of the Russian Foreign Ministry in Moscow.

No personal document of such breadth, value and size has ever emerged from the Soviet archives. For the last decade I have scrupulously edited and checked the diary against a vast range of Russian and Western archival material as well as personal papers to allow the wider public access to this remarkable relic.

At the epicentre of the dramatic events leading to World War II, Maisky was possessed with a passion to leave behind his own account. The unique diary reveals in a lively, candid and accessible way how then, just as now, mutual suspicion, preconceived ideas and the legacy of the past blinded both British and Russian politicians and brought the world to the brink of catastrophe.

The diary tells an exceptional story of a brilliant Soviet diplomat, who despite the looming danger of being recalled any day to Moscow and shot like most of his colleagues posted in other European capitals, diligently sought to harmonise Soviet and British interests. The result is absolutely mesmerising.

Hailed by Paul Kennedy as “perhaps the greatest political diary of the 20th century”, Maisky’s diary is a treasure trove of a vast array of topics. It reveals the degree to which Russia was left out in the cold during the 1938 Munich Agreement and how it might have been possible to prevent the Russians from signing the neutrality pact with Nazi Germany in 1939. It exposes that if the alliance that was forged between Great Britain and the Soviet Union in July 1941 had been in place two years earlier, World War II might have been averted.

As historian Niall Ferguson suggests, Maisky’s diary exposes the missed opportunities “to sup with the diabolical Stalin in the 1930s” and the dire consequences of doing so, halfheartedly, after the German invasion of Russia in June 1941. This late attempt was responsible for the shaky postwar arrangements and the outbreak of the Cold War.

Political plotting

The immediate impression conveyed by the diary is the pivotal role of the human factor, transcending controversies over policy and ideology. It reveals the immense impact of personal friendships, conflicts and rivalries within the Kremlin as the main factor in the formulation of Soviet foreign policy. For example, the rivalry between Molotov, the Soviet minister for foreign affairs, with his predecessor Litvinov finally led to the withdrawal of Litvinov’s protégé, Maisky, from London in 1943 and the two years he spent in prison after Stalin’s death.

Maisky’s unconventional style of diplomacy, which at the time irritated many of his interlocutors, was revolutionary. It has since become the norm. He was certainly the first ambassador to systematically manipulate and mould public opinion, mostly through the press. What an ambassador has to aim at, Maisky told his friend Beatrice Webb:

… is intimate relations with all the livewires in the country to which he is accredited – among all parties or circles of influential opinion, instead of shutting himself up with the other diplomatists and the inner governing circle – whether royal or otherwise.

A superb PR man at a time when the concept hardly existed, Maisky did not shy away from aligning himself with opposition groups, backbenchers, newspaper editors, trade unionists, writers, artists and intellectuals. He colluded with the opposition of Churchill, Eden – Beaverbrook and Lloyd George – seeking to sway Chamberlain from appeasing Hitler towards an alliance with the Soviet Union.

The diary further reveals how, following the German invasion of Russia and with Churchill now in the saddle, Maisky unhesitatingly exploited the pro-Soviet feelings in London to create a momentous public movement in favour of a second front, plotting with Eden and Beaverbrook against the prime minister, for his rejection of the cross channel offensive. “We are in a jam over this second front business,” confessed Eden, “we have to try to ‘bluff’ the Germans; to do so we must deceive our friends at the same time.”

An insider’s account

Especially gripping are Maisky’s descriptions, as an informed outsider, of London during the Blitz:

If bombs start exploding in very close proximity, we move to the ‘shelter’. Agniya and I have a special room down below, where we live like students. At night we sleep in the shelter, which is relatively safe, and hear neither the bombs nor the antiaircraft batteries. We sleep like soldiers, of course, dressed or half-dressed. The duty officer wakes us at 5 or 6 a.m., once the ‘all clear’ has sounded, and all of us – sleepy and dishevelled – return home to sleep in our own beds for the remaining three or four hours. That’s how we live. It’s more or less tolerable (leaving aside the squabbles among the staff over places in the shelter). But can one live like this for long?

