For most of the world’s population, the end of the second world war was a glorious day. This was not necessarily the case for Japanese-Australians, who faced repatriation to Japan after being interned by their home country, Australia.

Shortly after Japan entered the war in December 1941, 1,141 Japanese people living in Australia were seized and transferred to “enemy” camps – accounting for 98% of the total Japanese population in Australia. This was much higher than the proportion of Italians and Germans sent to Australian internment camps.

At the camps, such as those located in Loveday in South Australia, Tatura in Victoria and Hay and Cowra in New South Wales, Japanese internees were treated by Australian guards according to the Geneva Convention. But there was little contemporary Australian press coverage of these camps, and many Australians did not know about them – even if they lived locally.

In my newly published research, I have been exploring the forgotten experiences of Japanese-Australians during the second world war.

Read more: The overlooked story of the incarceration of Japanese Americans from Hawaii during World War II

The Cowra breakout

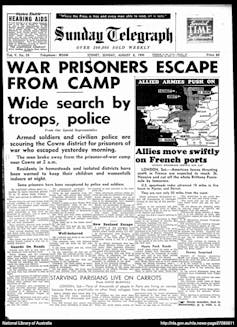

One of the only pieces of contemporary news reporting on the internment of Japanese people followed the Cowra breakout in August 1944, when captured prisoners of war tried to escape. Four Australians and 231 Japanese soldiers were killed.

Even after the war, most of the media coverage focused on these POWs rather than the interred Australian residents.

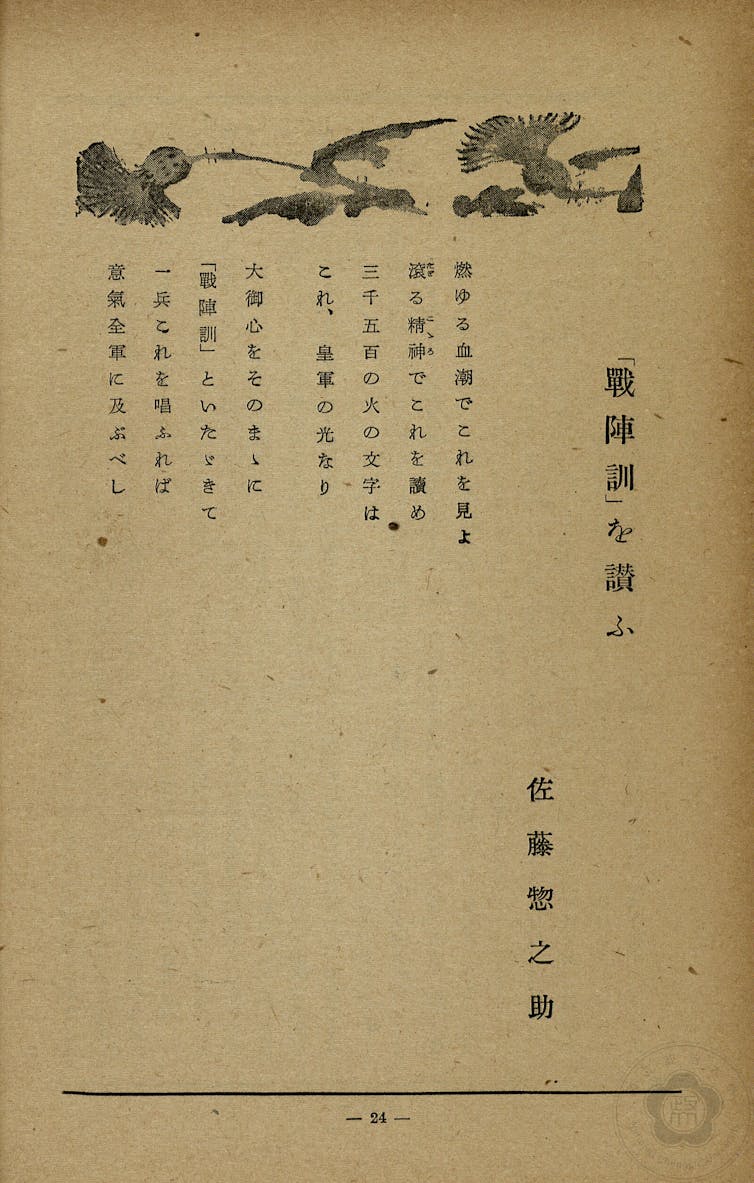

Japanese POWs followed the Senjinkun military code, by which “a soldier was expected not to survive to suffer the dishonour of capture”.

This was encouraged by cultural critiques, artists and poets, exemplified by a surviving poem by Sonosuke Sato. Japanese soldiers were brainwashed to believe the chance to die was an honour.

Common to Australian media publications on this breakout is a tendency to treat the Japanese as “others”. A clear distinction exists between “us” and “them”. It was difficult for Australians to understand the motives of the fatal military decision to escape the camp where they had been treated humanely.

In contrast, media reports did not mention the experiences of the civilian Japanese living in Australia and therefore free from the Japanese military mindset.

Japanese-Australians

In pre-war Australia, many Japanese-Australians were working as pearl divers. There were also a hundred or so Japanese elites working for banks and trading companies in Sydney and Melbourne.

Many Japanese had departed Australia in the 1930s when an unofficial trade war erupted between Australia and Japan. More left as the threat of war grew and Japanese residents faced increasing discrimination and fewer business opportunities.

Not every Australian with a Japanese background associated themselves with the community, or identified strongly with their heritage. But when Japan joined the war, Australia captured the “Japanese”, even those who had lived in the country for decades or were born in Australia.

They were joined in camps by Japanese people shipped from nearby allied territories such as New Zealand, the Pacific and Indonesia.

One of them was Cairns-born Samuel Nakashiba, raised as an Australian without Japanese language fluency. Nevertheless, he was captured and imprisoned as “Japanese”.

Nakashiba lodged his first application for release in June 1942. He was not released until May 1945, when the relevant authority found a job for him in an isolated place in Queensland.

Yet Nakashiba was still lucky. He was one of only around 200 Japanese permitted to remain in Australia after the war. The rest were deported to Japan, even those with no or few ties to the country.

Repatriation to Japan

Hikotaro Wada, a laundryman, was arrested in Kalgoorlie in December 1941.

Arriving in Australia in 1891 when he was 21, he briefly visited Japan in the 1920s, when he discovered he had no family left there and immediately came back.

He applied for release during the war but was unsuccessful. He was sent back to Japan in 1946 after having lived in Australia for 50 years. His fate after repatriation is unknown.

Shigeru Yamaguchi, born in Broome, was listed as “Australian-born Japanese” in the official camp record. He stayed in the camp until the end of war and was then repatriated to Japan.

Prior to his arrest in January 1942, Yamaguchi had made a life as the owner of a vegetable garden in Geraldton, Western Australia. After the war, a major at Loveday camp “advised” him to leave for Japan, believing his prospects would be better there.

In 1947, while serving as an interpreter for the Allied Forces in Tokyo, Yamaguchi requested a re-entry permit to Australia. He was not granted permission to return. His fate after 1947 is also unknown.

In the 1950s, some Japanese divers who had worked in pre-war Broome returned to Australia. As a farmer, Yamaguchi was unlikely to have been in this party. My research on Yamaguchi ended here; Japan has highly restrictive privacy laws that block access to official individual records by anyone other than direct offspring.

Read more: 300 letters of outrage from Japanese Canadians who lost their homes

The American redress movement

During the United States’ involvement in the war, 112,000 “Japanese” were placed in internment camps. Some chose to move to Japan after the ill treatment by the US government.

Japanese-Americans began the redress movement in the 1960s. President Ronald Reagan signed an act to grant reparations for the internment of Japanese-Americans in 1988. In 1991, President George Bush senior stated: “The internment of Americans of Japanese ancestry was a great injustice, and it will never be repeated.”

By contrast, in Australia no apology has been made to the “Japanese” people who were captured or repatriated, even when Australia was their home.

In the same way stories of diggers and soldiers are Australian stories, experiences of the Japanese-Australians who were unfairly labelled as enemy aliens at our own internment camps should also be regarded as Australian stories.

Have we listened to their stories? And can we say sorry?