Equally fascinating are his frequent intimate meetings with Churchill and Eden during the war. The very intimacy Maisky enjoyed with the top echelons of British politicians and officials, as well as with intellectuals and artists, gave him a perfect vantage point. His intimate interlocutors included five British prime ministers – Lloyd George, Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill – as well as monarchs: King George V, Edward VIII and King George VI.

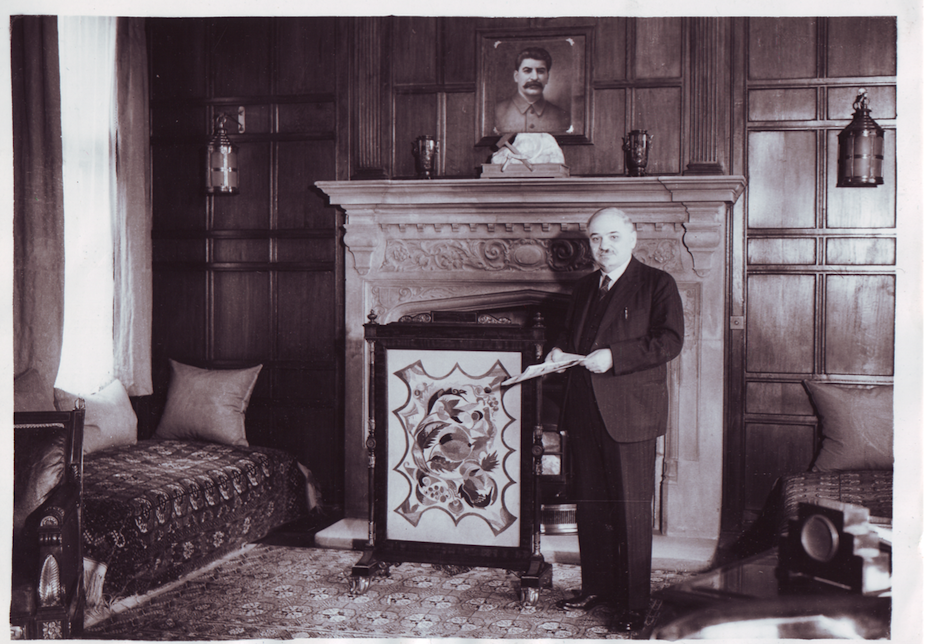

His circle of friends also included intellectuals and writers such as Bernard Shaw, H G Wells, the controversial modernist artist Epstein (who sculpted his bust) and the painter Kokoschka, who executed an intriguing portrait of him. With Russia allied with Britain after 1942 Maisky became the most popular and sought after foreigner in London. Fascinating accounts of his activities with these influential people fill the pages of his diary.

The significance of his war reminiscences can hardly be overstated. While it was the practice of the foreign secretary to keep a record of his meetings with ambassadors, this did not apply to the prime ministers. No records are therefore to be found in the British archives of the many crucial conversations held between Maisky and Churchill before and during World War II.

Yet the diaries describe an exceptional intimacy which existed between Maisky, Eden and Churchill and their families. At times it even led to “heaps of cipher telegrams” which were shared with him in Whitehall. The diary thus becomes an indispensable source, replacing the retrospective accounts – tendentious and incomplete – which have misled historians on many fronts so far. It would hardly be an exaggeration to suggest that the diary rewrites history which we thought we knew.

A cosmopolitan, polyglot, independent-minded and former Menshevik, Maisky was in a particularly vulnerable position. Churchill’s praise of him as a first-rate ambassador drew from Stalin the snippy comment that “he talked too much and can’t keep a still tongue in his mouth”. Maisky succeeded nonetheless in maintaining the delicate balance until his arrest, in 1953, at the age of 70. Accused of treason, having “lost his feelings for the motherland”, he was saved by the bell when Stalin died two weeks later.

The Maisky Diaries: Red Ambassador to the Court of St James’s, 1932-1943, edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky, is published by Yale University Press.